Tintin & Snowy:

A Boy & His Dog

Every morning, millions of males put a dab of gel on their hair at the front and make a little quiff to give it a bit of lift and character. They might not realise where that look started from, but they’re actually turning themselves into the big-hearted blond reporter Tintin.

Like Magritte and the saxophone, Tintin is a Belgian original with universal appeal. While America was exporting costumed musclemen with superpowers to save the day, Belgium sent forth a spunky youngster in plus-four trousers with a dog called Snowy. It’s his dot-eyed ordinariness and open, almost blank personality that have helped so many readers to imagine themselves in his shoes trotting the globe and righting wrongs.

His creator, Hergé was only 21 when he packed the boy and his dog off on their first assignment to The Land of the Soviets in 1929 in the children’s weekly supplement of a Catholic Brussels newspaper. Tintin soon grew so popular in his homeland, that the following year thousands of his young readers flocked to the capital’s railway station to greet him, played by an actor, returned from Russia.

Over the course of fifty-four years, Hergé would complete only 23 albums in all and leave a 24th unfinished. His body of work may not be huge by some standards, but twenty years since his death it still sells phenomenally in over fifty languages. In 1992, French-language sales alone topped 3 million copies, and last year, finally, the series was officially published in China after years of pirated editions. When Tintin in Tibet was translated as Tintin in Chinese Tibet, Hergé‘s widow, Fanny Rodwell, close to the Tibetan people, insisted that the whole print run be pulped and replaced by the unaltered title.

Tintin first travelled to the New World on his third mission in 1931, but somehow his brand of multi-cultural awareness has never made his books click in America, where annual sales reach only 100,000 copies. That may be not so much because Tintin is too European, but more because he is too much a citizen of the world.

All that could change with Steven Spielberg closing a deal to direct a live-action movie version. Spielberg started this project going twenty years ago, not long after Hergé‘s death, when he visited Brussels and was knocked out by Hergé‘s original artworks. Unhappy with the scripts, Spielberg withdrew to the role of producer and François Truffaut, Jean-Jacques Beineix and in the end Roman Polanski were suggested as director. With little progress, the option lapsed by 1987, but now seems back on track.

So which album, or albums should Spielberg adapt? There are some gems and frankly some disappointments, so here’s a beginner’s, and maybe a director’s, guide.

The very first album from 1930, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, exists only in a black-and-white facsimile edition, one of a series in English from Last Gasp. It’s a period piece that can be enjoyed for Hergé‘s unrefined exuberance, unsubtle propaganda and to see the start of the character.

Of the other early albums, Tintin in The Congo is the worst, rife with the questionable values of its time, showing Africans as simpletons, animal life as expendable, and Tintin as the great White Man bringing ‘civilization’. Tintin in America and Cigars of the Pharaoh get progressively better, but Hergé‘s first masterpiece was The Blue Lotus in 1934.

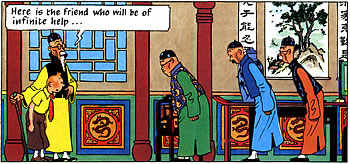

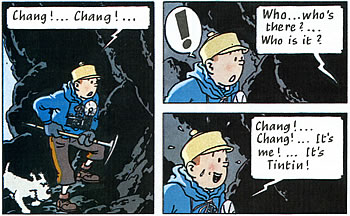

For this, Hergé met Tchang, a Chinese student one year his junior, who helped him create a much less stereotyped, and more sympathetic portrayal of China under invasion from the Japanese. Hergé put Tchang into the story as a boy who is saved by Tintin and befriends him. From here on, Hergé thoroughly researched his locations and tried to ground Tintin in the real contemporary world.

The next five albums range from The Black Island, a popular romp set in Britain, and King Ottokar’s Sceptre (the source of the British bookshop chain Ottakars), with its thinly disguised critique of Fascist leaders ‘Musstler’, to The Shooting Star, whose lamentable anti-semiticism can still call Hergé‘s ideology into question.

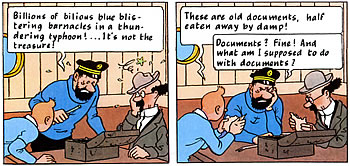

His trio of two-parters are among his very best, allowing for more complex plotting and characterisation. The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure are a perfect ‘jumping-on point’ as they reveal Captain Haddock’s past and introduce the delightfully deaf Professor Calculus. The South American and moon-landing stories come equally recommended.

The rest of the series ranges from solid to sublime, apart from the tired final album. If you read only one Hergé story, it must be Tintin in Tibet, his pinnacle, in which Tintin’s search for the missing Tchang in the Himalayas mirrors Hergé‘s own life crisis and his failure to find the real Tchang. In fact, he did eventually locate him and they were reunited in 1981.

Other favourites are The Castafiore Emerald, an escalating comedy of errors set in Haddock’s country house, and The Red Sea Sharks, a political exposé of gun-running and slavery.

Tintin was 75 in 2004. Don’t wait till the movie, and don’t take Tintin for granted. It’s definitely not just kids’ stuff. It’s human stuff and that’s why, at its best, it’s about as great as comics can get.

Posted: January 8, 2006The original version of this article appeared in 2003 in the pages of Comics International, the UK’s leading magazine about comics.