Andrzej Klimowski:

Unlocking The Secret

Thick clouds of cigar smoke and after-dinner chatter billow around the living room in a sprawling communal home out in Ealing, west London, in the early Fifties. While the assorted grown ups, mostly Poles in exile, talk into the night about their hopes for their homeland after Communism, a little boy is left to wander off alone down the long, low-lit corridors. Night after night, he explores, feasting his young eyes through the half-light on the military maps, portraits and engravings which line every wall, losing himself and dreaming in their strange world, until one of his parents finds him and whisks him off to sleep and to dream some more.

It was only later that Andrzej Klimowski, born in London in 1949, learnt that his father had fought during World War 2 for the Polish Resistance, and that it was the movement’s wartime archive that had joined them in his family’s large shared home and in his boyhood fantasy life. Those formative memories lurk throughout the graphic works in Britain and Poland which made his reputation, his distinctive illustration and design on posters for films and plays, as well as on book covers, notably for British theatrical publishers Faber & Faber. One of the playwrights on their list, Harold Pinter, is unreserved in his admiration for Klimowski: "He looks at things head-on but at the same time inside out and upside down, round the corner and through the shattered keyhole. His eye is a microscope, a magnifying glass, a two-way mirror and a crystal ball."

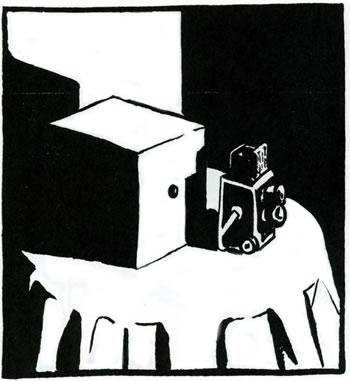

In The Secret (ISBN 0-571-20688-3, Faber & Faber), Klimowski’s new novel-without-words, his sequence of 300 charged brush and ink drawings questions the act of looking and being looked at, the perception and gaze of characters, narrator, author and reader and the tricks the eye can play on us all. Tellingly, he opens and closes with a single eyeball peering through a peephole or shutter. This image instantly reminded me of Roy Lichtenstein’s 1961 pop art painting, based in turn on a Steve Roper comic strip panel (8/6/61) written by Allen Saunders and drawn by William Overgard. Lichtenstein "appropriates" Saunders’ speech balloon, which says "I Can See The Whole Room!... And There’s Nobody In It!" Klimowski, unconsciously it seems, reappropriates the image back into his comic, while that loaded phrase could almost describe the atmosphere of his silent fable.

The story’s key image and preoccupation is the camera and particularly the camera obscura, Latin for ‘a darkened chamber’ with an aperture, through which images of objects or persons outside can be projected, upside down, onto the opposite wall. "The camera was the image I started with. What I like is that it is such a simple object and yet it can capture a whole world inside it. From there I just let the images flow. Drawing is like falling in love. You just go ahead without knowing what’s going to happen to you."

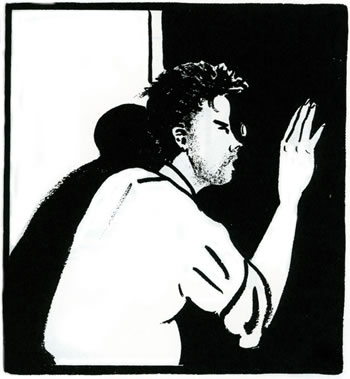

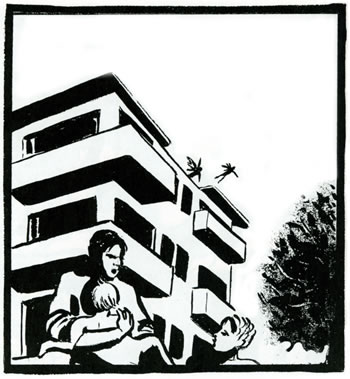

That uncertainty, that not knowing what happens next, describes the giddy feelings of both Klimowski’s leading man, a husband and father of two, desperate to find his wife and children who have inexplicably vanished from their city apartment, and the reader, drawn in as the story unfolds in eerie soundlessness. There is a secret to The Secret but it may not be totally explained. Significant clues emerge in a slide lecture which first presents on a chalk blackboard the basic theory that a camera obscura can somehow capture and combine different elements into new creatures. It then shows unsettling images of the angel or demoness that results from an experiment with a woman (the missing wife?) and a pair of batwings. What is less clear is whether these are merely photographic tricks or are they real living things? In the past, some people believed that a camera could steal your soul; what if a camera obscura could physically steal you or your loved ones away entirely and trap you and transform you inside its interior world? Such tales of unsolved disappearances evoke a Kafkaesque mood of distrust, powerlessness and constant surveillance, a reference too perhaps to the sort of state controls of the Communist system.

As you read on, the lone man’s health and perhaps his sanity decline, but piece by piece, he tries like us to fit the puzzle together. He spies on his two suspicious neighbours projecting a sort of batsignal onto the full moon. Months later, when the rent runs out, his room is cleared by more officials in white coats, leaving the exposed plate from his son’s camera obscura, his last Christmas gift. Developing the last photo taken of his wife and daughter, he makes out reflected in the mirror behind them the silhouettes of the same two neighbours with their own camera obscura trained on them. He investigates, entering a vast camera obscura the size of a building. He eventually discovers a menagerie of freakish creatures, part animal, part human. He frees the winged beings and rescues his children, who emerge naked when he accidentally breaks a giant egg. As for his wife, though, this is left unexplained. "The story is inconclusive because that’s how the world is. Its meanings are impossible ever to pin down." The ending seems to lead you back full circle to an introductory scene of the dishevelled man despairing within a camera obscura, watching as a winged woman projected on the wall behind him suddenly opens her eyes.

These words do scant justice to the provocative, mesmerizing spell cast by the pictures. Every element is carefully considered and rewards close attention, re-reading and referring back, hinting at hidden metaphors and meanings. Klimowski makes pointed variations in his square wordless illustrations. While most tick by one per page floating on white paper, at certain points he may enlarge an image to bleed off a double-page spread, or on two occasions cluster several images together. He may choose to replace his bold brushwork with an architectural cutaway, a Chris Ware-like diagram, or photographic collages. There’s a pared down simplicity to Klimowski’s artwork, strongly inspired by his design studies under Professor Henryk Tomaszewski at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, where the lack of sophisticated technology was compensated by an emphasis on working as directly as possible with basic media and symbols. "I don’t like Surrealism straight, because if everything is strange, then nothing is. But if an image is rooted in the everyday, then strange things can shock."

The event where I first met Klimowski was rather surreal in itself. He appeared at a launch at The Polish Institute, where he projected slides of his book, including slides of the slide lecture in the book, and spoke a running commentary of his story without words. He is a thoughtful, engaging man in his early Fifties, now a teacher himself in illustration at London’s Royal College of Art, when he is not busy with his own exhibitions, commissions and animation projects. The Secret is his second visual novel; his first, The Depository, was put out in 1994 also by Faber, was recently reissued in hardcover in Poland, and an American edition is in discussion.

When I read his stories, I feel as if I am being led by a wide-eyed boy on his night-time wanderings through those shadowy childhood corridors. Neither of us sure of what will be around the next corner.

The original version of this article appeared in 2003 in the pages of The Comics Journal, the essential magazine of comics news, reviews and criticism.