Will Eisner:

The Human Spirit

So what are your plans for your old age? Slow down a bit, work fewer hours or not at all, maybe retire to Florida and relax by the pool? That’s what Will Eisner could have chosen to do back in the late Seventies. Eisner’s long, hardworking career had lifted him up from the cut-price comicbook sweatshops of the Thirties to a relative financial security of the profits from his perennially reprinted Spirit stories and his successful informational comics company American Visuals Corporation. He’d made it and could look forward to an easy life.

But as he approached 60, Eisner found a renewed passion and curiosity about what comics might become next, how they might be evolved into a different sort of literature. Instead of coasting into his twilight years, he used his financial security to pay for one of the most valuable things in anyone’s life - time out. He could drop everything for several months and concentrate on a deeply personal project, working ‘on spec’ with no advance, client or contract in mind, no collaborators or assistants. Eisner was flying solo, creating for himself.

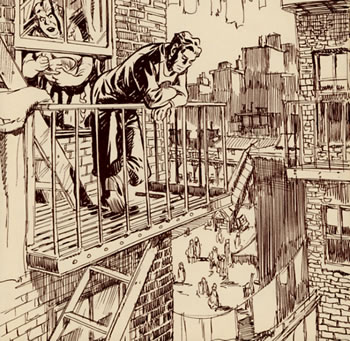

In these circumstances, the blank page presented a very different canvas to him. Why merely repeat everything he’d done before? The number of pages at his disposal, the style and composition, the subject matter and treatment, were all his to choose. Instead of relying on the standard hard black outlines and tightly-ruled panel borders typical of comicbooks, he moved into drawings in washes and tones floating on the page. As for his stories, he followed the sound advice of ‘write what you know’ and took himself back to his childhood experiences growing up in a Bronx tenement through the Depression.

Hawking around this strange, eccentric quartet of rather sad period vignettes of Jewish life, Eisner did not find a publisher straight away. A Contract With God probably baffled most publishers. Finally, in 1978, his 60th year, he found a small outfit, Baronet Books, willing to risk it. They published it in hardback, without a dust jacket, and at the same time in a larger print run in paperback. How was this puzzling illustrated book going to be described to punters? Eisner suggested putting the term ‘graphic novel’ on the paperback cover.

Now, Eisner did not invent this term or the concept. It had already been coined as long ago as November 1964, in a small circulation comics newsletter solely for members of the Amateur Press Association when American fan and critic Richard Kyle suggested it as a way to describe his vision of a "long form comic book". Eisner commented on this to Time.Comix journalist Andrew Arnold, "I had not known at the time that someone had used that term before." He seems to have arrived at the term quite independently.

Eisner was also well aware that there had been many attempts to create a ‘graphic novel’ before his. One of his own formative influences was the powerful wordless picture story God’s Man by Lynd Ward which he had marveled at in 1929 (recently reissued by Dover Books). He told Arnold, "I can’t claim to have invented the wheel, but I felt I was in a position to change the direction of comics."

That is exactly what Eisner did. It’s diverting but ultimately fruitless squabbling over who ‘invented’ the first graphic novel. What matters s that Eisner’s stand had a major, meaningful impact on his fellow professionals and their successors, from Jack Kirby to Art Spiegelman. He was committed to reinvigorating the medium’s ambitions, to build upon the adult themes pioneered by the maverick young geniuses of underground comix, to aspiring to literary seriousness and this inspired others to follow his example. It became his mission for the rest of his life - crafting book after book, teaching, traveling the world, interviewing his peers, theorising about the medium, presenting the profession’s Oscars, the Eisners.

What kept Eisner going for over 20 years? He once explained it to Neil Gaiman. "He told me about a film he had seen once, in which a jazz musician kept playing because he was still in search of The Note. That it was out there somewhere, and he kept going to reach it. And that was why Will kept going: in the hopes that he’d one day do something that satisfied him. He was still looking for The Note."

When I started writing my column ‘Novel Graphics’ for Comics International, I simply had to start with Eisner. After his death on 3rd January 2005, I had to return to him. His last two works are among his most challenging and heartfelt and reflect his preoccupations during his latter days - a deepening interest in his Jewish heritage and a desire to confront the roots of persistent anti-Semitism.

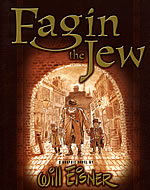

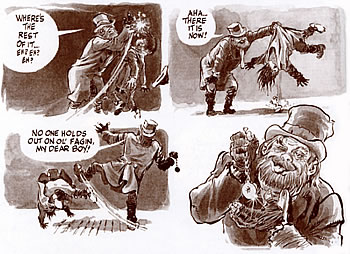

One of the most negative stereotypes of Jews is the notorious rogue Fagin from Oliver Twist, written by Charles Dickens. George Cruikshank illustrated him for the book as a typical swarthy hook-nosed character, adopting a common Jewish caricature relied on by artists before him. Eisner felt this image was all wrong and had contributed "to further reprehensible stereotyping of Jews by bigots throughout history". To address this in Fagin The Jew (published by Doubleday) he researched the period and reinvented Fagin’s appearance and fleshed out his back-ground to reflect history more accurately.

Eisner understands the necessity and convenience of stereotypes in comics and uses them himself, but he hoped that in his Fagin he could arrive at "a more truthful stereotype". You will never look at Ron Moody’s portrayal in Oliver! in the the same way again.

For his final masterpiece (posthumously published in 2005 by W.W. Norton) Eisner took on perhaps the single most pernicious source of anti-Semitism, The Protocols Of The Elders Of Zion. The Plot reveals the twisted history of this Russian forgery that purported to reveal a Jewish conspiracy to rule the world. As early as 1921 in The Times, these papers were proven to be false, and yet Eisner was stunned to discover they are still believed and propagated online to this day. To counter them, he wanted to create a work, "that would be understood by the widest possible audience."

His search for that elusive Note drove him right to the final day before his heart surgery. In The Plot he has left us a rigorously researched and urgently necessary graphic documentary. This plea for truth and an end to racist lies is his last, lasting gift to us.

The original version of this article appeared in 2005 in Comics International, the UK’s leading magazine about comics, graphic novels and manga.