Indian Comics:

A Visual Renaissance

Something extraordinary is happening in 21st-century India. Many geopolitical experts seem convinced that this vast, complex nation is blossoming into one of the economic giants on the global stage, rivaling China. Recently, the eyes of the world, or at least of those interested in sport, have been focussed on the Commonwealth Games in New Delhi and its complications and bad press. Putting these aside, as well as the success and export of Bollywood movies, Indian cuisine, cricket and contemporary art, another field is newly ascendant here, that mix of industry, entertainment and culture that produces comics and graphic novels.

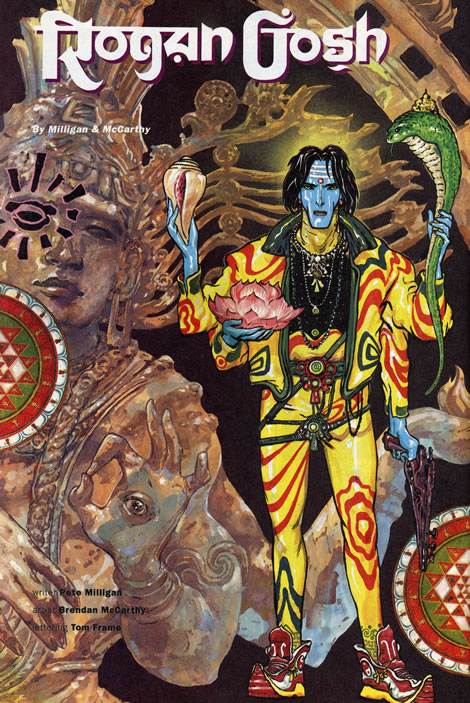

Since 1967, India has had its distinct modern tradition of colour comic books, closely akin in format and style to America’s Classics Illustrated titles, with their fully painted covers and solid, workmanlike interior illustrations, in the form of the famous, phenomenal series Amar Chitra Katha. The name translates as “Immortal Captivating (or Picture) Stories”. Founded by Anant Pai, they are predominantly worthy, educational and aimed at teaching children about their own cultural heritage. Endlessly repackaged and reprinted, these titles are still selling, offering versions of legends, biographies and histories in accessible, acceptable strip form, as well as the monthly 72-page magazine Tinkle. These days the company is diversifying into audiobooks, animated cartoons on Cartoon Network, DVDs, E-comics and more online. After a gap of four years, their latest title about Mother Theresa was released in August 2010 to mark the centenary of her birth. Generations have grown up reading Amar Chitra Katha and not only in India. The comics are exported, for example to the UK, and were a major influence on British artist Brendan McCarthy when he discovered them in the shops of Southall, known as the ‘Little India’ of London. Struck by their heightened, vibrantly coloured front cover artworks, McCarthy developed the look of his Indian-themed psychedelic fantasy Rogan Gosh (a play on the dish rogan josh), which co-created by Peter Milligan for Revolver in 1990.

Rogan Gosh

Several different interesting trends have been emerging in more recent years in Indian comics. First, a more modern-looking mainstream production has developed, heavily inspired by the imported melodramatic, detailed, computer-coloured stylings of superhero and fantasy comics from America. As well as some excitement over a special Indian version of Spider-Man in 2004 from Gotham Entertainment, this sector gained a greater profile in 2006 when Richard Branson of the Virgin Group partnered with filmmaker Shekhar Kapur, renowned author Deepak Chopra, his son Gotham and fellow entrepreneurs Sharad Devarajan and Suresh Seetharaman to found Virgin Comics in New York and Bangalore. From its Indian base, many highly skilled local artists set to work illustrating scripts by others based on big-name concepts, notably from writers like Deepak Chopra, major movie directors like Guy Ritchie and John Woo and celebrities like Eurythmics frontman Dave Stewart. A separate Shakti line (Sanskrit for “power”) set out to reinterpret and often update specifically Indian subjects, such as Devi and The Sadhum while the sixteen issues in Deepak Chopra’s India Authentic series re-presented great legends, essentially a slicker, flashier take on Amar Chitra Katha’s approach.

The Virgin Comics concept may have been to “create content that not only reaches a global audience but also helps start a creative renaissance in India”, but it quickly became clear that much of the line was geared to preparing low-cost market-testing, audience-building and pre-production design and promotion for commercial, generic movie options, which did not fully materialise. There were exceptions and one progressive project was to have been 18 Days, a Grant Morrison-scripted animation project, a science-fantasy spectacular based on the Mahadbharat saga. Morrison’s ambitious vision sadly fell victim to the closure of Virgin Comics and its management buyout by Liquid Comics in 2008. This summer, however, Liquid and Dynamite Entertianment have compiled a hardcover collection of Morrison’s scripts with hyperdecorative illustrations by maximalist artist Mukesh Singh to convey some idea of how eye-popping this might have been, and who knows, might yet come to be, perhaps outdoing Avatar as some HD-3D animated extravaganza.

18 Days

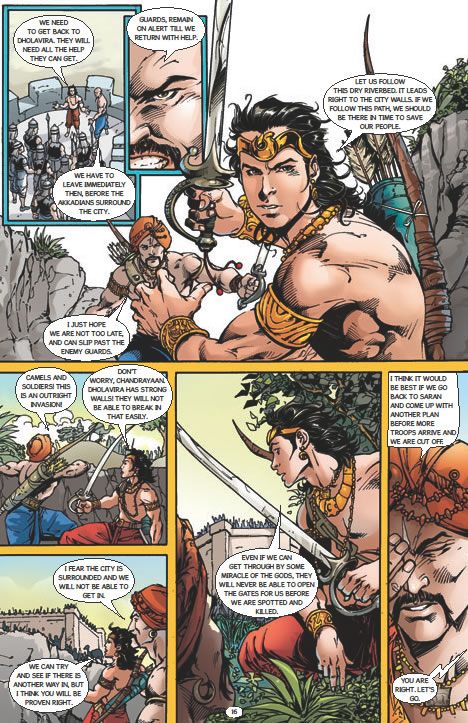

Another recent operation, also combining the traditionalist approach of Amar Chitra Katha with the up-to-date graphics and production of Gotham and Virgin/Liquid, is Campfire. Set up in 2008, they have begun very safely by adapting out-of-copyright and rather overfamiliar classics of Western rather than Indian literature, as well as biographies of inspiring figures, and tales from the Mahabharat and Ramayana and other world mythologies. Throughout, their standard of computer-coloured art is consistent but seldom very distinguishable. More interestingly in terms of content, in 2010 they have started to introduce original stories. These range from slick gritty urban crime fiction in Photobooth written by American author Lewis Helfand and drawn by Sachin Nagar, to a well-researched recreation of the ancient age of the Indus Valley civilisation by archaeologist Sanjay Deshpande, illustrated with bravura by Lalil Kumar Sharma in In Defence of The Realm. It will be in their originated productions that Campfire look set to break new ground and stand out.

In Defence Of The Realm

Moving now to another trend, in the wake of world masterpieces from Maus to Persepolis, the last few years have brought the first flowerings of highly distinctive literary graphic novels in India, notably from major publishers like Penguin and Harper Collins. This evolution first came to light for me when I had the luck to meet the charming, energetic Sarnath Banerjee over a print in a London pub around 2003. I discovered that he was a former Escape reader, now completing his MA in Image and Communication at Goldsmiths. He was full of enthusiasm as he completed The Corridor, a quirky, evocative, unmistakably Indian-rooted portrait of urban alienation and imagination centred around New Delhi’s cluttered downtown shopping district Connaught Place, where one Jehangir Rangoonwalla dispenses wisdom, tea and second-hand books. Published by Penguin India in 2004, it became India’s first true original graphic novel and sold out of its first print run in only one month. Positively reviewed, it seemed to be tapping into a literate audience hungry for a fresh storytelling form. Despite also being a documentary filmmaker, Banerjee told Things Asian in 2004: “In films the quirky ideas always end up in the dustbin. The freedom you get in working on a comic book makes you dizzy, especially if you get a good editor who lets you dance around and do your own stuff.”

The dancing Banerjee came back to London as a guest at the Comica Festival and was an inspiring tutor for the Lingua Comica project with the Asia Europe Foundation in 2007. This coincided with his follow-up graphic novel, again for Penguin India, The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, a delirious 280-page concoction about the eponymous book in which a wandering Sephardic Jewish trader has recorded the scandalous escapades of British officers and the local elite in 18th century Calcutta. Banerjee’s wanderings have continued to take him all over the world and into many related fields, including contemporary art, selling out of his show of comics-inspired art at London’s Frieze artfair in 2009, and documentary reportage in comics form. For free-thinking, humanist website Spiked he produced The Harappa Files about India’s shadowy censors who banned a soft-porn cartoon website about a sexy sister-in-law, and for the latest issue of Naked Punch a report on a detective couple from Sao Paulo.

One of the essential evolutionary elements, in my view, in fulfilling the maturity of any country’s graphic novel culture must be the ever-growing contributions of women artists. Again and again it has been proven that their voices and views are vital for comics to redress the balance from male-dominated tropes and conventions. In India, 2008 brought the publication of Kari, the first major graphic novel by an Indian woman cartoonist, Amruta Patil, whom I profiled and interviewed for Art Review. I found it revealing that Patil does not see herself as a comic artist but as a writer who, for now, chooses to use images along with her words. And her use of words is vibrant and captivating. Not for nothing did Times reviewer and novelist Neel Mukherjee acclaim her writing as “...a thing of radiant beauty: witty, smart and swaggering, brightly knowing without ever falling into archness, illuminated by frequent flashes of poetry.” Patil is part of an undeniable trend, encompassing Posy Simmonds, Marjane Satrapi, Lynda Barry and Alison Bechdel, of women who have been bringing an alertness to phrasing and prose to enhance the texts in their comics. Equally enriching are Patil’s visual sources beyond comics, of which she cites “Indian temple art, Mughal Miniatures ...[and] Mahayana Buddhist imagery.” As we will see below, India’s artistic traditions are also now feeding into other new forms of local comics. What is more, Patil’s current large-scale undertaking Parva sees her working far more visually, in multiple styles and in full colour, as she attempts her personal take on the Mahabharat epic.

Delhi Calm

Harper Collins this year has issued one of the most politically engaged and controversial Indian graphic novels, Delhi Calm, the solo long-form debut by Vishwajyoti Ghosh. Back in 2007, I met Ghosh when he was picked as one of 14 Asian/European young artists to come to the Comica Festival in London for the Lingua Comica cultural exchange programme, the second organised by the Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF). The results of these seven pairs of encounters and collaborations, first via a blog and then in person, were finally published by ASEF last year in a smart 160-page paperback designed by Titus Ackermann, for which I wrote the introduction. Ghosh has written and drawn other short pieces, for example in the Ctrl.Alt.Shift Unmasks Corruption anthology which I helped to co-edit for last year’s Comica.

Delhi Calm is clearly his most sustained, significant opus, a deeply ironic title for a 256-page excoriating excavation of a tumultuous time in Indian history known as The Emergency. For 21 months, from 25 June 1975 to 21 March 1977, on advice from Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (who was no relation to the late Mahatma Gandhi), the then President of India declared a state of emergency, permitting her to rule by decree and suspending elections and civil liberties. Such extreme state measures were somehow worded to confirm still to India’s constitution and were enforced in the name of saving the nation from internal pressures for change. This may all sound hard to believe today. Ghosh was only three at this time and came to realise that many of his peers, and generations of Indians younger than him, had little or no understanding of these dark days and their troubling echoes through to the present day. They certainly won’t going to learn about this through the historical comics of Amar Chitra Katha, whose biographies of post-Independence figures have, perhaps unsurprisingly, not included one on Indira Gandhi so far.

Ghosh humanises this period through the interwoven and interrupted lives of three young idealists, the poet Vibhuti Prasad, the pragmatist Parvez Alam, the ‘master’ Vivek Kumar, all members of the Naya Savera Band, who struggle to inspire ‘total revolution’ among the rural population. They drift apart, eventually reuniting under the Emergency in Delhi, nicknamed ‘Powerpolis’. Ghosh avoids identifying the politicians and leaders and in his title-page author’s note declares, “This is a work of fiction. Self-censored.” This uncensored admission of self-censorhip only serves to highlight what he is hiding and showing. Censorship of the press was of course one the key controls put in place during The Emergency, personified here in the Smiling Saviours, suppressing and punishing any questioning from behind their sinister grinning masks. It is also quickly apparent who the woman leader Mother Moon and her two sons, Pilot and Prince, really are. Ghosh has some cause to be cautious in naming names. In 1984, Indira Gandhi, re-elected as Prime Minister, sued Salman Rushdie for defamation caused by one sentence about her in his 1981 novel Midnight’s Children, also set in and highly critical of The Emergency. To avoid the risky course of a court case, Rushdie’s publishers Jonathan Cape had to give way and delete the offending sentence, despite the fact that its assertion was already printed before and commonly known. When Ghosh’s artwork was exhibited earlier this year, it caused discomfort and debate; the Emergency still haunts 21st century India.

Awash in sepia stains, switching to greys for sections of background material and newspaper propaganda, Ghosh’s tense, angular drawings counterpoint the cheerful official double-speak - ‘Emergency Not A Threat To Democracy But A Measure To Safeguard It!’ - as he shows the syringe and razor-blade of the mass sterilisation programme or the enforced clearances of ‘Socially Undesirables’ from their slum homes. Far from a solely backward-looking, hindsight-informed ‘satire’ of some receding past, Delhi Calm is an impassioned critique, expanding on the political cartoon tradition but harnessing it to powerful and sometimes extended prose passages. Ghosh is not out merely to ridicule or exaggerate, but wants to plunge readers inside the warped psychological state of the nation and make them consider how the echoes of the Emergency, the in-built, endemic corruptions of the system, reverberate still to this day, wherever and whenever patriotic duties deny people their freedoms supposedly ‘in the interests of the state’. The chilling dichotomy of this book is that it is both surreal and all-too-real.

I See The Promised Land

Indian graphic novels are taking other forms as well, introducing to comics, and indeed to the medium of the multiple book itself, the visual and storytelling vocabularies from traditional Indian folk and tribal arts. At the 2005 Falmouth Open Forum on graphic literature I was lucky to meet Gita Woolf, the inspirational woman publisher behind Tara Books in Chennai. She and her team have led the way in this area by inviting brilliant artists and artisans to apply their skills to making stories and making beautiful, hand-crafted yet commercially viable books for a global audience. So far these have been mainly for young readers or ‘all ages’. What excites me most here is how this approach can be used to reconnect the graphic novel to its many amazing antecedent narratives forms from around the world and reconfirms comics as a vast, unending human activity. Tara’s first illustrated book for adults in their ‘Patua Graphics’ collection is I See The Promised Land, a graphic biography of Martin Luther King Jr. written by African-American performance poet Arthur Flowers and illuminated by Manu Chitrakar, a Patua scroll artist from the Bengali village of Naya, who performs stories as he unrolls his painted scrolls, pointing to successive panels as he speaks. London-based Italian designer Guglielmo Rossi has designed the typography and layouts to entwine these verbal and visual registers onto a standard printed page. This three-way combo results in a reading/viewing experience like few others, sometimes purely visual or purely text and type, at other times fusions of the two. Publisher Gita Woolf explained to me: “The idea was also to develop the scroll tradition in new experimental directions, and as a three-cornered dialogue, the project was very challenging. The fallout is interesting, by the way - Manu (the artist) is actually creating a new scroll inspired by the book for Arthur and himself to perform with… and we’ve seen a number of Martin Luther King Jr scrolls by different Patua artists, after the story began to circulate among them! And so the tradition meanders on, in its own convoluted way.” I’m sure I am not the only one who can’t wait to see that live performance of this book. Tara have a second ‘Patua Graphic’ coming up, Sita’s Ramaya, a female retelling of this classic by scroll artist Moyna Chitrakar and young writer Samhita Arni.

Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability

Another Indian style known from the 400 or so Adviasi communities of India has been applied this year by Navayana Publishing in New Delhi, India’s only publishing house to focus on caste from an anti-caste perspective, to illustrate Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability. Joe Sacco has hailed this book: “The artists Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam have dropped most of the West’s and manga’s typical comics conventions and boldly use of their own artistic heritage, the Pardhan-Gond tradition, to craft a distinctive graphic biography of one of India’s bravest and greatest leaders, Bhimrao Ambedkar, an ‘untouchable’ and a fierce critic of Gandhi’s. Heavy in symbolism and motifs, Bhimayana is challenging in all the right ways and still conveys with flair who Ambedkar was and why his revolutionary ideas about the caste system still matter so much to the India of today.” It is also the first graphic book in India to be simultaneously published in five languages. The pages I have seen are wonderful, their figures and clothes drawn in intense patterning, faces mainly in profile with large single eyes, and their pages divided into panels by curving, decorated borders. Accusing, pointing fingers are repeated in one panel. Even the balloons have shapes and tails uniquely their own: bird-like outlines for regular speech; a scorpion’s sting as the tail for venomous dialogue; and a distinctive eye in the thought bubbles to represent the mind’s eye. What better art to retell this tale today?

From the self-publishing scenes, such as Bharath Murthy’s print-on-demand movement ComixIndia, compiling three themed anthologies, to Sharad Sharma’s twenty years of Grassroots Activist programmes through World Comics India teaching villagers how to make and use comics and his DevCom comics anthologies tackling development issues, I am sure that Indian comics will continue to surprise and innovate; there are now plans next year for the first Mumbai Comic Convention.

To find out more, I will be talking in London via the wonders of Skype with Vishwajyoto Ghosh in New Delhi on Saturday 23 October from 7pm, when I host hosting a presentation and panel discussion at the new DSC South Asian Literature Festival in London entitled A Visual Renaissance: The Rise of Graphic Novels in South Asia. Joining me in person will be three Londoners: design prodigy Mustashrik, who dazzlingly adapted Julius Caesar for SelfMadeHero’s Manga Shakespeare line; Kripa Joshi, a former graduate of New York’s School of Visual Arts from Nepal who self-publishes her colourful, witty comics about Miss Moti in a style inspired by Mithila (Madhubani) folk art traditions; and Woodrow Phoenix, author of the remarkable Rumble Strip, who visited India last November through The British Council to explore the current comics scene. Also joining us will be S. Anand, co-writer and editor of Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability. Tickets cost £8 including drinks and can be booked here. This event is being held at Q Forum, 5-8 Lower John Street, London W1F 9AU, a brand-new, central-London cultural venue, near Piccadilly Circus. Come and discover more with me about India’s new 21st century comics cultures.

Posted: October 18, 2010