Oscar Zarate:

A Lifelong Passion

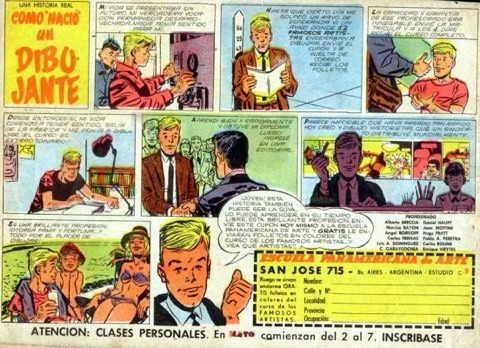

A Londoner from Argentina, Oscar Zarate’s enthusiasm for comics has shaped his life and fuelled collaborations with comics scribe extraordinaire Alan Moore and alternative comedian Alexei Sayle, and now his first solo graphic novel, The Park. In Argentina’s capital Buenos Aires in the Fifties, no youthful dreamer could resist those tantalising comic strip advertisements for the PanAmerican School of Art. The short strips claimed to be ‘a real story’ about ‘How An Artist Is Born’. It opens with a 17-year-old who supports his family by labouring in a factory, but he has a talent for drawing. Sending off for the free introduction, he is accepted into the ‘Twelve Famous Artists correspondence course. On graduation, his teachers recommend him to a magazine, where in no time he becomes a success, creating comic characters and sketching glamorous models in his studio. The last panel shows the likely lad beaming and relaxing with his pretty female companion over a poolside drink, saying “I feel really happy. This profession is marvellous, it gives me lots of satisfaction.”

A young Oscar Zarate couldn’t resist. “I saw an advert in a comic magazine for a correspondence course promising to teach working-class boys how to become successful comic artists, a way out of having to support their families with menial jobs. Fame, fortune, silk dressing gowns and beautiful women were bound to follow, and Hugo Pratt (below) was one of the teachers and Alberto Breccia too! My parents were very supportive as long as I did my homework. I was sure this course would be my passport to a rosy future. I put my heart and soul into this one year course but despite getting my diploma at the end of the year, I knew that I was nowhere near good enough. However I found out something very important - learning to draw doesn’t finish when you get your diploma. Drawing is a lifelong project.”

A lover of comics since before he could read, Zarate remembers, “My childhood was filled with images of foreign lands, funny costumes, travelling in space. I would fill those little frames with all kinds of sound and movement. I was part of the story, another protagonist, totally involved. I have always felt that comics as a language has more in common with reading or listening to the radio than watching films or TV, in that comics leave more space for one’s active imagination.” In the early 1950’s a lot of American adventure newspaper strips were translated in Argentina, and among Zarate’s favourites were Alex Raymond’s Rip Kirby, Bob Schoenke’s Laredo Crockett (below), Frank Godwin’s Rusty Riley, and Roy Crane’s Captain Easy. “To me these strips looked more accomplished than the ones produced locally, somehow the artists were better to my eyes.”

His attitude toward comics produced in Buenos Aires changed when he discovered the western comic called Sgt. Kirk (below). “It was drawn by Hugo Pratt and written by Hector G. Oesterheld. Kirk was a soldier of the Seventh Cavalry, who breaks his sword, quits the regiment and decides to live among the Red Indians. I was 11 years old and this story was completely different to what I’d been reading until then. This was subversive stuff! Sgt. Kirk completely changed my view of American comics. Hugo Pratt’s art moved me so deeply that it formed my desire to become a comic artist like him. This was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I felt I wanted to make people feel what Hugo Pratt made me feel.”

Leaving school at the age of 14 (at that time in Argentina secondary education was not compulsory), Zarate landed his first job in the industry. “I was incredibly lucky. Through a friend of a friend I got a job as an errand boy for Editorial Abril, a publisher of several weekly comic magazines and Walt Disney’s merchandise. Misterix was the most popular comic magazine selling 250,000 copies every week - of course there was no TV at that time. It contained five serialised stories which would each run for months and months, stories covering different genres - western, historical, science fiction - and one of the stories was Sgt. Kirk. One my jobs was to go to the comic artists’ homes to collect the artwork which would be published the following week. Every week I went into the houses of my gods, Hugo Pratt, Alberto Breccia, Carlos Freixas, Solano Lopez, Carlos Roume. Gradually I began to show them my drawings and I learnt a lot from their very patient comments. I was in heaven. And every month I got my salary as well.”

In 1957, the writer Hector G. Oesterheld left Abril and decided to set up his own comics publishing house, Editorial Frontera. In Zarate’s opinion, “Oesterheld was an incredible scriptwriter, he changed the landscape of how to tell stories. No matter which genre he worked in, he created excellent human characters. When they opened their mouths, you believed in them. Most of the best comic artists left Editorial Abril and joined him in his new venture. These artists knew that Oesterheld would provide them with the best stories and they would become better artists working with his scripts. I worked there too - by this time I had progressed to sticking the balloons on the frames and drawing the tails!”

During this period, however, comics were being widely criticised for corrupting youth, while other influences were distracting Zarate. “I was beginning to be exposed to other things apart from comics. I read contemporary fiction and Karl Marx and starting looking at painters like Van Gogh, Modigliani, Toulouse Lautrec and Japanese artists. I watched not only American films but the films of the Nouvelle Vague and gradually I felt my childhood dreams were being questioned. Now I thought that comics were ‘inferior’ to ‘real’ art. This was one of the most distressing times in my life, this was my first real crisis. In addition, comics were coming under attack at that time.They were seen as a bad influence on young people, pushing them into delinquency. I quit comics, or at least the idea of being a comic artist. I carried on drawing and reading comics (in the closet). I decided to get my secondary school qualifications and I began to study architecture. I did it for few years but I was never happy. In the end I quit and I began working in advertising. That was the level of my confusion - despite all my left-wing ideology I became a very successful Art Director in the Walter Thompson advertising agency. It was like trying to mix water with oil. After a whiIe I left advertising.”

Turning his back on his successful career in advertising, Zarate made the life-changing decision to leave his homeland in 1971. “I left Buenos Aires at the beginning of 1971 for a cluster of reasons, primarily because the political situation in Argentina was getting worse, the right-wing military was in power, friends were arrested and some were ‘disappeared’. It was better to leave the country, hoping that eventually everything would improve and then I could return. I travelled around Europe and arrived in London in May 1971 and it was the first European city that really surprised me. There was this alternative life close to my sensibility, a different lifestyle. People were living in communes, creating co-operatives and independent cinemas and theatres. There was even a new magazine, Time Out, which listed all the alternative events and venues. So much experimental stuff was happening everywhere in London. I loved this place and at the same time the situation in Argentina was getting worse. More people were being killed by the military and some of my friends escaped to Europe. It was no time to think of returning to Argentina. Then my son was born in London and the decision was taken for me. I stayed in London for good.”

In his quest for gainful employment, he approach British publishers with whom he shared some political empathy. “I took my portfolio to the Writers and Readers Co-Op, a publishing house created by Arnold Wesker, John Berger, Richard Appignanesi, Lisa Appignanesi and Glen Thompson. I was commissioned to illustrate Introducing Freud, written by Appignanesi. The series format was not a comic book but I tried to tell the story using comic devices. Introducing Freud (above) was my first graphic book in England. It’s been a bestseller for 35 years, translated into 24 languages.

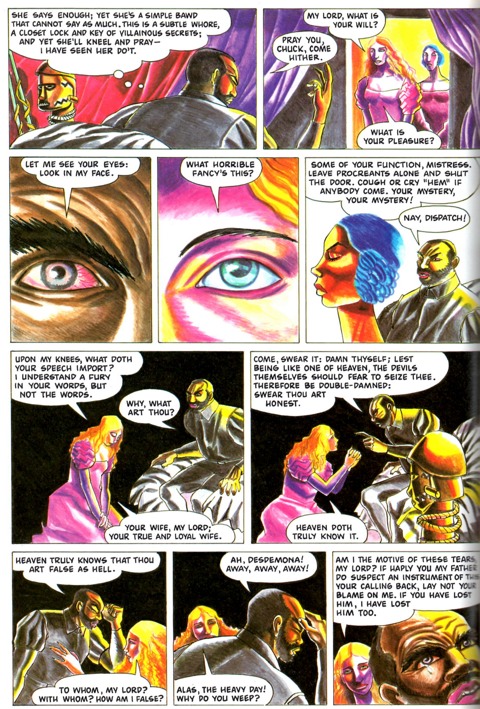

Around the late Seventies and early Eighties, England was a very difficult place to do my own comics. So I did comics adaptations of Shakespeare’s Othello with the complete text (above) for Anne Tauté‘s Oval Projects and of Marlowe’s play Dr Faustus (below), which was fun but it was not what I wanted to do in comics. I wanted to tell stories with no specific roadmap and without the protection of a genre, just to find out, page after page, what it is to be a human being. These are the stories I wanted and still want to tell, about people I can believe in, people who are telling me something and who I have to listen to.”

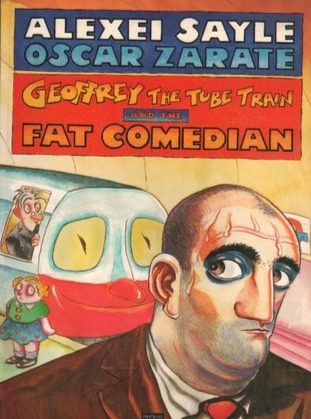

Rather than adapting another dead playwright, Zarate began seeking out living writers to collaborate with. In 1984 he contacted alternative comedian Alexei Sayle, after reading his travelogue parody Train To Hell. “I thought what he was saying in his words had to do with what I was saying in pictures. The starting point was something on London. We’d both moved here 16 years ago, Alexei from Liverpool.” Gestating the project together and responding to Thatcher’s Britain, they released Geoffrey The Tube Train And The Fat Comedian in 1987 from Methuen (below), part socio-political commentary, part Sayle’s skewed autobiography, part warped version of Thomas The Tank Engine. Zarate explains, “The book tackles serious issues. It’s not fatalistic, it’s pointing out what is going on. It’s more like a mental state than any specific topical satire.”

Next, Zarate connected with Alan Moore in 1988, post-Watchmen, while he was contributing to Moore’s anthology AARGH! (Artists Against Rampant Gay Homophobia), published by Moore’s Mad Love company to protest against Clause 28, the government’s legislation against the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality. Zarate’s initial spark - an adult pursued by a child - so intrigued Moore, that the two of them began evolving it co-operatively through a synergistic meeting of minds into A Small Killing, published by Victor Gollancz in 1991. The story concerns Timothy Hole, an advertising executive who has, as Zarate comments, “…countenanced such a big betrayal, that he loses himself. He goes back to the place he was born looking for something of what he used to be.” This allegorical, redemptive critique of callous Thatcherite values stands up as one of Moore’s most singular and significant non-genre graphic novels.

As Zarate recalled in ‘Anatomy of a Killing’, the afterword to the Avatar edition of A Small Killing, “Alan used to create superheroes and I had nothing to do with superheroes. But we shared a curiosity: He wanted to innovate, to move in some other way. After Watchmen, he wanted to talk about other things and it seems that our encounter happened at the right time. We spoke a while about what we could do together, we had several encounters and I proposed to him something that I really wanted to do. And he said, ‘Yes, I can join you.’ And from then on, we began working together in a very leisurely way.”

Zarate’s initial spark - an adult pursued by a child - so intrigued Moore, that the two of them began evolving it co-operatively through a synergistic meeting of minds into A Small Killing, published by Victor Gollancz in 1991. The story concerns Timothy Hole, an advertising executive who has, as Zarate comments, “…countenanced such a big betrayal, that he loses himself. He goes back to the place he was born looking for something of what he used to be.” Zarate continues, “The narrative timing is mine. I told Alan, ‘[Timothy] has to work back through different means of locomotion: a plane, a train, a car, a bicycle and two legs.’ I was very involved in the fact that each chapter should be presented in this way. From then on, Alan began to do his new things. The structure starts from the fact that the story has to go backwards. But what I care more about are the undertones, the moments. And therefore, that’s why I like the kind of analysis he does. I like it because he understood it, not because he agreed with me. When you say, ‘Ah yes! That’s what I intended all along.’ And suddenly, the identity of the little boy is irrelevant. You read two pages and you know who he is. It’s not important. It’s a tiny detail you just put in there. These are the things one includes to explain what is important to oneself, as much as anything. Besides, Alan is a great listener. With him, you get to a point in which you don’t know where one person’s ideas start and the other’s finish.”

Both Moore and Zarate wanted to treat issues that were happening in England at that time. “We had Thatcher defining a great part of the world. England is not and will never be again what it was. And the world has changed, turning into something a lot more reactionary and cruel. You need a machete to go on with life in these times. …Another concern was a kind of inner voice, a concern that Alan shared. It is about how when you are a kid, you think, ‘When I’m a grownup, I’ll plant twenty trees.’ And when you come to that age, and you are a grownup and look at how many trees you planted, you notice you didn’t plant twenty trees, Maybe you only planted two. Then there comes a moment of crisis in which you ask yourself: ‘What happened? Why didn’t I plant twenty trees?’” As an allegorical, redemptive critique of callous Thatcherite values, A Small Killing stands up as one of Moore’s most singular and significant non-genre graphic novels.

Zarate would conspire with Moore once more on an unofficial coda to From Hell, a short story charting Moore’s state of mind on visiting the Spitalfields pub where Jack the Ripper picked his victims. ‘I Keep Coming Back’ ran in It’s Dark in London in 1997 (above), an ambitious collection of new graphic short stories by acclaimed comics scribes such as Neil Gaiman and writers new to the medium like Iain Sinclair and Stella Duffy. Zarate also edited the anthology for Serpent’s Tail and in 2012 expanded it and drew a new cover for SelfMadeHero’s re-issue. “It was originally a very ambitious project. My idea was to make a graphic encyclopedia of London, like Diderot, looking at this city of ours from unusual angles, like the sounds and smells, the traffic of money, the different social tribes that coexist in London. The first book which came out in this series was It’s Dark in London, graphic short stories about the city after the pubs close. If this book sells well, other titles will follow. I am interested in seeing what happens when writers, film-makers and poets work in a different language - comics. You mix them and you wait for unexpected results. As Iain Sinclair said, ‘To seek out the dissolution of fixed forms, document morphing into fiction, catalogue into poetry, text into performance’.”

By far Zarate’s most productive collaborator is his fellow countryman and a former colleague in advertising, Carlos Sampayo. “Carlos and I met in Buenos Aires in the mid-Sixties, working for the same advertising agency. He was a copywriter, I was an art director and we were very successful as a creative team. We became friends and a year after I left for Europe, he and his family followed. They settled in Spain. We did a few short stories of 8 to 10 pages for Alter Linus, a monthly Italian comic magazine, stories that much later were translated into English and published in the British magazine Crisis.”

This was a boom period in graphic novels in Britain, buoyed by the tremendous success of Spiegelman’s Maus, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen and Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns. At the time, I did A Small Killing with Alan Moore for the book publisher Gollancz, who had no previous experience in comics or graphic novels, but was very excited about them. A revival of comics was predicted, a new boom in graphic novels was looming, so a few graphic novels were commissioned. However, the reality was that artists, writers and publishers were ready to produce straight fiction stories in comic books but the readers were not there. At that time, comic readers were only very faithful to superhero stories, so the balloon burst.”

Zarate turned instead to the vibrant French market for bande dessinée albums. “Carlos Sampayo and myself thought it was time to start working together again. We worked for ten years for French publishers. We did three books together. Trois Artistes à Paris published by Dupuis (above), and Fly Blues and La Faille [ or ‘The Crack’, set in London], published by Futuropolis. The way Carlos and I worked together is quite similar to the way I did with Alan. I presented Carlos with an idea I really wanted to work on and develop. If Carlos says yes, that is when we began working on the idea, slowly building an story around this idea, this sentiment. He was coming to London or I was going to Barcelona, and during the day we did not talk about the book at all, we talked about what was going in his life, what was going in my life, films we saw, books we read, we talked about food, talked, walked, and by the evening we would always have something out all these exchanges that fed the story.That s how we worked, almost without ourselves noticing, so that in a very organic, natural way the story was growing. This is the way I prefer to work if I work with someone else.”

Zarate’s latest graphic novel, The Park, his first as both writer and artist, might have also debuted in France but he was drawn back to Britain by the fresh energy in the burgeoning graphic novel scene. “Back in Britain a younger generation was coming up with wonderful stories, something very interesting was happening here, women were involved this time, which is an incredible thing to break into the boys’ club. Young women bringing their own experiences, their own way of telling stories, their energy is all to the good. It enriches the scope of what can be done in this wonderful language of ours. This time I see a growing readership with a genuine interest for comic books telling straight fiction and I see a new breed of publishers too. So I published The Park in Britain.”

As a way of warming up to crafting his debut full-length graphic novel, for a few years now Zarate has been creating short stories from time to time in Fierro, a monthly comics magazine in Argentina. “The setting of these stories is the neighbourhood where I live when I go to Buenos Aires. The stories are 6 to 8 pages in black and white. They have helped me to flex my muscles and gain confidence when I started thinking about a bigger project. I hadn’t done a solo graphic novel before because I hadn’t had the need. I was happy working, sharing my dreams and nightmares with somebody else, until gradually the need, the certainty, the desire to be the sole author of my work arrived, and that’s the case with The Park. This seems to be the natural evolution of my creativity.”

The Park is set in and around Hampstead Heath, Oscar’s neighbourhood in London. He contrasts its serenity with one incident there which triggers repercussions among two fathers and their offspring. “One of the themes of The Park is that, contrary to what a lot of people are trying to make us believe, the class struggle is still on. It may take a different, more confusing form, but issues of inequality and abuse of power are as bad as they have ever been, if not worse. Something happens in the park, and each of the four characters have a different take on this event. Every human being is in continuous construction, made up of genetic, familial, psychological,cultural and socio-economic factors. Every day this ‘work in progress’ has to deal with whatever life throws at it. These four characters respond to the aggression according to their total makeup, and their social position is a significant factor in all this. Their disagreement, their tension gives the pulse to the story. Everybody talks but nobody is listening.”

One other big influence on the book are the silent movie comedies of Laurel and Hardy. “I love Laurel and Hardy films, they are geniuses, I’m always finding new meanings in their work. When The Park was in its beginning stages, I was thinking about humiliation as one of the themes, people being humiliated on a daily basis. There’s something very profound and disturbing about human relationships in their films, they have many levels of interpretation, about what they do and what we don’t dare to do, about why I can’t live with you and I can’t live without you. They act out on everything they feel, they don’t repress it. They aspire to be accepted by the standards of bourgeois values, they want the house, they want the wife, they want the car, but at the same time they are full of contradictions. What they actually do is to destroy everything they want, they always fail to achieve what they wanted at the beginning of the film, they always fail. What is funny is that in every film, they fail better and better. Laurel and Hardy mirror some aspects of each of the characters in The Park.”

The setting of his story also plays a vital role. “For me Hampstead Heath is a miracle happening every day in North London, a common space, a place of nature, a place of wonder. In the middle of a very urban environment you can get lost in its woods for a few minutes, and if you allow yourself, you can dream about a time before industrial life, about yourself in history and an oak 400 years old is telling you everything is all right.”

Zarate is now entering his Seventies and is clearly in his prime. “I’m working on a book for SelfMadeHero, black-and-white, around 160 pages, about Sigmund Freud’s first case, Hysteria and I’m working again with Richard Appignanesi. Meanwhile, ideas are floating around my head for my next book and I can see a few things are beginning to connect. I’m charged, I can see my work improving, I’m even more in love with comics than before. This is where I love to be now, writing and drawing.” It’s as if Oscar Zarate has truly found that fulfilment which he was promised all those years ago by that correspondence course advertisement.

A version of this Article appeared in Comic Heroes No.22 Jan-Mar 2014.

Photo © & courtesy of Etienne Gilfillan