Hergé & The Clear Line:

Part 1

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE LINE

Even in today’s computer age, the genesis, and the final revelation, of so much comic art remains the line. "It’s only lines on paper, folks!!" as Robert Crumb once put it. Ah, but which lines, how many lines, and what graphic qualities of lines will an artist choose, and why?

By learning from his precursors and his contemporaries in Europe and America, the Belgian creator Hergé, pseudonym of Georges Remi (1907-83), distilled his personal approach to these questions in his masterwork, the twenty-three Adventures of Tintin, begun in January 1929 and published as albums between 1930 and 1976 (he left a twenty-fourth unfinished). Over the years, he came to see that "the biggest difficulty with comics is to show exactly what is necessary and sufficient to understand the story; nothing more, nothing less." To do this, Hergé arrived in successive forms at what later, after all of his Tintin albums had been published, became known as the Clear Line.

This is a clarity of line that defined figures, objects, backgrounds, everything, in the same precise outline, stripped of superfluous rendering or shading, and, equally important, a clarity of readability in his panel-to-panel narrations and stories. A clarity so clear that many a child has followed the story long before they can read the words. Independent Hergé biographer Huib van Opstal wrote: "In the Clear Line label, Hergé saw too much attention for the outside aspect of his work. In strip making, he considered his narrative technique and compositional hierarchy equally important to his style of drawing. ‘It took me twenty years to understand that the story is more important than the art.’"

Hergé evolved his insights gradually in stages, so that there are a number of variants of the Clear Line depending on the period of his work. Taken as a whole, no other aesthetic model has exerted such a significant and ongoing influence on comics, in Europe and beyond, as the Clear Line, especially on Hergé‘s fellow contributors to Tintin weekly in the post-war "Brussels School", and on later generations since the ‘70s of his more or less direct and respectful "heirs". In my present survey I intend to trace another (hopefully) Clear Line, the line that links Hergé back to some of his own influences, runs throughout his oeuvre and those of his peers, before connecting, directly or indirectly, to his modern and postmodern successors.

THE LESSONS OF YOUTH

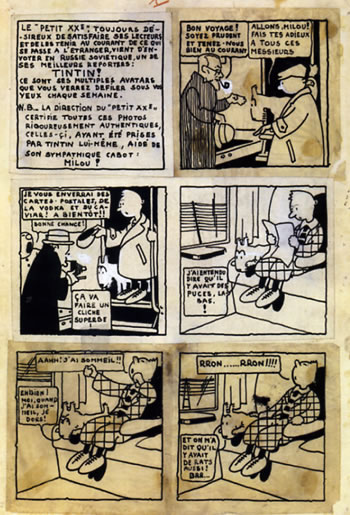

Drawing from a young age, Hergé‘s first teachers were the artists whose works he enjoyed and studied from childhood through to his youthful beginnings as a commercial illustrator and his emergence on the first Tintin stories, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929-30) and Tintin in the Congo (1930-31) in Le Petit Vingtième, the weekly children’s supplement of the Brussels newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century, both titles spelled with "XXe" at first). In the style of the age, the first two decades of the 20th century, many of these artists already demonstrated to him a shift away from overly rendered elaboration and a preference for a refined use of linework, in vogue across the media, eye-catching and communicative, and ideally suited to the rigours of printing. Among the many origins and originators of the Clear Line, never underestimate the practical need to simplify for sharper reproduction, especially on lower quality presses and papers. Fewer lines did not necessarily mean less work for the artist, however. Famously replying to an editor’s complaint that he had not provided enough lines in his drawing for the money, the widely admired British cartoonist Phil May (1864-1903), one grandfather of the Clear Line, once said that he would have charged him more, if he had been able to draw it in fewer lines. An artist after Hergé‘s own heart.

As for specific influences, Hergé had been struck by the animal illustrations of Frenchman Benjamin Rabier (1864-1939) for various journals and books, and especially La Fontaine’s Fables, and later confirmed, "I was astonished by the sureness of line, by the freshness of the flat colours; for a long time, I have considered Rabier as a peak of artistic creation, far above Rubens and Rembrandt." When Hergé picked the first name that came into his head for his new feature, might he have subconsciously recalled reading the exploits of a picture-book boy hero with a blond quiff and knee-length trousers named Tintin-Lutin, who had been created around 1900 by Rabier with Fred Isly? Can the name and visual resemblance by purely coincidental? Tintin’s round face, wide eyes, and tiny nose also closely resembled another French-language children’s favourite from the period, the naive but big-hearted servant girl from Brittany, Bécassine, created for La Semaine de Suzette in 1905 by artist J.P.P. Pinchon (1871-1953) and writer-publisher Caumery (alias of Maurice Languereau, 1867-1941). The beautifully coloured Bécassine stories were compiled into popular hardcover albums beginning in 1913.

In truth, comics were not Hergé‘s first calling. He initially set out on a career as an all-purpose draftsman and graphic designer, and naturally would respond to the latest styles of his day, say as Art Nouveau gave way to Art Deco, and to whatever he encountered in a variety of media from home and abroad. Hergé was obviously aware of the elegant, sinuous fashion drawings of Erté, a memorable nom de plume, also derived from the initials os his real name, but not in revered order: R.T. or Romain de Tirtoff (1892-1990). It may have inspired Georges Remi to reinvent himself as the similar-sounding Hergé, the French pronunciation of R.G., his reversed initials. It couldn’t hurt if his public made the association with fame. This reversed form was also the common form of address in Belgium. He had become used to it from his first day at school, in French as well as in Flemish, the Dutch spoken in the north of Belgium and its bi-lingual capital city Brussels - and his second language.

FROM SILENT FILMS TO TALKING STRIPS

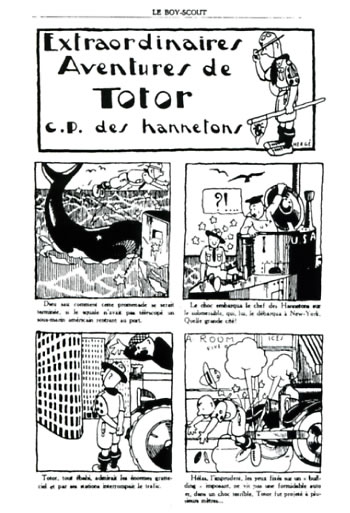

Before Tintin, Totor the Boy Scout was Hergé‘s most concerted attempt at a comic strip character, commissioned from July 1926 by the monthly magazine Le Boy-Scout. It is a modest beginning, noticeably influenced by his frequent visits to silent serials and slapstick comedies in greater Brussels’ many cinemas. Its story of Totor’s trip to America relies on frenetic gags and cliffhangers, mostly made up from month to month, and shrill title credits: "United Rovers presents: an extrasuperfilm" by "Hergé, director". In its format, using the same sized square panels with a mock commentary typeset underneath, Hergé made his own silent film on paper. His Totor strips also resemble the picture stories of French cartoonist Christophe (pen name of Georges Colomb, 1856-1945), published in Le Petit Français Illustré from 1887 to 1904. Christophe’s brittle accuracy, crisp composition, and love of word play unmistakably inspired Hergé, the novice strip artist, who saw his own first strip in print in January 1925, when he was seventeen years young. Totor also hums with what would become another trademark of Hergé: bilingual puns. Being bilingual himself, the son of a French-speaking father and a Flemish-speaking mother, and living in Belgium’s bilingual capital city, Hergé delighted in wordplay with a Flemish slant.

But Hergé was still undecided about what graphic quality of line to use. For twelve years or more he experimented by inking his drawings with a pen, with a brush, or with both, in every technique imaginable. He worked in many styles during the ‘20s and ‘30s, even imitating woodcuts in ink, and was published in many books and magazines, most of it in black and white and some in colour. Huib van Opstal observes:

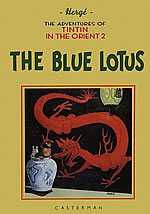

"From his first published drawings in early 1922 in Jamais Assez (Never Enough), the scouting magazine of his college troupe, until the first pages of The Blue Lotus, his quintessential Tintin story first appearing weekly from the summer of 1934 on, he wrestled with his line. In 1928 he inked most of his pre-Tintin strips and illustrations with a brush, using a lot of loosely applied thick and thin variations. His very first letterhead, of 1929, was a little figure riding a big brush! In his very long (139 pages) first Tintin strip of 1929-30, he took great pains to give his inked lines an overall equal thickness, but still inked with a brush. This resulted in often beautiful finished artwork, but was a very unnatural way to use a brush."

Obviously, a lot happened between Totor from 1926 to 1929, and Tintin‘s debut in the first week of 1929. From his first Totor "funny film", Hergé started experimenting with the less familiar language of comics, by slipping into his pictures one minimal balloon, saying "?!..." and two sets of stars for stunned impact, examples of the symbolic lexicon of comics he would use to such effect throughout Tintin. During the last year of Totor, the movies had become the "talkies" as sound caught on. In assorted strips Hergé soon realised how much more effectively dialogue balloons could animate his stories and draw in the reader-viewer.

In 1928, two weeks before Tintin, Hergé published two pages of stunningly American-looking, tabloid-sized comic strips. They were printed side by side on pages 6 and 7 in the December 30, 1928, issue of Le Sifflet (The Catcall), a boorish satirical Brussels weekly, and were the first strips ever to appear in it. One strip, titled Réveillon! (Year’s End Feast!), was set in a busy oyster restaurant where clients were cheated. The other strip, titled Le Noël du petit enfant sage (christmas of the innocent little child), was set in the home of a little Belgian boy with a naughty white fox terrier, clearly prototypes of his future Tintin and Snowy. Both were gag strips buzzing with word balloons and word balloons only. Five more such tabloid strip pages followed in the next half year. Announced with one drawing on January 4 and starting with a double page spread on January 10, 1929, Hergé then launched his Tintin adventures also using this system, insisting on no accompanying redundant commentary beneath the frames, as he had used earlier in Totor and several other strips. Hergé seems to have hidden these seven strip pages from Le Sifflet all his life, probably ashamed of their political incorrectness (notably the outcry over some pivotal doggie poop in the last panel of Enfant Sage). The French Tintinologists missed these strips for well over forty years, until Dutchman Huib van Opstal published the full details about them in his 1994 biography of Hergé.

Hergé had been first introduced to the example of this system through the glories of the American Sunday-page newspaper strips, which he read in French-language weeklies. Through the ‘30s he absorbed ideas from still more differing types of strips as they were translated and when friends brought him the original full-size colour supplements themselves. Among them, he admitted his early admiration for the pin-sharp Art Deco lines, then all the rage in clothes, furnishings, and architecture, the zany humour and wildness of Milt Gross’ Count Screwloose of Tooloose, and the caricatural brio of Bringing Up Father beginning in 1913 by George McManus (1884-1954), in particular his "lovely little round and oval noses which I used, without a scruple!" Might Jiggs and Maggie have been Tintin’s never-seen parents?! Hergé enthused about American strips from the ‘30s as a whole, as well as American cinema, for their "great clarity. The Americans know how to tell a great story."

For Hergé, an equally vital example came from closer to home. He was an avid reader and student of Zig at Puce, the boisterously imaginative French newspaper strip (also in a weekly children’s supplement and complete with balloons), about two plucky kids and their pet penguin Alfred, who embarked on a peripatetic world voyage eventually to New York. Begun in 1925 by Alain Saint-Ogan (1895-1974), his fresh Art Deco drawings and simple, realistic settings, themes and often broad gags are all echoed in the early Tintin. Acknowledging his debt, Hergé visited this older pioneer in Paris in May 1931, when Tintin had only just begun its moderate success in Belgium. "Saint-Ogan had a lot of influence on me, as I admired him, and admire him still: his drawings were clear, precise, ‘readable’; and the story was told in a perfect fashion. It’s in those areas that he influenced me deeply." Saint-Ogan gave Hergé an original page from the strip, whose title prophetically celebrated the "Gloire et Richesse" (Glory and Riches) that Zig and Puce find on their arrival in New York. He dedicated it "To monsieur Hergé, [from] a French colleague, with kindest regards." It has been pinpointed that in his next Tintin album, in which he also sent his character to the New World, Hergé was directly inspired by this very page to create an uncannily similar scene of the boy reporter being overwhelmed by more and more offers of dollars. His debts to Saint-Ogan were considerable. Fame would come.

THE REVELATIONS OF THE BLUE LOTUS

It was on Sunday, May 1, 1934, at 5pm that Tchang Tchong-Jen first rang the doorbell to Hergé‘s apartment. Tchang was twenty-six, one year younger than Hergé, a gifted Chinese student of painting and sculpture in Brussels, and they became instant friends. Tchang’s initial mission was to letter Chinese calligraphy and to give Hergé‘s portrayal of his homeland a Chinese feel, but it blossomed into something deeper. The two of them met on many Sunday afternoons for over a year. China was then being subjected to invasion by the Japanese. After the broad stereotypes, cultural clichés, and largely unpremeditated spontaneity of his first four books, research into other cultures, accuracy and planning began to catch Hergé‘s interest. German and American feature films of the period were making good use of China, and so did Hergé.

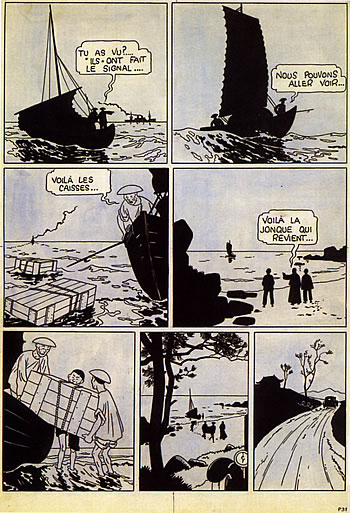

He would always hail Tchang for motivating him to strive for a greater realism and liveliness in his lines. Hergé‘s actual Blue Lotus drawings, however, show virtually no classical Chinese influence, apart from, for example, night scenes featuring silhouettes of boats at sea, or in some rocks and mountain views. In terms of his comics technique, the revelation of The Blue Lotus is the newfound confidence with which Hergé applied the lessons he was learning from the American newspaper strips of the period. He finally resolved the question of "Which Line?" to adopt in the first few installments of The Blue Lotus in the summer of 1934.

THE EFFECTS OF COLOUR

The final ingredient in the crystallisation of Hergé‘s Clear Line was colour. Tintin had always appeared in black and white, first in two-page installments averaging twelve panels in the weekly supplements (occasionally with one or two supporting colours, roughly applied), later in daily newspaper strips consisting of four to eight (!) panels, six days a week. The stories were then compiled into black-and-white hardcovers of some 120 pages, the only colour provided by an additional four to five large, beautiful, and precise plates. The covers of these 1930s albums were adorned with a colour plate too. (An original of the French edition, dating from 1932, was sold at a Paris auction on March 29, 2008, for the stunning price of 764,000 euros.)

The Francophone markets in particular had long been used to full-colour hardcover albums like Bécassine, and to compete with them Hergé‘s publisher Casterman wanted him to change to colour throughout. In Nazi-occupied Belgium, Hergé had already agreed in September 1940 to publish partly redrawn old Tintin stories in the Flemish press, for the daily newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws (The Latest News). Then in October 1940, he agreed to create new Tintin strips for the daily newspaper Le Soir, with apparently few, if any, qualms that it had been stolen from its rightful owners and was being run by collaborators, who filled it with anti-Semitic and pro-Hitler propaganda. Driven by his business sense, if not his politics, Hergé knew that Tintin would help sell the newspaper, and the newspaper would help sell the albums. For all Casterman’s complaints about the paper shortages, the German authorities managed to allocate to them enough paper to print more albums than ever and sales skyrocketed to 324,000 copies between 1940 and 1944. Much of this success was thanks to their new format, as from 1942 Hergé began condensing all the old Tintin albums to around half their previous length, sixty-two pages in total, the size of all future volumes starting with The Shooting Star, and put them completely into colour. It was a sound commercial move: lower paper and print costs meant more profits. It was through this process that Hergé resolved the question "Why?" regarding his line; the much smaller panels we are now accustomed to came into existence because of his economic collaboration during World War II.

Faced with the choices of solids and half-tones, gradations, shading, and other colouring finesses, Hergé would have none of them, and insisted that it was his drawings’ line quality "that formed the true structure of his work." In time an innovative formula was found after Hergé met the former baritone opera singer Edgar P. Jacobs (1904-1987), three years his senior, who had launched himself into comics only in 1942 by concluding a Flash Gordon story by Alex Raymond cut short by anti-American censorship. With Jacobs’ input, Hergé arrived at a system of flat, unvariegated colours, applied within his open, outlined areas, applied onto a second separate board on to which the lines had been printed in non-reproductive blue. Over this, at the printing press, the black linework with the minimum of shadows and spotting of blacks would be printed and preserved in all its clarity. His choice of a light pastel palette was made to help these lines stand out and allow more complex images to be easily read.

Beginning January 1, 1944, Edgar Jacobs was hired by Hergé as his closest collaborator on the revision and colouring of the Tintin albums. Jacobs’ style followed that of his main inspiration, Alex Raymond, from a looser expressiveness to tight academicism. Jacobs instilled in Hergé his obsessive attention to every exacting detail in settings, props, vehicles and costume, making Tintin‘s world more convincing than ever. Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics distinguished the Clear Line for the way it quot;combines very iconic characters with unusually realistic backgrounds. This combination allows the readers to mask themselves in a character and safely enter a sensually stimulating world."

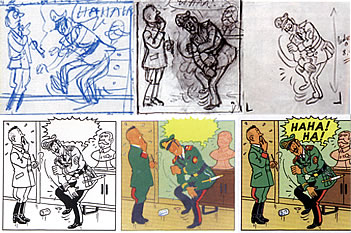

While Jacobs’ accuracy enriched the books, it had never been of such interest to Hergé before. But by the time Jacobs left him in early 1947, Hergé had been "contaminated" by it, to use Benoît Peeters’ word, and it would require the formation of the Hergé Studios and their growing staff of specialists to keep up with his self-imposed demands. Long forgotten were the freedom and freshness of his early comics. The Clear Line became a struggle for Hergé to pin down a character in that one perfect line out of his storm of sketches, which gave him such pleasure that he could push his pencil through the paper. Through the artwork’s subsequent steps, however, he sensed something could be lost, as he reflected in a 1983 interview quoted in Peeters’ 2002 biography:

"When I think I’ve arrived at a good result, with all the spontaneity, all of the lack of thoughtfulness necessary, and all the lack of consciousness possible, then I cool the drawing down via a tracing and I keep the lines that seem to me the best, and which look as if they give the most movement, expressiveness, readability, clarity. Nothing is thought out at the start, but everything goes cool afterwards."

In the process, the Clear Line could sometimes become a "Cool Line". Belgium comics writer and Tintinologist Thierry Smolderen recently told the Comix Scholars email list that the French bande dessinée genius Moebius (b. 1938) often expressed a deep interest in the "suppression of the ego" that Hergé‘s line implied, and the fact that it seemed to eradicate all form of expressionism in a nearly Zen-like manner. In Smolderen’s view, "Moebius wasn’t wrong: actually Hergé‘s taste in ancient and modern art reflected exactly that - he loved Holbein, Ingres, Miró, and as a collector of contemporary art he favoured Lichtenstein, Warhol, Sol LeWitt, Jean-Pierre Raynaud etc. Critic Marshall McLuhan said of comics that it was one of the coolest media. Hergé liked his modern art served real cool too."

Drawing on many, many, influences, Hergé had answered the questions about his line and evolved his personal system of choice to craft his comics. That system would become a discipline for his collaborators in the Studios Hergé and his peers on Tintin Weekly. But as we will see in Part 2, it also led to the revivals in the ‘70s of the Dutch underground and French Ligne Claire, which would spread the Clear Line across Europe and the world.

I am deeply indebted to Charles Dierick, Thierry Groensteen, Bruno Lecigne, Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier, Benoît Peeters, François Rivière, Numa Sadoul, Thierry Smolderen and Pierre Sterckx, the well known Belgian and French Tintinologists, for their researches and insights. A special thank you to Dutch researcher and biographer Huib van Opstal for his wealth of new insights and material.

THE TINTIN LIBRARY:

TINTIN IN THE LAND OF THE SOVIETS (1930)

TITIN IN THE CONGO (1931, redrawn 1946)

TINTIN IN AMERICA (1932, redrawn 1945)

CIGARS OF THE PHARAOH (1934, redrawn 1955)

THE BLUE LOTUS (1936, redrawn 1946)

THE BROKEN EAR (1937, redrawn 1943)

THE BLACK ISLAND (1938, redrawn 1943 and 1966)

KING OTTOKAR’S SCEPTRE (1939, redrawn 1947)

THE CRAB WITH THE GOLDEN CLAWS (1941, redrawn 1947)

THE SHOOTING STAR (1942)

THE SECRET OF THE UNICORN (1943)

RED RACKHAM’S TREASURE (1944)

THE SEVEN CRYSTAL BALLS (1948)

PRISONERS OF THE SUN (1949)

LAND OF BLACK GOLD (1951)

DESTINATION MOON (1953)

EXPLORERS ON THE MOON (1954)

THE CALCULUS AFFAIR (1956)

THE RED SEA SHARKS (1958)

TINTIN IN TIBET (1960)

THE CASTAFIORE EMERALD (1963)

FLIGHT 714 (1968)

TINTIN AND THE PICAROS (1976)

TINTIN AND ALPH-ART (1986, unfinished)

The original (copiously illustrated) version of this article appeared in 2003 in Comic Art Magazine #2, published in the US by Todd Hignite.