Moebius & Jean Giraud:

Leading A Double-Life - Part 1

From sci-fi fantasies to gritty westerns, welcome to the incredible double life of Moebius and Jean Giraud, the two sides of one of France’s most brilliant comics geniuses.

Even if you have not yet read a single comic by Moebius, let alone Jean Giraud, you have probably already been dazzled by his visual imagination unleashed in major science fiction movies. He has not only contributed directly through crucial concepts for costumes and creatures, for example in Alien, The Abyss, The Fifth Element and Tron, but his work has also unmistakably influenced many directors including George Lucas on Star Wars and Ridley Scott on Blade Runner. Lucas has said how he has been “...impressed and affected by Moebius’s keen and unusual sense of design and the distinctive way in which he depicts the fantastic.”

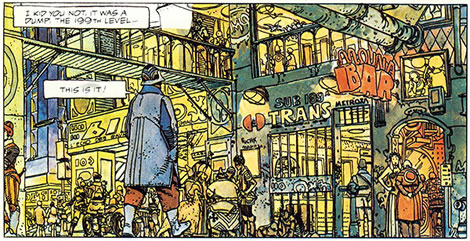

Take one look at Moebius’ short story The Long Tomorrow, published in Métal Hurlant magazine in 1977 and written by the late, great screenwriter, director and Star Wars special effects wizard Dan O’Bannon (1946-2009), and you’ll quickly see how much their soaring vertical cityscapes and gritty urban future inspired Blade Runner five years later. A lot of what we now take for granted as the modern cinematic style of science fiction can be sourced back to the French revolution in comics ignited by Moebius and his fellow innovators in the early Seventies.

Before Moebius and the infinity of outer space, there was Jean Giraud and the wide open spaces of the Wild West. Growing up in the mundane suburbs of Paris, young Jean was already selling his earliest comic strips to magazines by the age of sixteen, inspired by his love of American cowboy movies and his favourite western comics from Belgium, Lucky Luke by Morris and Jerry Spring by Jijé, alias Joseph Gillain. In the summer of 1956, aged 18 and studying textile and wallpaper design at art school (he failed to qualify for the illustration course), Jean used his earnings from his comics to fly to the States and take a Greyhound bus into Mexico City, to join his mother who had moved there and remarried.

On this extended vacation, he was adopted by a group of local artists and radicals who introduced him to philosophy and politics, modern jazz, playing chess, the magic of the desert and the enlightened use of marijuana, not merely for escapism, but to enhance creativity. This different attitude is contrasted in two famous later comics. Whereas in Stoned Again! American undergrounder Robert Crumb would show a dopehead dissolving into gloop as he puffs away, in The Horny Goof Moebius storyboarded 24 frames of a man whose click of a finger sparks a similar bizarre mutation engulfing his whole body, but continues with a second eruption as the egg-like casing releases a tiny man from within. This rebirth sums up Giraud’s Mexican trip, the first of several. “I met Mexico and it completely transformed me.” It marked the start of his personal and artistic transformations, the journey to becoming Moebius.

Returning to France too late to complete his third year at school, Jean pursued comics and became assistant, inker and eventual collaborator on Jerry Spring, acquiring Jijé‘s passion for absolute authenticity. Eager to make a name for himself, Giraud began signing his solo humorous strips for the satirical magazine Hara Kiri under the pseudonym Moebius from 1963. What he began as a playful pun on the German mathematician Möbius, whose ‘strips’, discovered in 1858, were not comics but enigmatic loops of paper twisted in the middle to create one continuous surface, would grow into a perfect symbol of his dual yet singular identity.

Meanwhile, as Giraud, he had met the leading adventure writer Jean-Michel Charlier, who co-founded in 1959 with Asterix co-creator René Goscinny the pioneering French weekly Pilote. At first, Giraud failed to interest Charlier in the western genre, but Charlier’s own visit to the Mojave desert changed his mind. When Jijé turned down the opportunity, Charlier approached Giraud and in 1963 they began the serial Fort Navajo in Pilote. From the opening pages set after the Civil War, US Cavalry Lieutenant Blueberry emerged as the most charismatic character and eventually became the series’ star and title. Excited by French New Wave cinema, Giraud using the pen-name ‘Gir’ drew on the moody actor Jean-Paul Belmondo to initially depict Blueberry. “For me, he was a spokesman, a symbol for an entire generation. I had to capture the Belmondo persona and then work a little alchemy. And ultimately all that remained was the broken nose.” Reflecting this imperfection and the spirit of the early Sixties, Blueberry was far from your typical action hero. He was rebellious, anti-authoritarian, cynical, flawed, often an unwitting pawn in others’ schemes, and later sometimes resembling Keith Richards or Charles Bronson.

Blueberry’s personality and perspective also became increasingly complex and compelling. By the series’ second story arc, despite his promises of fair treatment, Blueberry fails to prevent the Native Americans from being massacred by the US army. Giraud’s return trip to Mexico in 1965 would affect him profoundly, as he experimented further with hallucinogenic mushrooms and solitary meditation. This led to his incorporation in Blueberry of vivid, multi-coloured landscapes and wildernesses, vistas never before seen in Western movies, and a greater involvement in the plots and scripts, for example a fourth cycle in which the Lieutenant sides with the Indians and helps them return to Mexico. Since Charlier’s death in 1989, Giraud has been steering the saga alone. Across some thirty albums between 1963 and 2005, Blueberry stands as one of the world’s greatest Wild West masterpieces, in comics or in any medium.

Change was in the air after the Paris protests of May 1968 but the publishers of French comics were lagging behind the times. Early in 1972, in protest at a ‘Masked Cucumber’ story being rejected by Pilote editor René Goscinny, cartoonist Nikita Mandryka was joined by Claire Brétecher and Marcel Gotlib in a landmark walk-out. By May, the trio had set up their own satirical magazine, L’Echo des Savanes (The Echo of the Savannas) to self-publish whatever they chose. For now, Giraud stayed on at Pilote and in January 1973 Goscinny approved his most unconventional solo comic yet, The Detour. Though still signed ‘Gir’, this surreal, metaphorical road trip featured Giraud himself and his family and marked the birth of the Moebius style of art and story, with its intensive rendering techniques, fantastical transitions and stream-of-consciousness narrative. There was no going back now. Instead of some brief offshoot, this ‘detour’ would usher Giraud into a realm of unprecedented creative freedom.

While concluding another Blueberry album, his last for two years, Giraud revived his Moebius nom-de-plume to cut loose on Le Bandard Fou (The Horny Goof) for his cronies at L’Echo des Savanes to publish as an uncensored underground album. On alternating pages, he interweaves the wordless 24-page metamorphosis described earlier with the zany mating rituals between the hapless Goof and the predatory Lady Kowalski on the pleasure asteroid Flower. Every form and surface vibrates with remarkable three-dimensional modelling and subtle stippling and linework, heightened to the pitch of a feverish dream.

The big breakthrough came on December 14th 1974, when Moebius teamed with fellow Pilote artist Philippe Druillet, writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet and manager Bernard Farkas, all fans of the latest science fiction, to found another independent outfit, Les Humanoïdes Associés, or ‘Associated Humanoids’. In 1975 they launched their progressive flagship anthology Métal Hurlant. Moebius welcomed this as “a new open-minded venue, where a different type of story was being created but also, a novel kind of rapport between reader and creator.” Finally he could liberate his comics from Blueberry‘s choking captions and balloons and develop a fully-painted approach to colouring. The results were five silent, jewel-bright vignettes, charting the exploits of Arzach/Arzak, an uncanny man in a cloak and pointed hat soaring over alien worlds on the back of pterodactyl. After these came Le Garage hermétique (The Airtight Garage), two-, three- or four-page instalments invented from one issue to the next with no script or planning. “This was like a research laboratory open to the public. It went on like that for almost two years. Every month the series would descend into pure improvisation.” Here he revived the wicked queen Malvina on the asteroid Flower and introduced his eccentric David Niven-esque colonial, Major Grubert, traversing planes of reality, escalating into a glorious, non-linear multi-dimensional puzzle.

Around this time in 1975, Moebius first encountered the Chilean-born film director Alejandro Jodorowsky who swiftly recruited him to work on the storyboard, costumes and characters of his next movie, an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel Dune. While this never got made, it brought Moebius, H.R. Giger and Dan O’Bannon together, who went on to collaborate on Ridley Scott’s Alien. Originally a playwright in Mexico and wild showman of the absurd involved with the Parisian Panic Movement, by this time Jodorowsky was looking more within himself and became Moebius’ mentor.

Moebius and Jodorowsky combined their prodigious imaginations on several comics, notably the Incal series of six albums over ten years. 2It has a quality that puts science fiction back to when science fiction was a metaphysical reflection on man, time and space.” Selling more than one million copies in France alone, it is Moebius’ biggest success to date. It also prompted Stan Lee to work with Moebius on a two-part Silver Surfer special, Parable.

Meanwhile, as part of his burgeoning personal mysticism, Moebius branched off in 1984 to devise a fresh series of his own cosmic reflections, The Aedena Cycle. This started as a promotional album, an incentive for Citroën car dealers, but soon expanded into a sensitive eco-fable about two marooned explorers from an artificial world, Stel and Atan, who rediscover nature and their true selves. Most recently, his principal albums have been a six-volume self-published series Inside Moebius. Harking back to his Garage adlibbing, he has created these spontaneously in his sketchbooks, whenever the muse strikes. The mature Moebius delights in toying with his pantheon of creations, thrown together in the baffling Desert B, berating their author and struggling to make sense of their own story or lack of it. Literally looking inside his own head, he can also move into autobiography, colliding multiple versions of himself at different ages, or even bringing on Osama Bin Laden in the first volume. Playing as never before with the conventions and forms of comics, these climax in a delirious explosion of metamorphoses, like the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

This year has also brought the unexpected return of Arzak. As he explains in the new book’s afterword, “This all began with the Japanese, a vague animation project, the sort that is always being born in that purgatory of hoping to adapt a comic to the big or small screen.” Unfilmed, left in a drawer, the script resurfaced and prompted this first part of a trilogy of startling oversized albums. Arzak speaks and we start to learn about his special relationship with his part-living, part-technological pterodactyl and his half-breed background in what comes close to being an allegory for the American West. The deserts of Mexico, of Blueberry, of Inside Moebius, are also the desert of Arzak.

Moebius, and Jean Giraud, may have turned 72, but his artistry and creativity are as dynamic as ever. For proof, his first major retrospective exhibition is filling the Fondation Cartier in Paris until March 13, 2011, he has co-directed a striking 8-minute pilot for a proposed 3D animated movie based on one of his Stel and Atan tales, rumours are rife of another Blueberry and the latest word is that he has been brought back to Hollywood. No doubt many more wonders await us on that infinite horizon.

This article first appeared in Comic Heroes Magazine issue 4, on sale now.