Superheroes:

We Can Be Heroes

A boy on holiday in 1960s Llandudno, Wales. A squeaking spinner-rack groans with American soft-porn mags, but my gaze is fixed on those colourful comicbooks stuffed into the lower racks. Haphazard distribution means never knowing if I’ll find the next issue, much less ones from months before.

Picking out some Marvel titles, I turn to the last page, hoping that maybe this issue would be complete. But over and over, I found only continued stories and put them back, choosing DC, Charlton, Tower instead. Stan Lee himself recognised this problem when around 1971 he introduced a rule that, stories should be complete in one issue.

The idea didn’t last very long.

But that was how early American comicbooks worked during their formative years in the 1940s. Superheroes largely operated in short, inconsequential stories and within their own isolated worlds, blissfully unaware of any others of their type, unaffected by any previous story’s events. The status quo would always be restored by the end of every case, ready for the next. That way, each issue could serve as somebody’s first encounter with a character. Every story was an event.

As early as November 1941, barely six months after he had broken into comics, Otto Binder (1911-1974) was already a writer with a vision. His life and career are revealed in Billy Schelly’s fascinating 2003 biography Words Of Wonder. In an article in the SF fanzine Sunspots under the Binder brothers’ joint pen-name Eando (as in "E and O" for Earl and Otto) Binder, he speculated about the future of this fledgling artform.

"The trend in comics… is toward longer-length stories and more detailed plotting. A year ago they were slam-bang, plotless action. Today, gradually, you find human interest, twists, detailed characterisation. A magazine is soon to come on the market - Young Allies - which presents a complete book length story in 60 pages, divided into six chapters. In these, the keynote is still rapid action, but less so than before. By a process of evolution, another year from now may see 60 page stories comparable to your favourite novelettes by science-fiction authors, with picture telling the story instead of [just] words."

In his way Binder was envisioning the graphic novel years ahead of its time. His prediction proved correct, because it was not long before a few writers tried bringing their heroes together and involving them in longer tales. Binder himself was given the chance in 1943 to script a two-year, 25 part serial, Captain Marvel And The Monster Society. He deliberately modeled this continued story on the cliffhanger movie serial starring the Big Red Cheese showing in cinemas on Saturday mornings. For his super-villain he came up with the wild idea of the mysterious Mr Mind who turns out to be a little green worm with spectacles and a voice amplifier.

The entire saga came to 232 pages, easily America’s longest continued and complete comicbook story at that time. It was compiled into a book only decades later in Britain, edited by cartoonist Mike Higgs and published by Hawk Books in 1989 as a large-format hardback in a limited edition of 3,000 copies.

Like the stuff of myth and fairytale, this Captain Marvel classic still has a freshness and wit that made it a natural choice for Jeff Smith of Bone fame to reinterpret as his debut graphic novel for DC. The tale is so much lighter and simpler than most of what had filled superhero comic books in recent years.

Binder’s prophecy of "longer-length stories and more detailed plotting" came true in superhero comics, from Gardner Fox’s Justice Society Of America yarns of up to 58 pages, to those book-length "imaginary stories" like Jerry Siegel’s Death Of Superman. But the concept really took off during the 1960s Marvel Age of Comics, when Stan Lee and his artistic co-creators wove an interconnected soap-opera ‘universe’ that became a template for DC and other publishers.

The pleasure for devotees, and the drawback for newcomers, was the increasingly complex baggage of ‘continuity’ which accumulated over time like barnacles around these companies’ never-ending, licensable properties. Within continuity, it seems there can be no real change, only "the illusion of change". Even death itself became temporary. This partly explains why in 1986 Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had to fabricate their own characters in Watchmen, because they planned to show the splattered blood of a dead superhero on the first issue’s cover and opening page. Back then, nobody was allowed to do those sorts of things to established, copyrighted crime fighters, even to second-stringers like the Charlton bunch. It is a minor miracle that DC allowed Watchmen to stand alone and to end, dismissing talk of prequels or spin-offs.

Naturally, there’s a strong appeal to many creators to work on the ‘real’ bona fide superstars, not least their earning power, but I want to focus on some of the post-Watchmen graphic novels about new superheroes. It’s a relief to start a fresh with accessible characters unencumbered by continuity, and see them being taken where no protected big-name archetype could ever go, except maybe in some imaginary What if? of Elseworlds tale, where anything can happen but nothing matters.

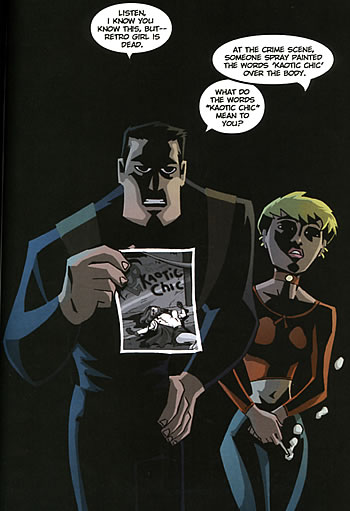

A heady cocktail of police procedural and cape drama, Powers (Image/Marvel Icon) is shaping up well as Brian Michael Bendis and Mike Avon Oeming take more risks, pushing their alien Superman substitute to madness and genocide and giving Deena Pilgrim powers of her own.

Kurt Busiek‘s Astro City (Homage) continues to be own of the more perceptive takes on the genre, by showing, in the author’s words, "Not what it would be like if superheroes existed in our world, but what it would feel like if we could wander through theirs."

Taking a similar cue in his two-book Love Fights (Oni), Andi Watson charts the love life of superhero comic artist Jack, jinxed after the superhero whose adventures he draws becomes embroiled in an alleged love-child scandal. It’s a charming blend of manga and Euro styles, romance and spandex, with the coolest super-feline since Streaky.

A familiarity with comics lore, if not a degree in the subject, would benefit anyone reading Michael Chabon‘s The Escapist (Dark Horse), the hero from his Pulitzer prize-winning novel. Still these short, sharp adventures cleverly pastiche different periods and styles into a playful rewriting of four-colour history, along similar lines to Alan Moore’s referential Supreme (Checker) or Tom Strong (DC/ABC).

More accessible to neophytes might be Brian K. Vaughan‘s Ex Machina (Wildstorm) smoothly drawn by Tony Harris and Tom Feister, in which the world’s only superhero, The Great Machine, alias Mitchell Hundred, retires from crime-fighting to get elected as New York’s Mayor. In this intelligent post 9/11 intrigue about his four years in office, Mayor Hundred’s powers over all machinery come in handy in the game of big city politics, but how long will he be able to keep control of his space-born gift? This had me hooked from the outset.

It’s clear that, outside of the giant playpens of Marvel and DC, superheroes can proliferate as never before, from Kirkman and Ottley’s ‘typical’ American superteen Invincible (Image) to James Kochalka‘s badmouth wannabes Superf*ckers (Top Shelf).

Posted: July 29, 2007The original version of this article appeared in 2005 in Comics International, the UK’s leading magazine about comics, graphic novels and manga.