Graphic Novels:

The Rise Of The Graphic Novel In Europe

"Where is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?"

For better or worse, so much can hinge on what names and associations stick to a new medium as it emerges, on how people literally come to ‘terms’ with it. In many countries throughout Europe, whenever printed, mass-produced comics began to flourish, the terms for them - often diminutive nicknames, misnomers and insults - have reflected local attitudes and prejudices towards this popular and populist medium.

The same is true of the English term ‘graphic novel’, essentially a substantial, usually complete comic strip narrative in book form traditionally for older readers, which was coined only in November 1964 in the second issue of CAPA-ALPHA, the internal newsletter of the Comic Amateur Press Alliance by the American critic Richard Kyle. Inspired partly by hardback bande dessinée albums from France and Belgium, Kyle proposed a content-neutral but aspirational, to some pretentious, name that could shake off the childish and humorous trappings associated with the word comics and motivate creators and readers to aspire to something more artistic, literary and long-lasting than ephemeral daily newspaper strips or cheap juvenile magazines. The term may have been new in 1964, but the concept was not. In Europe graphic novels in all but name had already existed since the early 19th century and yet their development would be cautious, sporadic and often frustrated from country to country. It would take until the 1960s for the medium truly to start undergoing exceptional re-inventions in format, style and above all content.

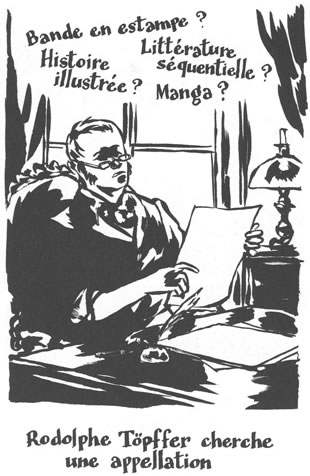

Töpffer by Ayroles

It is telling that for the very first of his 28 Moments Clés de la Bande Dessinée (28 Key Moments From The History Of Comics, Le 9eme Monde, 2004), French cartoonist François Ayroles goes back to that pivotal point in the early 1830s when a Geneva-based schoolmaster Rodolphe Töpffer (1799-1846) was mulling over how best to brand his quirky cartooned storybooks for wider consumption. (1) Floating like thoughts above Töpffer’s head Ayroles puts such concocted combinations as ‘engraved strip’, ‘illustrated story’, ‘sequential literature’. In jest, Ayroles also throws in ‘manga’, another two-part term for comics in Japan. While this modern meaning has only recently become more familiar in the West, in fact the word already existed in that period, having been popularised in 1814 by Katsushika Hokusai to describe his 15 volume collection of sketches or ‘playful’ or ‘irresponsible’ (man) drawings (ga). In contrast, none of these neologisms would suit Töpffer. He was struggling to find a name because none really existed then in French to describe his humorous albums, unfolding their tale over many pages of multiple pictures and captions - in other words, graphic novels.

The Swiss tutor had taken to sketching and hand-writing his loose, lively picture stories purely as a hobby to amuse his students and largely because his short-sightedness stopped him for following in his father’s loftier footsteps as a painter. Nevertheless, what Töpffer self-deprecatingly disparaged as merely his ‘little follies’ or ‘scribblings’ were recognised even before their publication as innovative and full of promise by, of all people, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Despite the elderly conservative German’s loathing for the subversive vogue for satirical caricatures, when he was presented on December 27, 1831 with the draft of Töpffer’s Adventures Of Doctor Festus, he was quick to praise this strange hybridised form:

"[Töpffer] really sparkles with talent and wit; much of it is quite perfect; it shows just how much the artist could yet achieve, if he dealt with modern [or less frivolous] material and went to work with less haste, and more reflection. If Töpffer did not have such an insignificant text [i.e. storyline] before him, he would invent things which could surpass all our expectations." [2]

Who would have thought that Goethe was perhaps the first comics ‘fan’? And their first theoretician and champion was Töpffer himself, who by 1845, the year before his death, felt confident enough about the significance of his work to write the first essay explaining and defending comics. For a variety of reasons, however, the medium would take some time to live up to those great expectations, let alone surpass them.

Despite Goethe’s encouragement, Töpffer held back from putting his books out on the market in 1832, because he was worried that they would tarnish his standing as a newly appointed professor at Geneva’s Académie. Comics have never been an exactly respectable profession. Eventually, he made the first of his landscape-format comical albums available, publishing them himself only for friends in 1833, finally distributing them to bookshops in 1835. To bolster their marketability, he invoked the reputation from a century before of William Hogarth (1697-1764) who like him had self-published his morally instructional Progresses, lionising the Englishman as "an admirable, profound, practical and popular moraliser", and his principal precursor and "master of the genre". (3) In fact, James Gillray in John Bull’s Progress (1793) and other successors of Hogarth adopted Progress to denote some of their multi-panelled single prints satirising an individual’s rise and fall, the term harking back to John Bunyan‘s 1678 allegorical novel Pilgrim’s Progress. Töpffer did not choose to revive the Progress nor allude to the novel, graphic or otherwise. He plumped instead for ‘histoires en estampes’ or stories in prints or engravings, a consciously unassuming descriptive term.

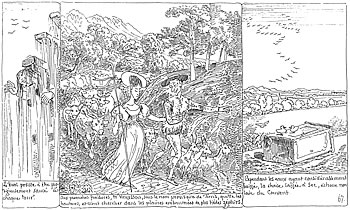

M. Vieux Bois by Töpffer

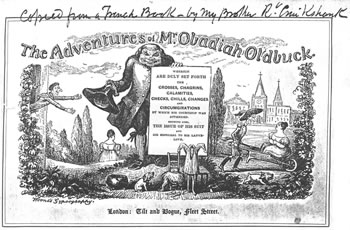

From their modest naming and origins, Töpffer’s albums soon spread around Europe and beyond through translations and copies, authorised and pirated, and inspired several followers. The English cartoonist George Cruikshank, for example, co-financed the English version of Les Amours de M. Vieux Bois, a farce about a hapless, hopeless romantic hero’s pursuit of his ‘Ladye-Love’. It was published in 1841 as The Adventures Of Obadiah Oldbuck.

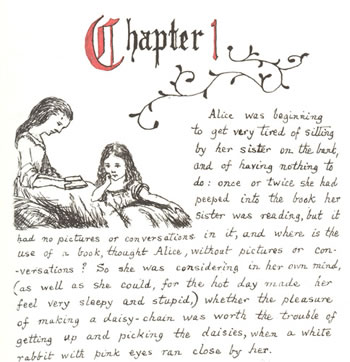

In his personal copy, he wrote on the newly illustrated title page that this was ‘Copied from a French [sic] Book by My Brother R.t [Robert] Cruikshank’. Intrigued, George tried his hand at a Töpfferian comic album himself but when his rather flat Mr Lambkin in 1844 failed to engage the public, he abandoned his ideas for a sequel. A copy of Oldbuck also turned up among the books of Lewis Carroll (1832-98) auctioned after his death. It is tempting to speculate how much this might have inspired Carroll to illustrate his first version of Alice In Wonderland himself as a Christmas gift in 1864 for Alice Liddell, interweaving 37 of his drawings among the 90 hand-lettered pages. In the opening paragraph a listless Alice famously grumbled, "...where is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?" She would probably have loved reading comics, curiosities filled with imagery and often abuzz with noisy speech balloons.

"Where is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?"

Alice from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

From the first version of Alice In Wonderland, written and drawn by Lewis Carroll, and entitled Alice’s Adventures Under Ground.

Another British writer surely aware of Töpffer was William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-63) who took lessons from Cruikshank and illustrated four of his own novels to great success and several picture stories, many printed only posthumously. Finding success as a novelist, Thackeray claimed to craft his comics solely for his amusement, yet to the end he never stopped exploring the form further, making thirteen drawings for a prologue to an ambitious ‘new novel’, left unfinished. (4) Greater rewards and respect from alternative endeavours sidetracked other early practitioners. The young Gustav Doré (1832-83) produced over 500 drawings in 1854 to relate his propagandist Histoire pittoresque, dramatique et caricaturale de la Sainte Russie. Possibly this graphic novel’s extraordinary innovations and variety of styles were too ahead of their times. When in the same year critics and public lapped up his more readily impressive illustrations of the works of Rabelais, Doré chose literary interpretations as his career path.

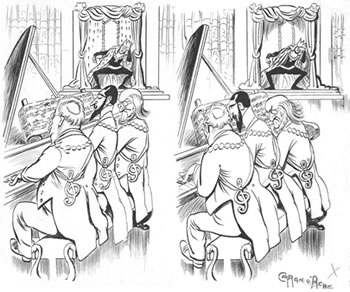

Caran d’Ache

Another loss to graphic novels was Caran d’Ache, pen-name of Emmanuel Poiré (1858-1909), when his enthusiastic proposal in 1894 for a 360-page wordless ‘roman dessinée’ was not accepted by Le Figaro newspaper and he stuck to his short silent vignettes. His thwarted ambition only came to light a century later on the discovery of his proposal and one third of the project completed before his death. (5) Two touching, tantalising memoirs, of his childhood in 1934 and of his early years in Munich as a cartoonist of Simplicissimus in 1954, are the only extended graphic novel-like autobiographies created by the Norwegian artist Olaf Gulbransson (1873-1958).

How different, and how much swifter, the development of adult graphic novels in fin de siècle Europe might have been if there had been a supportive market, and perhaps more acclaim and prestige, to encourage more such writers-who-draw or artists-who-write to pursue long, profusely illustrated fictions. There were occasional flurries such as the stark, politicised woodcut ‘novels-without-words’ sparked in the 1920s by the Flemish artist Frans Masereel (1889-1972). But by and large, comics came to flourish predominantly in early 20th century Europe in the press, in newspaper strips aimed at a young or family readership and in low-priced children’s periodicals. Their minor and mostly juvenile status was echoed in some of the early nicknames comics were given. In Spain, for example, a comic was an historieta or ‘little story’, or tebeo, from the kids’ magazine launched in 1917 TBO (a word play on the phrase te veo or ‘I see you’). Italians still call them fumetti or ‘little smokes’ after the speech balloons puffing aloft out of speakers’ mouths. For years in France, they were known simply as illustrés, short for illustrated stories, or petits mickey - ‘little mickeys’ - after the Journal de Mickey, home to Disney’s mouse.

Compiling reprints of these serials into books, such as Alain Saint-Ogan’s Zig et Puce in France, Hergé‘s Tintin in Belgium or Mary Bestall’s Rupert in Britain, gave rise to the hardback gift album associated with children’s picture books. When paper shortages and more affordable colour printing led to Hergé condensing his first free-flowing versions of the Tintin adventures from over 100 black-and-white pages to fit within 64 pages in colour, or from later models such as Asterix within only 48 pages, this standardised the Franco-Belgian format for years. Imagine novelists being confined to writing say precisely 150 pages and not one word more. Hergé and a few others dared to let occasional tales expand to two books, but most had to accept being straitjacketed by this immutable page count, even if it required excising several pages they had created for the magazine serials.

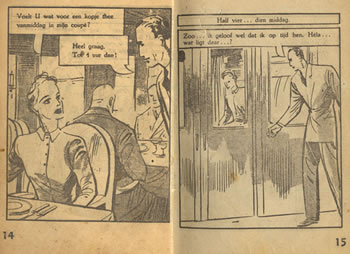

Dick Bos

There were some alternatives, other squarebound, book-like comics, which offered longer, slightly more adult stories, sometimes stirring up complaints and censorship, such as the short-lived Dutch miniature beeldromans or ‘picture novels’ started by Alfred Mazure with the detective Dick Bos in 1941, and the plethora of ‘picture libraries’, a pocket-sized package first conceived in Britain, which evolved into Italy’s increasingly explicit fumetti neri or black comics led in 1962 by master thief Diabolik fantasised by sisters Angela and Luciana Giussani. Also during this period, comics returned to the longer, hardbound quality book as erotica, or classier, pricier pornography, in the shapely forms of Guido Crepax’s Valentina in Italy and Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella in France.

According to French historian Jean-Claude Glasser, the term bande dessinée was first invoked in the early 1940s to refer only to ‘drawn strips’ like those in newspapers, but this would become the widely used term for all comics, especially after the seismic cultural quake in France of May 1968. (6) Championed by intellectuals like Alain Resnais and Umberto Eco, exhibited in the Louvre, elevated as the ‘Ninth Art’, bande dessinée bloomed. Fired up by the taboo-breaking freedoms in imported American underground comics, a rebellious generation of Parisian creators and publishers rejected the timid conventional companies to found their own magazines like L’Echo des Savanes and Métal Hurlant and publishing houses like Futuropolis in the early 1970s and explore more daring themes that spoke to their own age group. Successive individuals and groups have done much the same ever since all across Europe, forcing change and experimentation, often during periods of creative stagnation and social or political upheaval, as with the post-Franco explosion of the El Vibora artists in Spain, or Italy’s contrasting Frigidaire and Valvoline movements born out of the vacuum after the defeated 1977 student occupation of Bologna University. Liberated from the restrictions of simple coloured line art, genre formulas and the standard 48-page container, extraordinary illustrative styles, including fully painted pages, and expansive stories of uninhibited imagination, comedy and fiercely engaged socio-realism enabled the European graphic novel to develop and diverge rapidly. Almost inevitably, once tastes adjusted, certain avant-garde advances introduced by these means could end up being appropriated into the mass-market’s strategies, as former mavericks were able to cross over to become best-sellers, but then the cycle of fresh voices and challenges could commence again. In turn, the medium was buoyed up to varying degrees in many countries by major new public festivals, media and cultural acclaim and governmental support for authors, publishers and the establishment of dedicated schools, centres and museums.

Among the important recent shifts in the contemporary literary graphic novel in Europe has been the move away from genre and heroics towards stories dealing with real life, whether the autobiographical diary and confessional or the reportage, docudrama or fiction based on everyday topics and politics. (7) Suddenly, the richness of the whole of life, the tiniest details and the biggest issues, can be addressed in comics. A pioneer of the autobiographical genre, Olaf Gulbransson would perhaps have been amazed to see imprints, collections, indeed entire publishers such as Ego comme X and Ça et La in France, are now devoted to what in his time was an oddity. One key inspiration for this was the success in many translations of Maus, the American Art Spiegelman‘s account of his father’s recollections of surviving Auschwitz. Its look and format, drawn in urgent, direct black linework in a compact paperback size of nearly 300 pages, set a new benchmark for a plethora of first-person memoirs to aspire to, most notably Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, born in Iran and now a French citizen. It could probably only have been published by the pivotal creator collective L’Association, whose aesthetic approach towards intelligent, uncompromising comic publishing and graphic short story anthology Lapin became models for other European groups like the Slovenian Stripburger, the Finnish Glömp, the Swedish C’est Bon, the Swiss Bile Noire, the Spanish Nosotros Somos los Muertos, the Italian Canicola, and more.

Persepolis

Probably Caran d’Ache would be reeling as well, seeing the current wealth of silent comics unlocking the potential for telling stories purely through visuals, perhaps the most remarkable being Comix 2000, L’Association’s 2,000-page hardback of wordless strips from all over the world. Doré too would perhaps be struck by the impact some political graphic novels can now have, such as Persepolis, being taught to American soldiers in West Point, or Raymond Briggs’ When The Wind Blows which expressed his fury about the British government’s ineffectual public guidelines in the event of a nuclear attack and prompted debate in the House of Commons. Thackeray might recognise his acute social satire in Posy Simmonds’ deftly observed Tamara Drewe.

As for Töpffer, he might well view the diverse landscape of today’s European graphic novel, winning literary awards and adorning museum walls, now absorbing the lessons of manga from Japan and adapting to the different channels to readers offered by the internet and mobile phones, as vindication of his prophetic essay of 1845. He wrote:

"With the dual advantage of greater conciseness and greater relative clarity, the picture story, all things being equal, should squeeze out the other [ie literature] because it would address itself with greater liveliness to a greater number of minds, and also because in any contest he who uses such a direct method will have the advantage over those who talk in chapters." (8)

Töpffer’s name lives on, for example through the annual Prix Töpffer awarded by the city of Geneva since 1997 to upcoming Swiss creators; in fact, sixteen of them in 1998 issued a little box of experimental mini-comics under the delightful title Töpfferware. Maybe the far-sighted Töpffer would also think back to Goethe’s words and wonder at what comics in 21st century Europe have become and are still to become, as graphic novelists continue to "invent things which could surpass all our expectations."

Footnotes:

1. François Ayroles, 28 Key Moments from the History of Comics, Le 9ème Monde, Paris, 2004

2. H.H. Houben, ed. Frédéric Soret, Zehn Jahre bei Goethe, Erinnerungen aus Weimars Klassische Zeit, 1822-32, F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig, 1929, p. 489

3. Thierry Groensteen and Benoît Peeters, Töpffer: L’invention de la bande dessinée, Hermann, Paris, 1994, p. 72 & 187

4. David Kunzle, Father of the comic strip: Rodolphe Töpffer, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Mississippi, 2007, p.171

5. Thierry Groensteen, Neuvième Art No. 4, Centre National de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image, Angoulême, France, January 1999, p.58 & 59

6. Jean-Claude Glasser, Les Cahiers de la bande dessinée No. 80, Editions Glénat, Grenoble, March 1988, p.8

7. This transition is analysed by Bart Beatty in Unpopular Culture: Transforming the European Comic Book in the 1990s, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2007

8. Ellen Wiese, trans. and ed., Enter: The Comics: Rodolphe Töpffer’s Essay on Physiognomy and the True Story of Monsieur Crépin, 1845, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1965

Posted: May 13, 2009This article originally appeared in Third Text, the international scholarly journal dedicated to providing critical perspectives on art and visual culture.