Yves Chaland:

Dreams of Spirou

The Beano, the longest-still-running kids weekly comic in Britain, isn’t the only one with an anniversary in 2013. Also debuting in 1938, Spirou, both the Belgian weekly and the titular hero in his red hotel groom outfit, celebrate 75 years this year. In the land of bande dessinée, Belgium really knows how to put on a birthday party and among the numerous exhibitions and publications (and plans for a theme park), one of the most intriguing items is Spirou by Y. Chaland. This affectionate and revealing investigation charts the deep passion of Frenchman Yves Chaland (1957-90) for Spirou and his long-held dream, ultimately only partially realised, of following in the footsteps of originator of the character, Rob-Vel (alias Robert Velter), and time-travelling back to become another of Rob-Vel’s early successors on the series, following in the footsteps of Jijé (the Hergé-like pen-name of Joseph Gillain) and André Franquin.

Cinebook have started publishing Franquin’s classic post-war version in the UK, beginning with The Marsupilami Thieves. Prior to this, the only source of these albums in English were the single volume of Z for Zorglub from Fantasy Flight Publishing in the USA in 1995, and then about a dozen slightly quirky translations released in 2007 in India by Euro Books. They are still available and I have bought all of them as a very affordable way to get these Franco-Belgian gems in English.

For Spirou and Chaland fans, there are some real treats in this new 112-page, cloth-spined landscape hardback. For example, shown here are five of Chaland’s ‘fake’ alternative covers of the hardbound Albums compiling Spirou weekly magazines. In the early 1980s he drew these front images in the style of Franquin, making the backs patterned to match the originals, which he then rebound himself by hand with a cloth spine and had dried specially at a book binders. His version of the 45th Album (below), in a very Franquin style, shows Spirou as a prisoner being marched off by an African native. Franquin’s own original cover for this 45th Album also portrays this African adventure.

Chaland’s friend José-Louis Bocquet, author of Kiki de Montparnasse, rigorously researches the tangled path of Coeurs d’acier (‘Hearts of Steel’) through both Chaland’s life and burgeoning career and the shifting editors, mercurial decisions and internal politics at publishers and copyright-holders Editions Dupuis, changing from family enterprise to investors’ enterprise (publishers of this very book). Part of the problem was the search for the right successor or successors to continue the plucky groom’s escapades. Bocquet explains: “Since 1979 and the eviction of the Breton Jean-Claude Fournier, whose Spirou was judged ‘too folkloric’ by an eminent member of the [Dupuis] family, Editions Dupuis were looking for a solution to the Spirou problem.”

A recurrent concern was that the character was simply not present enough in the magazine at the time and so there were fewer albums for Dupuis to make money from. The family business quickly came up with the idea of “having the character drawn by several artists in an Italian-style studio”. Different editors pushed different Belgian favourites. After a short attempt by animator Nic Broca, two almost-unknowns, Tome and Janry, arrived in June 1981 and were hailed by Franquin himself. But the Spirou problem remained sensitive and unresolved.

It was in November 1981 that Alain De Kuyssche first proposed to Chaland to take on Spirou, though they had met earlier in July, when Chaland was invited to contribute to a supplement on the theme of pirates and published his first page in Spirou, ‘Jack le Sanguinaire’. This is reprinted here alongside two wacky satirical information strips, ‘Fiches Spirou’, or Spirou Files. De Kuyssche came up with a special format for Chaland’s serial, two single strips per week in black and white with flat grey tones. It’s revealed here that Chaland was paid twice the regular page rate for these episodes. Chaland drew his first and only front cover of Spirou weekly No. 2298, dated April 29th 1982, with Spirou announcing “Chic! Des aventures de moi. Dessinées par Chaland!”, his new adventure about mad menacing robots. The new book reprints all 46 strips for the first time as they originally appeared in monochrome across two editorial pages.

There had been an illegal pirated edition of 1,000 copies in 1984 called À la recherche de Bocongo (below). In 1986 in Métal Hurlant magazine, Chaland drew a self-portrait, shown in this book. He is facing away from us, his expression unseen, holding that pirated edition behind his back and staring at a copy among a dealer’s wall of collectors items for sale at the Paris BD Convention. This was one of the occasions where I met Chaland and where he signed my copy of Jeune Albert, drawing and signing as if it was scrawled by Albert himself!

What is lacking in this re-editon is much of a commentary and consideration about the main attraction, the Coeurs d’acier story itself. Determinedly retro and non-contemporary, its schizophrenic storyline veers between sci-fi robotics and jungle adventures. It all opens in an old-style Brussels with the mysterious (mis)delivery of a robot which proceeds to run amok. In the 6th strip, Chaland drops in a footnote, when Fantasio mentions Professor Samovar, inventor of Radar the Robot in a 1947 story. Chaland’s robot design clearly harks back to Jijé and Franquin’s original and this positions Coeurs d’acier as a deliberate retcon insertion into the early post-war version and as a companion or sequel set in those times.

Chaland connects our duo with the correct customer who ordered the robot, another tenant in their apartment building, one Georges Léopold. This blustering, monocled big-game hunter reveals that after thirty years in the colonies, he recently returned, bringing his faithful servant Bocongo with him, presumably illegally, by packing him inside his baggage. But now, this “poor naïf’, about whom Leopold “almost never” had cause to complain, has mysteriously disappeared. Our heroes are hired to go to Africa and bring him back to his master. Chaland uses some pretty broad signals here - the name Léopold is a clear reference to Belgium’s monarch King Léopold whose regime is notorious for the ruthless exploitation of the ‘Congo Free State’ for its ivory and rubber and the deaths of 2 to 15 million Congolese. The servant’s name Bocongo is another obvious nod to this.

This makes Chaland’s Spirou a puzzle, a deliberate but perhaps problematic attempt to go back in time, style and values, including European attitudes about Africa and Africans, while getting in some deconstruction and digs at colonialist nostalgia and racist caricatures of the period. But the question of how these portrayals would have been interpreted by Spirou‘s predominantly young readers in 1982 is left unaddressed. As is the question of how they are to be received today in this new book, aimed and priced at the mature collectors’ market and not budget supermarket bookshelves.

Spirou and Fantasio attempt to travel to Bocongo’s homeland of Urugondolo but the country is sealed off to the outside world and not welcoming to tourists. In the second row of the fifteenth strip, Fantasio represents a prejudiced idea of an African state - “I can already imagine those backward tribes… The virgin forests, the tom-toms, the ignorant savages… all mod cons!” Reading a guide book, Spirou goes on to correct all of Fantasio’s ignorant assumptions about their destination. The scene echoes Hergé‘s famous page in The Blue Lotus where Tchang corrects the common misperceptions of the Chinese. But Chaland adds a puzzling extra narrative, entirely in pictures in the background street, of a black boy being chased by his angry father (presumably), who in turn is being chased by his angry wife brandishing a rolling pin. More than just some incidental comedy, this seems to suggest a level of everyday family tensions and potential violence. How are we meant to read this sight gag, while Spirou sings the praises of the wealthy and throughly democratic neighbouring nation, seemingly a ‘paradise on earth’?

Fantasio’s air pilot pal Bosco (a nod probably to Jijé‘s biography in comics form of Don Bosco) berates an African cargo worker at the airport, calling him “A species of horse chestnut fed on coal from the Tropics!” and a “lymphatic asshole!” The incidental character Odongo gets his revenge by not loading the crates of corned beef, in which Spirou and Fantasio are hiding to be smuggled by Bosco’s plane into Urugondolo. Odongo is a cypher, typified by his laughter - “Niark! Niark!” and simplified, ungrammatical language. Another fleeting joke here shows Bosco in the cockpit with his black co-pilot who is puzzled by Bosco’s smirking face and asks, “Have I got black on my nose?”

This sort of “comedy” seems really questionable and to be perpetuating insidious racism. Perhaps most surprising is that no one at Dupuis, then or now, seems to be at all bothered by it. What were Chaland’s intentions? To be ironic? To point out the idiocy of racism at that time? As Woodrow Phoenix asserts in my new book Comics Art , “Is a lack of any racist intention enough to allay concerns about comics artists making such retro-chic revivals today?” According to Phoenix, “continuing to use this symbol now is the worst kind of thoughtlessness.”

For better or worse, the rather chaotic unravelling of Coeurs d’acier was cut short after 23 episodes and left open-ended. Where might Chaland have taken his story? The last episode on September 16th 1982 hurriedly sums up the threats and intrigues yet to come, showing our player on board the high-speed atomic train en route to Urugondolo’s proud capital Babela (complete with Babel-like tower), the ‘City of Diamonds’, while in the wings lurk leopard-costumed tribal menaces and an army of robot warriors. Bocquet analyses Chaland’s predicament, ‘caught in the crossfire in the Spirou war’ being waged between two creative teams, Broca and Cauvin in one corner, and Tome and Janry in the other, both with their supporters. Money was the official reason for letting Chaland go. Why pay him double the standard rate, especially a Parisian without any strong ally within the editorial team?

The book includes an interesting photo of Yves in the market of Mbanza Ngungu in March 1986, taken by his wife from a trip to Zaire. Before leaving Chaland writes ‘Leaving for the Congo’ in his diary. While he was away, he sketched a follow-up storyboard in biro in a lined notebook (below), as Spirou, Fantasio and a young woman continue their quest for the ‘Heart of Steal’, now in the jungle, where they are assaulted by a leopard skin-covered female from the Anyoto tribe. As it turned out, a different sequel was soon in development by Chaland, assisted by writer Yann ( nom-de-plume of Yann le Pennetier). They put the plucky pair on board an F52 atomic plane returning from their African trip. A robot, like the initial version of Coeurs d’acier, hijacks the plane and crashes it in the savannah near the fabulous city of robots, where scientists are trying to mechanise humanity.

Getting support for this latest sequel, Chaland and Yann prepared designs and in all ten pages were worked out, some of them fully inked though none appear here. We do get to see some lovely fresh concept sketches on board the F52 plane and a tantalising proposed cover (below). Unfortunately, this version also became caught up in more editorial manoeuvres and business machinations. Chaland and Yann would eventually return to this idea for their sophisticated Freddy Lombard story F52 in 1989.

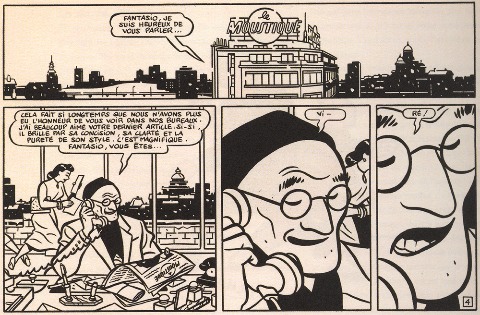

Meanwhile, at the Dupuis offices, Jean Van Hamme was appointed director general and editorial director combined. Unconvinced by their second Spirou proposal, he urged them to bring both characters back to Brussels. In this next plot, those robots were once more the focus with the leopard-men lurking in the wings. This next proposed story was titled Moustique Journal and with encouragement, Chaland and Yann cracked on with it. The finished original 2nd and 4th pages are reproduced here. The 4th (below) shows reporter Fantasio getting sacked from the newspaper; sadly. more or less the same would happen to Chaland and Yann and this project also bit the dust. Bocquet untangles how this happened and reconciles conflicting memories with Chaland’s own diaries.

These days at Dupuis, variant versions and flashbacks of Spirou are part of the character’s more multi-faceted, official fictional life, opened up by Emile Bravo’s 2008 Spirou album set in 1938, for the 70th birthday, and continued, for example, in Yann’s yarn drawn by Olivier Schwartz, Le groom vert-de-gris, once mooted for Chaland, or this year’s apocryphal Spirou: Sous le manteau (‘Spirou Under the Counter’) by Alec Séverin, fictional adventures supposedly produced in secret under the Nazi Occupation - Dupuis’s history being re-written and published by Dupuis itself!

It’s a far cry from what was possible back at the dawn of the Nineties. Chaland had still not abandoned his initial version of Coeurs d’acier, even though Dupuis seemed to have written off his strips and left them uncollected in book form. It was not till 1990 that Champaka were unusually lucky to get special permission from Dupuis to officially reissue and collect in a limited edition of 1,350 copies all the Coeurs d’acier strips, with the addition of a salmon-pink second colour designed by Chaland’s wife Isabelle Beaumenay-Joannet.

Still eager to complete their story, Yann rewrote what happened next and concocted an ending in a second companion volume. Chaland provided a dozen new illustrations, although he was constrained by Dupuis from drawing any new Spirou or Fantasio likenesses, so he could show the pair only disguised throughout in their leopard skins. It’s a bit of a shame but perhaps not a surprise that none of these supplementary illustrations appear in this new Dupuis book. Champaka released a ‘definitive’ version of their two volume set, compiled into one in 2008 and putting the 23 strips into four-colour printing, again by Isabelle Beaumenay-Joannet.

Ultimately, Chaland never fully realised his dream of Spirou. On July 18th 1990, following a car accident, he tragically died. He was 33, far too young. He had so much more to achieve and astonish us with. Re-reading Coeurs d’acier, I can’t help wondering if he was almost speaking to us through Fantasio when he has him say, in a brief existential mood in the 13th episode here, “I must leave future generations a vast and useful oeuvre!”. Chaland’s oeuvre proved to be not as “vast” as it ought to have been, yet it undoubtedly remains “useful” to generations of readers and creators as an ongoing pleasure and inspiration.

Posted: December 15, 2013