Simon & Kirby’s The Sandman:

A 1940s Revival

If you want to work for mainstream American comics, especially the Big Two, Marvel and DC, you usually don’t get the chance to start on some concept totally of your own. No matter what brilliant, utterly original ideas you might propose to them, to get accepted into the hallowed fold, these publishers are much more likely to take you on if you can revive and revamp one of their existing properties first. You have to prove yourself, do your “tour of duty” on their in-house characters, before you can be allowed to branch off into something more of your own devising. It’s happened over and over. Alan Moore was set to work on the languishing Swamp Thing and turned it around completely. For their debut, Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean had to prove themselves by sprucing up the largely forgotten Black Orchid. Grant Morrison started by dredging up Animal Man, for goodness sake. Even crime fiction’s best-seller Ian Rankin this summer winds up writing a Hellblazer yarn for his audition.

This insistance on keeping company-owned characters, even if only their names, in currency is not some recent policy; it goes back to the Forties and the industry’s early “Golden Age” years. For instance, it happened when hot twenty-somethings Joe Simon and Jack Kirby jumped ship from their soaring success with Captain America at Marvel Comics, or Timely at that time, and came on board the more established, somewhat classier outfit Detective Comics and All-American Publications, who would combine into DC. Joe Simon told Doug Headline in 1984, for the introduction to a French black-and-white hardback reprint of Sandman, why they switched to DC: “The money! They offered us twice as much! And when we got there, they didn’t know what to do with us.” For their first assignment, rather than bank on some completely new creation of their own, Simon and Kirby offered to adopt the two weakest features in Adventure Comics, ripe for replacement, and remodeled them with their distinctive panache. Manhunter was the lesser of this pair, abandoned by them after only eight episodes. But the bigger hit by far, and the very first story to see print by them at DC, was The Sandman.

Now to clarify, this Sandman is not Neil Gaiman’s celebrated Morpheus from The Endless, although that is yet another example of a name owned by DC being given a fresh lick of paint and literary depth and unexpectedly emerging as a triumph. Nor was this the very first Sandman, a pulpy crimebuster, like The Shadow but in a gasmask, who had gone out of style by 1941. The Sandman which Simon and Kirby inherited had only been introduced three months before, in Adventure Comics #69 (December 1941), as a standard costumed superhero, a fairly blatant imitation of Batman, complete with with his own Robin, known as Sandy the Golden Boy. It says something about the ordinariness and lack of faith in this approach that it was so quickly headed for the chop. But Simon and Kirby instantly turned it around, injecting much of the vigour and imagination that had energised their previous dynamic duo, Captain America and Bucky.

It’s fun to speculate what might lie behind their very first story for their new employers, “The Riddle of the Slave Market”. While their former boss Martin Goodman looked nothing like the bald, leering villain of this piece, the “fat, swaggering slave trader” Pete Bragg, their whole theme of enslavement and exploitation, of wealthy prisoners bidding for Bragg’s slaves to take their place in prison or on chain-gangs, of Sandman in chains put onto the auction block and of course emerging victorious, after giving Bragg a good pummeling, all this might have vented some of their frustrations with Timely/Marvel. As Kirby recalled, “We were actually kind of glad to be out of there.”

There have been sporadic reprints of a few of these Golden Oldies, but 12 of these stories, including the first two, have never been reprinted before. So this archive edition of Simon & Kirby’s Sandman finally compiles into one hardcover both Sandman stories from World’s Finest Comics, #6 and #7 and all 23 tales from Adventure Comics, together with all the front covers. To round this off, there’s a re-run of Simon and Kirby’s one-shot refurbishment of the character from 1974, notable for dropping Sandy and bringing in two loveable monsters, Brute and Glob, as his nightmare assistants. Kirby drew four more with writer Michael Fleisher, though it’ll be quite a time, I expect, before these get the Archive treatment.

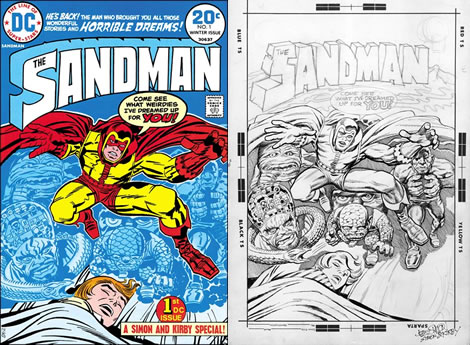

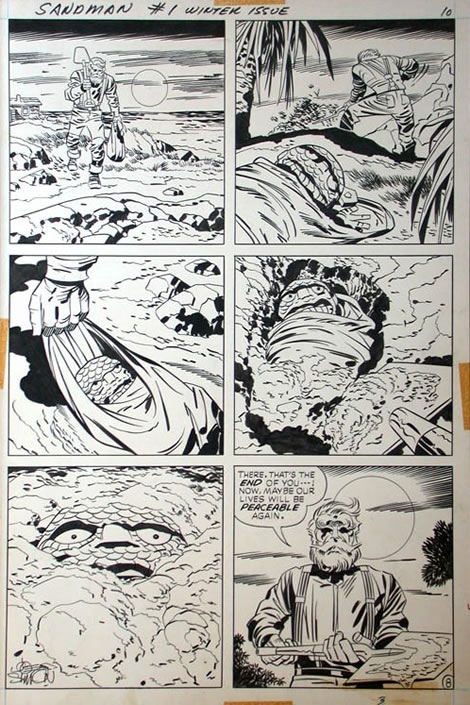

The 1974 Sandman revival:

(left) Final cover, Jack Kirby inked by Mike Royer;

(right) Original art for an unused cover, Jack Kirby inked by Joe Simon;

(below) Original Kirby/Royer art from Sandman #1, 1974.

Going back to the Forties, working within the constraints of ten-page tightly plotted yarns, Joe and Jack devised some nuttily boistrous thrillers, with bonkers criminal schemes like hiding bells in an heiress’s hat to drive her mad, dressing up as rampaging Vikings, building a deadly high-tech forest as a refuge for crooks, or staging a second coming of Noah and his ark with gangsters disguised as animals. Tying in to the Sandman’s folklore roots, they spin out many variations on sleep and dreams, insomnia or narcolepsy, nightmares and premonitions, and more noble aspirations or innocent hopes, like one’s boy’s fondest wish for his first pair of long trousers (perhaps a childhood memory for one or both authors?). Their more inventive fantasy sequences, where our heroes can enter and interact with the dreamworld, typically wind up slipping into the slam-bang punch-ups that end most of these tall tales.

What is hardly developed, however, are Sandman and Sandy’s personalities, backgrounds or their bigger potential. Unlike Batman and Robin, they have no cool gadgets, only their trusty wire-poons to whisk them across the city, their “Sandcar” (aka “Sandmobile”) is no Batmobile, and they have no Batcave or recurring, grotesque rogues’ gallery. And later in the run, from a stockpile produced under pressure before Joe and Jack had to go into service, the quality of art and story noticeably drop off as other studio hands have to finish the job. The shifting spectrum of their collaboration means that some Simon and Kirby stories look a lot more like Simon than Kirby, and one or two, notably the lacklustre ‘Courage a la Carte’, almost like neither of them. In fact, clearly missing from this one is the handiwork of another master of comics, the distinct lettering craftsman Howard Ferguson, famed for his flourishes of brush script words and stylish folds and scroll and penant effects in captions.

Even so, almost from the start, Simon and Kirby’s creativity swiftly elevated the series to front-cover billing - and for four issues the Simon & Kirby byline makes the cover too. One of their greatest covers ever is included here, Adventure Comics #84 which breaks the fourth wall by having Sandman pointing out at the reader and shouting “Nobody leave this magazine… a crime has been committed!!!” Interestingly, as World World 2 wore on, these covers diverged from representing the stories inside to became patriotic propaganda posters, showing our heroes manning artillery, urging our boys into battle, and sneaking up on Jerries and Japs. That said, Sandman and Sandy never tangled with the enemy inside. Simon and Kirby did draw the duo in five other short episodes (a mere 6 pages each, the last one only 5). These formed part of the multi-chapter, full-length adventures of the Justice Society of America in All Star Comics. The first of these, in All Star #14 (reprinted in 1997 in All Star Comics Archives Volume 3), was plotted by Gardner Fox and Sheldon Mayer and written by Fox. They send Sandman and Sandy to Greece to help an uprising against Nazi invaders. By the third of these, Sandy has been dropped and Sandman scuppers more Germans on his own. Sandy is back for the fifth of these interludes although he’s forgotten in the rest of this JSA case.

The splash-page from Adventure Comics #74.

Click the image above to enlarge and compare

the restored page (left) to the original printed version (right).

Note the renaming of side-kick ‘Sandy’ to ‘Candy’ in the 2nd caption!

Now there’s no avoiding the problems of how to faithfully reprint these fading timepieces. DC Comics’ usual Archive policy until recently has been to adapt the artwork by stripping out all of the original, often poorly printed and dot-patterned colours to get back to a black-and-white line version and then add bright, sharp colours back in. This restoration, often on smooth or shiny white paper, usually requires some retouching of the black artwork and has none of the palette and texture of the period newsprint sources. This reprinting uses another approach, scanning in the pages directly from the printed comic books and then applying Photoshop to clean up all the text balloons and captions and remove any paper colour from the gutters between the panels. The choice of paper is cheaper, thinner, closer to the stock of the comics. Fans and critics will debate which of these systems is preferable. It does depend on the print quality of the original materials and on the scans made of them, especially as there could be misregistration or printing faults, both in evidence here. This may give a sort of authenticity, but there is an odd clash on the eyes here, as the whites and yellows of the text boxes and bubbles stand out much more than the muted colours in the panels.

A further issue is the reduction, by about seven per cent, of the artwork to fit today’s narrower standard comic book format. Golden Age comics were that bit wider, so the shrunken pages here have lots of extra blank space at the bottom and butt very closely into the spine. Looking back at an original 1944 Sandman episode in my collection (though not a Simon and Kirby one, sadly), there used to be a good comfortable half-inch border all round the artwork area.

There is a “third way” to reprint comic books, perfectly exemplified by Abrams’ oversized collections Art Out Of Time, edited by Dan Nadel, and the forthcoming Toon Treasury of Classic Children’s Comics, edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly, and their precision scanning and restoration of high-quality sources onto soft, thick, light-cream paper. It’s also possible to compare and contrast the version of ‘The Villain from Valhalla’ in the DC edition with another in Titan Books’ handsome compendium of The Best of Simon and Kirby, nominated for an Eisner Award. Harry Mendryk, the expert restorer on this book, has been able to enlarge the pages by a whopping twenty-one per cent, letting us really dive inside these compositions, and has carefully replaced all the colours to avoid them blurring or shifting out of alignment. True, his new colours are more strident, his whites as bleached as the paper, but it offers another quite effective and attractive solution.

There is, however, another not insignificant downside to this DC hardcover. I found some haphazard restoration of the text. It is a plus to have all the balloons and captions cleaned up for clarity of reading, but nobody seems to have proofed this work by Digikore and Rich Keene for errors, often involving mistaken letter shapes, especially ‘G’s for ‘S’s. For instance, on page 32, panel 5, Sandman addresses his sidekick Sandy as “Gandy”. On page 34s splash page, Sandy becomes “Candy”. On the splash page on page 55, “The Adventure of the Magic Forest” becomes “The Magic Forget”. And on page 92, where a tricky escapologist is dug up from his buried trunk, Wes Dodds says, “Hmmm ... it’s looked all right!” instead of “locked”. There may be more, but I didn’t spot them through the rest of the book, and thought maybe that was all. But no, in one final glaring blooper, on the last page of the 1974 Sandman #1 reprint, in the book’s penultimate panel, the caption reads, “Then, Bandman blows his sonic whistle…”. “Bandman”? Someone should have “blown the whistle” here!

These could be simple errors or automated spell-checks, which any editor ought to have spotted, but I can’t help wondering if mischief, even deliberate sabotage, lie behind them, as a protest at perhaps the poor payment for all these Photoshop chores? It might sound a bit mad, but I decided to correct my copy with some black pen and White-Out.

Frankly, at one cent below forty dollars, this is not a low-cost item and it has its share of flaws. But it’s still way less than the price of finding every one of these rarities in their original mustiness and will hopefully lead to future DC collections of The Boy Commandos (there’s enough for two volumes) and The Newsboy Legion. In the meantime, Titan Books’ Official Simon & Kirby Library is lining up further samplings, starting in autumn 2010 with The Simon & Kirby Superheroes, a massive and unmissable 480-page double-sized omnibus of their superheroes, including Captain 3D, an unpublished Stuntman story and their first superhero collaboration, The Black Owl from 1940. Following this will hopefully come single volumes of their romance, horror and crime output.

Kirby would have been 92 on August 28th this year, but he died in 1994. Happily, Simon is very much alive and busy, completing his autobiography, The Man Behind The Comics, also from Titan, and no doubt pleased to see his collaboration with Kirby being rediscovered and reappreciated by readers today.

Posted: September 6, 2009