War Comics:

Reinforcing The Military's Propaganda Machine?

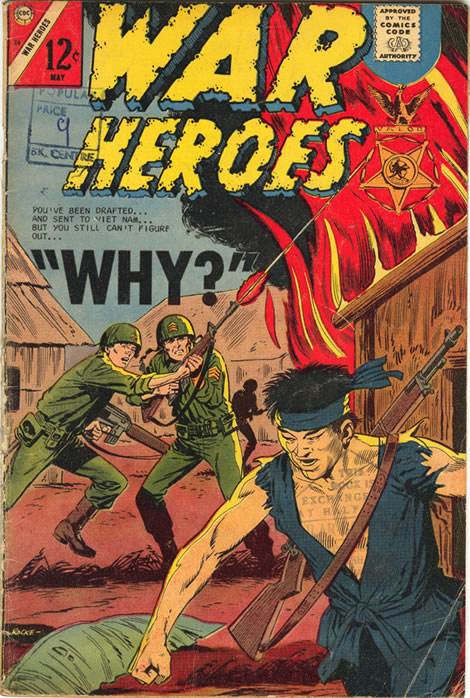

‘You’ve been drafted… and sent to Viet Nam… but you still can’t figure out…“WHY?”’ A lot of people are wondering “WHY?” today as parallels become increasingly clear between the wars in Vietnam and Afghanistan. Maybe it was this nagging question, and all the recent losses of British troops and pageantry over Armed Forces Day here in Britain and Obama’s sacking of General McChrystal, but something made this cover of War Heroes No. 24 drawn by Rocco ‘Rocke’ Mastroserio catch my eye. I found this Sixties American comic book in the bargain back-issues box last weekend, its cover liberally stamped with a Popular Book Centre price box, for nine old pennies in blue biro, and the diamond-shaped Half-Price Exchange tattooed onto the Viet Cong’s bare chest. Let’s take a closer look.

Here’s a young U.S. recruit deflecting his sergeant’s gun, stopping him from shooting a fleeing Viet Cong enemy and apparently calling into question the whole rationale of the conflict itself. Here’s a mass-market war comic book published by Charlton Comics in May 1967, at the very time that the Vietnam War was being waged amid growing anti-war demonstrations at home. It is remarkable that such a war comic would dare to address such burning, topical issues. War comics today as a cheap newsstand genre have all but vanished on both sides of the Atlantic, and of those that survive, notably the pocket-sIzed Commando Picture Libraries still coming out from D.C. Thomson’s, Dundee, it’s hard to imagine any that would dare to deal with the equivalent concerns of say soldiers currently fighting in Afghanistan or any hint of objections to the war itself. Let’s stick to old wars, especially World Word Two, the ‘just war’ which the Brits, of course, won.

So I was intrigued to see how this story, ‘Why?’, played out inside. Notoriously, dramatic cover images designed to grab your attention and cash end up not being the same once you look within, but more or less the same scene forms the splash of the final eight-page story pencilled by the workhorse partnership of penciller Charles Nicholas and inker Vince Alascia. The writer is uncredited but could be the prolific Joe Gill or even Willi Franz, author of The Lonely War of Willy Schultz. I’ve scanned the whole story below, just click to enlarge the pages:

Our first-person narrator is the naive young Pvt Walt Andrews, who flunked out of junior college and got drafted to the ‘Nam. When he spots his first V.C. (Viet Cong) and prevents Sgt Ludden from nailing him, Ludden punches Andrew and threatens, ‘Next time you pull a thing like that, you get the bullet, Andrews!’ The lengthy intro caption explains Andrews’ pacifist misgivings and his confusion caused by letters from his friends back home who describe the Viet Cong as freedom fighters, ‘just as our ancestors were in the Revolutionary War.’ Who should he believe?

On page two, when Andrews disobeys orders to throw a grenade first into a hut and steps inside, he freezes in fear as he faces the armed enemy and, failing to pull the trigger, lets him escape. It’s at this point that Andrews is forced by the sergeant to see for himself how the village headman and his family have been slaughtered by the enemy. Ludden growls, ‘You can write home to the bleedin’ hearts and tell them how the Viet Cong fight a war!’ As one aghast soldier walks out of the headman’s hut, eyes wide, hand to his head, able to voice only an ‘Aaaaarrrrgghh…’, Andrews steps in and witnesses the horror first-hand, out-of—shot and left to our imagination. Something of a turning point, this massacre seems to convince him that what he thought was merely propaganda about the evils of the Viet Cong is ‘sickeningly real’.

Equally important in firming Andrews’ resolve is the next scene where he is able to look after the women and children survivors, and ‘feed them candy and earn their trust’. As the drama unfolds, Andrews completes the cycle by spotting and injuring ‘the one who got away’, who is none other than the ‘leader of the gang that terrorized these people’, and finally by being the soldier to shoot him dead. His change of attitude runs parallel to this, for example in a three-panel interlude showing Andrews, flat-coloured in pale purple, as he muses about his fellow soldiers’ lack of ‘any doubts about whether or not they’re on the right side.’ The seventh page opens with a surprising inset thought balloon as Andrews pictures his ‘buddies… back home’, his girlfriend and his friend, Larry Lustig (a suspect German surname), brandishing their anti-war, pro-Viet Cong placards. Gritting his teeth, eyes narrowed and steely, Andrews has turned a corner and seems to have no qualms about taking his first life. The story’s conclusion shows a smiling Vietnamese kid, chomped candy bar in his hand, asking Andrews what he is writing home. All doubts now erased, Andrews is severing his relationship to his girl and buddie [sic] and wants nothing more of ‘their kind of letters from home.’ Andrews now knows ‘Why?’ this war is being fought and so do we, the readers.

It’s a fascinating piece of quite clever propaganda, contemporary to the conflict itself and confronting and countering complaints being raised against it. One surprise is that the dreaded ‘C’ word Communism is not mentioned once. It should come as no surprise that this story does not finally contradict the official pro-War party line; the book is titled, after all, War Heroes, and has the Valor medal as part of its logo. Nevertheless, it must have touched some nerves among those serving soldiers and those facing the draft at home who would doubtless have read it. Some perhaps would have seen themselves in the troubled Walt Andrews. Tellingly, there’s a statement of ownership filed inside which shows that the latest single issue to filing date had a total net press run of 234,500 copies, of which 126,900 sold off the newsstands, including via Army Pxs, and a meagre 19 sold on subscription. There were plenty of much better-selling Sixties comic books than War Heroes, but by today’s standards in the U.S., those are mightily impressive sales, albeit at only twelve cents an issue, and would make this title an absolute top-seller today. Aside from hyped events, regular monthlies sell only a fraction and mostly through specialist comic shops, eg Batman 61,157, or Superman 33,336, or Unknown Soldier, one of the only current war-related titles and quite impressively done, which manages to shift only 5,611. Of course, some of this same material can now live on to sell better and for longer once compiled into trade paperbacks. All the more surprising then, that within another three issues, Charlton would suspend War Heroes with No. 27 in November 1967.

Cheap and cheerful Charlton Comics are among the most shoddily produced comic books, lending them a sort of odd charm. This copy has some diabolical printing, on presses otherwise used, it seems, to churn out breakfast cereal packets, including large blobs of black ink spattering the inside gutters on two pages, while copy proofing is lax, misspelling Andrews as Andres and buddy as buddie. There’s also an advert in this issue for the June 1967 issue of Army War Heroes, No. 19, with a World War Two cover-story entitled ‘Mama’s Boy’ dealing with cowardice. An officer shouts, ‘Come on, Ludden! You gotta fight now… cry later.’ Could this be the same trooper who rises through the ranks to becomes Sgt. Ludden by 1967 in ‘Why?’.

Around this period, Charlton made a point of adding timely tales tackling the Vietnam War and reflecting some of the moods of the forces on the ground, naturally without ever extolling desertion, draft-dodging or the inhumanity of war itself. Several of these stories were promoted on the front covers, such as: Army War Heroes No. 27, October 1968: ‘Wet, bug-bitten, sick, and tired… no wonder they called it… “This Crummy War!”’ ; or Fightin’ Army No. 66, January 1966, whose eloquent G.I., standing in the burning rubble of a village, with a little Vietnamese boy clutching his leg, declares: ‘Go ahead son… cry… your family, your village… wiped out by the “Cong”. If we hadn’t arrived when we did, they’d have gotten you, too! I wish all those who call us…whatever they do… I wish they could talk to me! I’d tell them why we’re here!’

It’s no coincidence that around this time, Fightin’ Marines (note the slang dropping off of the ‘g’, which Charlton also prefixed onto the Army, Air Force and Navy) introduced the much-more gung-ho, all-guns-blazing Sgt ‘Shotgun’ Harker and Pvt ‘Chicken’ Smith as an ongoing heroic twosome in Vietnam, cover-featured on No. 78, January 1968. The counter-arguments against the war would find expression in comics elsewhere, at their most shocking in Tom Veitch and Greg Irons’ nightmarish indictment, the 1971 underground comic Legion of Charlies. To read this, see the reprint in David Kendall’s excellent 2007 compendium, The Mammoth Book of Best War Comics.

As for that Charlton title War Heroes, curiously it was revived, though in name only, by Mark Millar and Tony Harris in 2008 for a six-issue mini-series from Image. Unlike the relative realism and grounded grittiness of Charlton’s Vietnam-era grunts, today’s War Heroes enter the fray enhanced with super powers like Captain America, but so far devoid of much in the way of doubt, conscience or character. Is anybody here going to ask ‘Why?’ Rather than deal with the complex present-day, Millar speculates on the future War on Terror escalating in Iran. Millar may pose a few soft questions en route, but his self-confessed main thrust is to deliver a ‘romp first and foremost.’ Or as blogger Bob Mitchell summed it up succinctly: “an NRA wank-fantasy where the individual becomes a living weapon.”

After much self-publicity hyping that this War Heroes was Hollywood-bound and Sony-optioned, it’s all fallen rather limp with the last three comics still to be completed and the movie stalled. Maybe its coolness has already passed. This flashy War Heroes is a universe away from Charlton’s humble journeyman newsprint anthology. The war hero in ‘Why?’ is an ordinary, vulnerable young man, not like the toy soldiers advertised by Lucky Products Inc. on its back cover ‘made of durable plastic, each with its own base’. At least Charlton’s War Heroes were not afraid occasionally to acknowledge directly some of the actual concerns of their times and their readers, even if they ultimately tended to reinforce the military’s propaganda machine. I’m glad I picked up this old, faded bargain comic book - it’s a time capsule of its era and a mirror reflecting onto our own.

Posted: July 4, 2010