Wallace Wood:

Against The Grain

A notice on his studio wall warned any potential imitators that, "There’s is only one Wally Wood and I’M HIM!"

The last few months have seen a spate of handsome reissues of the late Wally Wood’s work, from DC’s T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents Archives and Dark Horse’s M.A.R.S. Patrol to deluxe editions of The King Of The World, the first volume in his trilogy The Wizard King, and Lunar Tunes, a previously unpublished satirical roller-coster created shortly before his death in 1981 and out in June from Vanguard Productions.

So now’s a good time to look back at this unique and complex maverick.

Wood repeatedly rebelled against the exploitation and shortsightedness of many editors and publishers in the comics industry, as well as the stifling constraints of the Comics Code Authority. For example, years before young superstars like Jim Steranko and Barry Windsor Smith first rejected the poor conditions and nonexistent royalties and rights available to mainstream comic book creators in the early seventies, Wood had walked away from Stan Lee’s Marvel Comics in 1965 after his short but brilliant revitalisation and redesign of Daredevil.

We can only imagine what wonders Wood might have created for the House of Ideas, had he been allowed more credit and stayed on. Instead, Wood soon came to have no illusions about either Marvel or DC, damning them both as "fascist states. I use them when I need them, but they have no power over me."

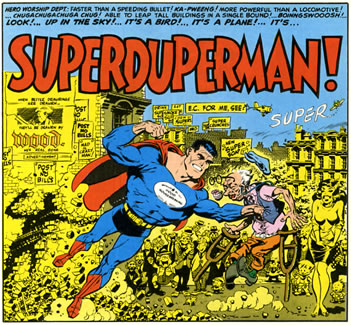

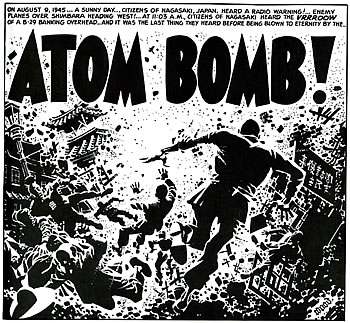

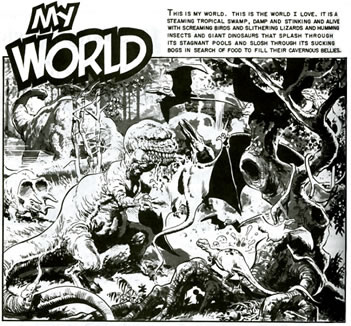

Both companies were very different from the supportive atmosphere at EC Comics in the Fifties, where Woody shone notably on the classic Harvey Kurtzman MADs, also now available as DC Archives, and their horror, SF and shock titles. After Marvel, Wood pursued different paths in his constant desire for the freedom to create his worlds on paper in whatever way he wished, and to control his work’s publication, distribution and rewards. Sadly, his grand, optimistic ambitions would eventually fade or collapse.

In 1966 Wood arrived at the bold solution of publishing his comics, and those by others, for himself in the seminal witzend magazine, and later from 1978 in his Tolkin-esque graphic novel epic The Wizard King. I can’t help wondering how different this all might have been, if only Wood had been able to enjoy some of the benefits now provided to creators with the direct sales market.

Wood had so many missed opportunities. Just imagine if he had been able to edit a new adult comics magazine from James Warren to be called Pow!, to illustrate the comic adaptation of the movie Alien, to take over Hal Foster’s Prince Valient or have a hit syndicated newspaper strip of his own, or to work for Heavy Metal magazine or on full-length adult albums for leading publishers in France. None of this came to be. Former assistant Al Sirois may be right when he suggests that Wood had a "subconscious urge to defeat himself."

Throughout his life, Wood struggled with debilitating migraines and depression, not helped by his around-the-clock sessions at the drawing board to meet deadline demands and an alcoholic addiction that led to excessive drinking binges. Faced with failing kidneys and being hooked up to a dialysis machine, in 1981 he took one of his guns and shot himself. He was only 54.

Suicide so often remains a mystery, but I think there are insights in the fine Two-Morrows biography Against The Grain: Mad Artist Wallace Wood. Editor Bhob Stewart talks with Wally’s elder brother Glenn, who reveals that he was taller and admired as more manly by their father than Wally, the quiet artistic type, slight of build.

Stewart quotes a telling anecdote told to Nick Cuti about how, when Wally was in the Paratroopers, he wanted to impress his father by visiting him in his military uniform. "His father, a foreman of the lumberjacks, turned around to his lumberjack friends, started barking orders and had them running and scrambling all over the place. Then he looked at Wally and nodded his head, as if to say, You see, you may think you’re something special, but you still aren’t as good as your old man."

How much might the life long lack of paternal approval have affected Wood? Might it account, at least in part, for his fascination for the machismo of guns, for his workaholic fervour, for his bottling up of his emotions, only to be released when he was drunk?

Perhaps no volume will ever completely encompass the man and the artist who was Wally Wood, but Against The Grain does convey the multifaceted creativity and complex character of one of the great visionaries in American comic books. Seek out his work as it returns to print, but reflect too on his struggle. I feel that however wonderful the legacy he left us truly is, Wood’s fate remains a tragedy of squandered potential and troubled personality and an indictment of the old-style industry practices that refused to accommodate them.

THE COMPLEAT CANNON

BY WALLACE WOOD

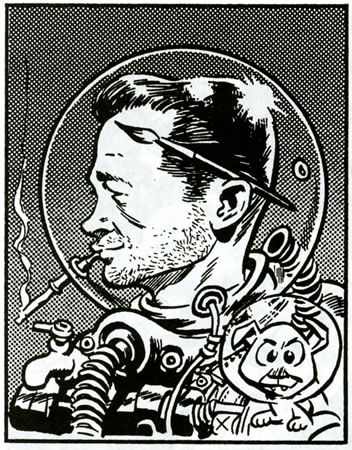

I’m sorry, but great artwork alone, no matter how great, is never, ever enough in comics. That’s one of the biggest fallacies that continue to hold this medium back. Fans of ‘good’ drawing in comics, usually highly finished and illustrative, seem to be able to blind themselves to a comic’s other woeful inadequacies. No wonder the uninitiated can’t see what we see in them, once they start reading them. Take this first ever, oversized compilation of all 130 of Wally Wood’s tough guy superspy Cannon full-page strips, published by the military newspaper Overseas Weekly from 1970 to 1973. Wood and his crew of assistants are on solid form throughout, the art has all the clear composition, contrasts of light and shadow, and slick finish and letratones he was famous for, but the content is disturbing.

The backcover copy tries to laugh it off in some postmodern spin as ‘a raucous, politically incorrect masterpiece’, selling it for its ‘naked girls, more naked girls, and still more naked girls’. In his intro, historian Jeff Gelb picks this up, quipping ‘What’s not to like?’ , but finds little more to say in its favour. Strip away his detailed context-setting of the Sixties spy genre and his gushing for Wood’s babes and brushstrokes, and even he can’t avoid concluding that ‘...it was ultimately just schoolboy fantasies, or completely enlisted men’s fantasies.’ Let’s be blunt-although Wood was undisputedly one of the greats of American comic books, not everything he and his studio produced cries out for reprinting as some lost classic.

Sexy girlie strips as a troop morale-booster were nothing new. The advances of British Forces during World War 2 could be correlated precisely to how much lingerie Norman Pett’s Jane lost in the line of duty in the Daily Mirror, while the femmes fatales of Milton Caniff’s Male Call stirred many a lonely G.I. Joe. But there is no charming striptease or intelligent glamour here. Every week is a parade of exploitation, degradation, torture and rape of women, all of them identically perfect, pendulous and brainlessly available, which they were not, in the army or in reality. The most sinister aspects are first that someone in the military actually wanted U.S. soldiers to read this misogyny manual as entertainment, perhaps inspiration, during the darkest, final years of the Viet Nam war, after the My Lai massacre, and secondly, that Wood was willing to oblige.

As for Cannon, he is the ideal agent, cannon fodder, so brainwashed, first by the Reds and then by the CIA, that he has no emotions, no humanity and takes the copious amounts of female flesh around him for granted. Like his phallic name, he is a cold, hard, lumbering killing machine on wheels with balls of iron. He promotes a depressingly persistent, damaging role model for maleness. In some ways, Wood himself was not unlike Cannon, emotionally shut down, uncommunicative and difficult to get close to. Michael Gilbert pinpoints the problem in his insightful short Wood biography in Alter Ego Vol 3, No 8 (TwoMorrows, 2001), "If Wood’s drawings grew cold and sterile over the years, was it any wonder? He was a passionate man, but afraid to show it. In time, it even became hard to display his emotions on the page."

Wood was a recluse, a workaholic, an alcoholic, a husband in three failed marriages, self-destructive and in the end suicidal. The Compleat Cannon closes with a photo circa 1980 of Wood ‘goofing off’ in his studio, drinking a beer, brandishing a gun and wearing a Nazi helmet. It makes no mention that a year later he would shoot himself in the head, but then that grim reality wouldn’t exactly fit in with the book’s marketing of Cannon as ‘escapist fantasy.’

Wood had always wanted total control and copyright of his creations, but by the time he got them, apart from self-publishing, his only moneyed clients were the military and smut magazines and his heart was not in them. Still, he was stubborn and he had bills to pay. Without a strong writer or editor like Gaines, Feldstein, Kurtzman or Stan Lee, he was going solo, toughing it out, doing his duty, a battle-weary sergeant in command of gifted but unquestioning enlistees. The saddest part may be that this soulless, twisted machismo was the best he could muster. I’d much prefer to remember and re-read Wood at his peak.

The review of Against The Grain: Mad Artist Wallace Wood appeared in 2005 in the pages of Comics International, the UK’s leading magazine about comics. The review of The Complete Cannon appeared in 2003 in Comics Forum.