Robert Crumb:

Interview

Forever tied to cartoon characters such as Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural, Robert Crumb is too easily pigeonholed as the sex-obsessed taboo-breaker, unchanged since his late-1960s heyday in the underground comix movement. It’s true that Crumb’s role in the iconography of America’s drug-fuelled counterculture was pivotal, yet he remained an ambivalent outsider to that era.

Now sixty-eight and living in the South of France since 1993, Crumb has long shown more multifaceted qualities, from his candid, autobiographical self-deprecation about his lusts and fetishes to his satirical puncturing of smug-liberal and conservative-reactionary tendencies. He also extols the raw vitality of past masters of blues, jazz, country and other popular music through biographical comics, CD covers, card sets and his own music-making. Not forgetting his partnership with his wife and cartooning peeress, Aline Kominsky Crumb, the pair writing and drawing themselves on the same page to commemorate their ‘dirty laundry’ (starting with the two-volume Dirty Laundry Comics series, published in 1974 and 1978, and carrying on through recent regular contributions to The New Yorker).

Crumb is also a serious, studious reader and compulsive explorer of his outer and inner life, devoting four years to adapting the Book of Genesis into comics, published in 2009. The entirety of this magnum opus is part of the first ever major museum retrospective at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, opening on April 13th and continuing till August 19th. It will bring together over 700 drawings, sketchbooks and more than 200 underground magazines, arranged chronologically around ‘Crumb’s obsessions: love, hate, fear of women, music, a raw look at the modern world and introspection’.

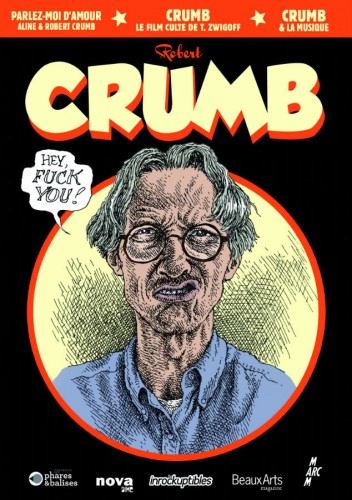

To coincide, Editions Paris Musées are publishing a 272-page catalogue, in French and English, with 220 rare and unpublished images and essays by Sébastien Gokalp, Joann Sfar, Jean-Pierre Mercier, Todd Hignite and Jean-Luc Fromental. Also re-released this year from Edition Cie des Phares & Balises is Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb documentary movie on DVD (see cover above) with some interesting bonus extras including a new interview by Jean-Luc Fromental, Stéphane Beaujean’s documentary on Crumb and Aline Kominsky’s French compendium of their collaborative comics, Parlez-Moi d’Amour (coming out this autumn in English from Norton & Knockabout as Drawn Together), and another film about Crumb and his passion for music.

Also highly recommended is the first approved biography of Crumb, a 232-page paperback with 11 illustrations, written by Jean-Paul Gabilliet and published in French by Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux. I have been enjoying reading this exemplary, thorough and riveting account, which hopefully will soon have an English translation. Of particular resonance is Gabilliet’s coverage of Crumb’s “meteoric rise” in the Sixties US art world, “the first in all of the American underground”. Gabilliet points out that, as early as 1968, Crumb was already being honoured in his first solo exhibition of his comics, opening November 7th that year at the Peace Eye bookshop on New York’s Lower East Side, run by Ed Sanders and “at the time the New York equivalent of San Francisco City Lights”. Then in 1969, Crumb’s original artwork was being exhibited simultaneously in two group shows, at the Phoenix Gallery in Berkeley, California in a survey entitled The New Comix, and in New York’s Whitney Museum in the exhibition Human Concern/Personal Torment: the Grotesque in American Art. He has had plenty of other significant art shows since, of course, but that said, this imminent Paris exhibition is of an unprecedented scale, profile and prestige.

I caught up with Crumb in his Paris apartment, the night before he was due to fly with his wife to a comics convention in New Delhi at the country’s second Comic Con. Here’s the full free-flowing interview, parts of which were edited and published in Art Review 58, April 2012 with a new one-page comic by Crumb and Kominsky, published in English for the first time and shown below. I’m lucky to be going to the Private View in Paris this Wednesday April 11th, joined by Robert McNab, who produced the BBC’s excellent Arena documentary on Crumb, and by Australian pal, graphic novelist and fellow Crumb aficionado, Bruce Mutard. I’ll be reporting back further.

Paul Gravett:

With this big Paris show, you’ve come a long way from selling those first copies of Zap Comix from a pram on the streets of San Francisco in 1968 [Biographer Gabilliet reports that this sales system was conducted for one day only, February 25th 1968, and that in total 82 copies were sold - 22 by Robert and his eight-months-pregnant wife Dana, 12 by publisher Don Donahue, and 48 by Donahue’s friend Mimi, aka Marilyn Jones McGrew]. What was the turning point when you realised the art world had accepted you?

Robert Crumb:

There was no sudden moment, it’s been a gradual thing. I really think when the Terry Zwigoff Crumb film came out in 1995 - even though the art world considers itself above mass media - that had a big effect on my reputation. It put me in some other class. That was one thing. I don’t understand why they chose me as the cartoonist to do that with. They’ve dragged me up into the pantheon of the fine artists, for some reason, I don. I don’t understand how it happened, but my work goes for a lotta dough now. Nothing like Cy Twombly. His scribble gets several million while something I’ve worked on for six months might get $50,000. I don’t know if the money is a degree of how ‘fine’ the art is, but I am still not that ‘fine’.

You’re not making work intended for the gallery wall.

That’s right, it’s all done for print. I tell this over and over again to these guys from galleries and museums. To have it on the wall is just a curiosity. Very few people are going to put a comic page on the wall of their house.

In terms of selling original comic book art, the truism is that what sells is covers and splash pages, big images, not sequential panels.

There is a world of connoisseurs of comic art and they know who’s good and who isn’t and they will buy comic pages. Some of them will put pages with panels in on the wall. But generally, they put them in big flat drawers and they get them out and look at them like that. They buy in quantity, a whole story can be 25 or 30 pages of art. It doesn’t work to isolate one page on the wall…

Other cartoonists have made the crossover to fine art, but they often minimise or deny their pop culture roots. I’m thinking maybe of Robert Williams or Raymond Pettibon.

They both always aspired to see their stuff in galleries. Robert Williams couldn’t wait to see his stuff in some New York gallery. He was pissed off for decades because he was only known in underground comix.

I wondered if you feel you have a long-form graphic novel still in you.

That’s a tough question to answer…

Is there still more story material unplumbed from your life, like your family history tale ‘Walkin’ the Streets’ in Zap Comix 15?

Plenty. It could go on endlessly with that. I might do more of that. Hard to say at this point.

Have you made art specifically for galleries?

I made a couple of statues and stuff like that. I fooled around with a few paintings a little bit, not much. I don’t really ever do it with the intention of having gallery shows.

Any regrets that you never got an art school education?

Well yeah, I think if I was young and I’d gone to art school, it could have saved me a lot of trouble learning anatomy and stuff, with life drawing classes. That could have been very helpful actually. When I have to draw anatomically correct like in Genesis, I struggle with that a lot.

Have you taken life drawing classes?

Very little. I draw from life off and on, but I’ve never really got down and done a lot of life drawing classes.

You’ve mentioned the difficulty growing up in America of getting good art books, for example about Otto Dix.

You could get books about Picasso, Renoir, Cezanne and all the Impressionists, Van Gogh, all the usual suspects. But I never saw Otto Dix till Robert Williams showed me a little tiny book of about 3 by 4 inches of Dix’s paintings which completely stunned me. That sort of stuff was hard to find. I came out of the pop culture background basically, TV and comic books were what I grew up with. And my brother Charles was completely obsessed with comic books and kind of pushed it on me. I liked to draw but he was a storyteller. His main interest in comics was telling stories. Then later we’d be drawing comics together and wrote stories so I ended up a comics storyteller. So that’s my background.

It was only later that I discovered bit by bit first the world of old-time illustration, I am very interested in that. And only fringely interested in most fine art. I got to liking those German guys like Dix and Grosz and I liked Salvador Dalí and other surrealist stuff like that. I like a lot of Outsider Art, primitive and strange stuff by crazy people. The thing about the fine art world is they have this pyramid, this hierarchy, and it’s very rigid. It’s breaking down a little bit but it’s according to how much money you can get for something. I don’t buy into that. I had zero interest in abstract expressionism, starting with the post-war American artists.

After Philip Guston’s break with abstraction starting in 1967 and his first show following that in 1970, the two of you seemed to be suddenly exploring similar territory.

Yes and completely independently of each other. Guston started doing that strange, funky, cartoony-looking stuff around the same time that I did. I didn’t see his stuff till way later but I saw the date, he seemed to tap into this murky layer of the collective subconscious around the same time that I did. It makes me wonder if he was taking LSD like I was, I don’t know.

Was Guston aware of you?

I don’t know, I’ve never read anything about that at all. His break with abstraction happened rather suddenly, it seems, so I tend to suspect that he might have taken psychedelic drugs, as a lot of people were taking them in those days. People were taking them, cultural and intellectual types, before it became illegal in America. He tapped into something very odd and unlikely, and so did I.

You have been living in France since 1993. Do you feel remote from America and US pop culture, which were such an important part of your infuences, your creative mulch? Is that a problem?

I don’t feel remote from it, because in the modern world you can get anything, any movie, any book, music, any comic, you can read English language newspapers and magazines. The only thing I am remote from is the day-to-day life of the United States and when I lived in America, a lot of my work is a reaction to day-to-day life there. So that’s not there anymore and I don’t know what effect that has. When I got back there - I go back once or twice a year - after I’m there for a couple of weeks, the old contempt and disgust with America comes back over me again, probably even stronger than when I lived there. I can have contempt and disgust in France too! But in America, it’s so strong, it’s sick or something!

What do you dislike about France?

It’s a general disgust with humanity. I’m in Paris right now and we just came back from going on the Metro and you look at humanity and it’s just appalling, appalling out there! (Laughter) I’m no better, I don’t think I’m superior or anything. If I look in the mirror, I have the same reaction.

At least the French respect artists and creators a bit better?

No, the French have such a bullshit attitude about art. The bullshit is so thick here, it’s ridiculous. The French government supports art, there are a lot of art subventions, I don’t know why, they give a lot of money. Lots of people get on this bandwagon and make such terrible, terrible art, all over France.

What do you think of comics-inspired French fine artists like Herve Di Rosa?

Yeah, kinda interesting. And the other guy, Robert Combas. But there’s not enough nutrients in it for me. Guys like that are jockeying for position in the art world. Outsider artists, who aren’t looking for a place in galleries, to me are much more authentic and genuine, crazy people, working in isolation, that to me is much more interesting. In the world of comics where I come from, ninety-nine per cent of it is uninteresting to me, it’s vacuous and slick.

It’s that rare one per cent that makes all the difference, when you find it.

Yeah, it’s the same in the fine art world.

Among the reviews of your Book of Genesis, Michel Faber in The Guardian wrote that it “comes across as the fruits of indentured drudgery.”

It sure felt like indentured drudgery when I was working it, maybe he’s right! (Laughter)

Some people wanted Genesis to be racier and spicier…

Mm’yeah… We’ll see what posterity has to say about it, I have no idea. I can’t judge it. I gave it my best shot. It was a huge amount of work.

You added some vital visual elements that were not conveyed in the Biblical texts themselves.

Sometimes you have to, because there’s so little information to figure out what it looks like if you visualise it, so you have to make some stuff up. But the main point of that book is not ‘R. Crumb does Genesis’ but just here you have a comic of the entire Book of Genesis, every word. Any number of competent illustrators could have done it, it just happened that I did it. People are used to seeing something else from me, more strange, wacky, personal, whatever, and they’re a bit disappointed that it doesn’t have those elements to it. Basically, it serves its functional purpose of a comic of the complete Genesis, every word, and I did try to do as readable a version as possible. That’s never been done before. No other comic has done any part of the Bible, Old or New Testament, that’s complete like that. That was impressive to me, that it’s never been done.

I had a look at some other versions from the past of comics based on the Bible, and every one that I saw, they had put dialogue into the mouths of characters that’s not in the book! I found this one comic, set at the beginning of Genesis, they only got a quarter of the way into it and they gave up on it, probably in the Seventies, and they had Eve saying, ‘Gee, I hope Adam likes this Apple!” As I said, I think any competent illustrator could have done what I did. It wasn’t a big stroke of genius or anything. I was the only person with patience to finish the whole thing. Drudgery, that’s right!

You were toiling like a monk working on an illuminated manuscript.

Oh I love that stuff, medieval illuminations. That reached its peak in the 1400s, just before the invention of printing. It’s wondrous to look at. It’s narrative illustration. They try to keep it kinda simple and straightforward and not have any pretensions.

Michel Faber ended his review by saying: “I can’t help believing there must be more spirit in the old devil than this tome suggests.”

I’m 68 now. I think he’d love that stuff I did back in the Seventies and Eighties more. I got it out of my system, I don’t know.

So was Genesis partly a way to vent anything from your Christian upbringing and rejection of religion?

No, not at all. It started with a scholarly interest in ancient Mesopotamian culture. I’d been studying it a lot and reading other early Mesopotamian myths like the Gilgamesh story and Babylonian stuff. Then I started looking more closely at Genesis because it’s related, as I said in the book’s notes, some of the stories are the same. And I thought maybe I’ll try illustrating this.

I think Joe Sacco’s books on Palestine are incredible. There’s a guy who really deserves a lot more attention than he gets. Incredible amount of work he puts in. He went there and lived with those Palestinians, he put himself on the line and did this beautiful comic about that. I think part of the reason he is not getting more credit is that he makes Israel look really bad.

You did some early reportage drawings in Harvey Kurtzman’s Help! magazine (above).

I went to Bulgaria for Harvey Kurtzman and I did a thing about Harlem. I’ve also done some collaborations with Aline that were kinda like reportage. We went to the Cannes Film Festival and that Fashion Week for The New Yorker.

What are you digging into now?

In the last few years, I’ve got so deeply involved investigating scandalous shit that goes on in modern business and culture. It’s very difficult to interpret in comics, I’m trying to figure it out. There’s not a lot of action or humour, it’s serious, grim shit. You could get your ass in trouble doing that, too. I remember when I did this thing in the Seventies, ‘Frosty the Snowman’, where I had him being this revolutionary who throws bombs at the Rockefeller mansion and shortly after that was published, the Internal Revenue Service came after me.

I remember, you got a big tax bill around that time.

Yeah and I believe they wanted to neutralise me. In fact, I heard from a guy I met recently who used to work for a security agency, and he said, ‘Oh, Crumb, I heard that you had been neutralised!’ I worry about that a little bit, you know! If you dig up underneath the surface and publicise it on a large scale like I would do in my work, the forces of power…

That’s presuming you can find a publisher for it…

There are publishers who would probably do it, though they would be smaller publishers. Since it’s my work, they would probably do it. It’s true, with a big publisher, it would be difficult.

Hopefully, it is getting less easy for these sorts of people to hide, with the internet around.

Yeah, absolutely. But we also have in the modern world what I call friendly fascism or PR and propaganda that is so sophisticated. Perception management has reached such a level of sophistication, if you get underneath that and break it out, they would really come down on you. They’ll get their journalists, their people, after you, to discredit you. The financial and corporate worlds, the worlds of science and medicine, all of it is involved. Science and medicine is really a big one, it’s scary. It’s so grim, if you want to tell people what’s really going on.

It’s mostly narrative, I just have to figure out how to do this. There’s two approaches, either tell the stories straight, name names and draw pictures of these people, of the evil guys involved. Or you can put it in some kind of terms where it’s slightly disguised in a fictitious story, like [the John Le Carré novel] The Constant Gardener and tell it that way. That would probably lend itself more to comics, a noir approach. I don’t know, I’m not sure. I haven’t worked that out.

What do feel about going to india?

It’s my first time, Aline’s been there twice before. We got invited to this comics festival in New Delhi and it’s only the second year and they’re only inviting four people from the West, as far as I know, me, Aline, Gary Groth, publisher from Fantagraphics, and Chris Oliveros, from Drawn & Quarterly. I asked them how do you even know about my work? Are the books distributed there? They said they found out about us on the internet. I don’t know what they are going to think of my work. They have certain conservative and religious traditions, but at the same time they have those crazy old termples with the most lascivious carvings on them (laughs).

I guess when you were approached about this major retrospective opening in Paris, you could have said no?

Yes, but that would seem very ungrateful! So I told them I’d do but I just don’t want to have to do lot of work on it myself. And they said, ‘Yeah, yeah, fine’. But then of course it ends up being a lot of work anyway. They want this, they want that, confirm these lists, tell them who took these photos back in the Seventies.

I gather most of the artwork comes from various collectors, but do you still own all of the Genesis originals?

Yeah I do.

Would you eventually sell them, all together?

Yeah, hopefully. I think it should be sold all in one piece.

This year also brings the English version of Parlez-Moi d’Amour, translated as Drawn Together, due from Norton in the USA and Knockabout here in the UK, collecting all your collaborative comics with Aline Kominsky, from Dirty Laundry to The New Yorker. Do you still get a buzz from making your comics together with Aline?

Yeah, those are easy to do, those comics with Aline. She’s just a fountain of this Jewish stand-up comedian humour that comes out of her. I just have to give her a lead line and she just takes off. With her, you have to trim down the dialogue to fit it all in a page. We kinda work it out together, it’s pretty even-steven. She just pours out all this comedy dialogue and I have to in some way impose some structure on it sometimes, but it’s kinda even, both of us fifty-fifty. We’ve done a new twelve-page story for that Drawn Together book, which would never have made it into The New Yorker, we showed some explicit sex stuff in it. And now we’re doing these one-page comics every two months, each on a different theme, in this hip French women’s magazine Causette [see example below]. We have a version in English and in French but we haven’t found an English publisher yet. As far as I know, the husband and wife thing is totally unique. I don’t know of any other in comics, I think we’re the only ones who ever did that in comics.

Fans of your comics are not necessarily fans of Aline’s.

The crudeness of Aline’s drawing is a big problem for a lot of comics readers. Most of the people who really like Aline’s work are from outside the comics world. Within the comics world, fans, who are mostly boys, guys, they like that slick drawing. Aline’s stuff is just too crude. It’s completey in harmony with her writing and they fit together seamlessly, but juxtaposed next to my work, it’s somewhat clashing and jarring. That’s part of the whole meaning of the thing, it’s the difference between us, our drawing styles, two different people. But the funny thing is that some people are so un-visual, like at The New Yorker, some people thought that I drew the whole thing. They had no idea, they didn’t look closely enough!

I heard about The New Yorker cover not running your cover about gay marriage.

I quit working for The New Yorker after that. The editor David Remmick just wouldn’t give me any kind of explanation of why he wasn’t using it. I didn’t expect an apology, but at least an explanation. He just sent me back the artwork, nothing, no comment, months later after, according to Françoise Mouly, the cover went back and forth without using it and then finally he decided not to. She said she doesn’t know why. I can’t work for somebody under those circumstances, when they don’t tell you why they rejected something. How are you going to know, if you continue to work for the guy, what his criterion is? And then you’ve got to second-guess him.

The thing is he is really spoiled because he’s got artists falling over themselves to do covers for The New Yorker. You go into Françoise Mouly’s office and the wall is covered with dozens of rejected New Yorker covers. Françoise is doing a book of them, there are so many of them! She got permission from the editor. The New Yorker is not participating in it but they’re not stopping it. Rennick is just spoiled, he doesn’t think he has to be that respectful of artists. They’re so eager, waiting in this big breadline outside the building to draw covers for him!

Speaking of New Yorker covers, did you see the Sempé exhibition in Paris?

He doesn’t interest me that much. He’s too minimal for me. He’s one of those Fifties-Sixties minimalist guys. I rarely go to exhibitions. I just get a book on the subject (laughs). It’s such a big pain in the ass to go to those places. I just recently discovered an English artist I’d never heard of before, L.S. Lowry. I love that stuff, factory towns of the Midlands, great work. Apparently, he was a sophisticated guy, had money and moved in circles of culture and intellectuals, but he has this almost primitive style. I was talking to this couple from the Manchester region, she’s from St. Helen’s, about this book called Industrial Town, all about that area, that I had read, and she told me how she was from there, she had the book. Then she asked me if I’d ever heard of L.S. Lowry and I said no. So I got a book on him, it’s great stuff.

I hope you enjoy India.

I’m sure it’s going to be education, I should see it once. I suggested they invite Gary, because I was going to go to Australia last year [for the Graphic Festival at Sydney Opera House] and they’d invited Gary, who spent weeks preparing this 90-minute powerpoint panel with me and then he couldn’t use it because I cancelled the Australia thing. So when this India thing came up, I called Gary and asked, ‘You want to go to India?’ and he said ‘Yes’. He’s dreading the plane trip because for him from Seattle it’s like twenty hours. Gruelling.

Are you still making music?

Yeah, I play music, mostly by myself, once in a while with a band.

I enjoyed your BBC Radio 3 series a few years back, R. Crumb’s Sweet Shellac produced with Robert McNab. Is anything going to be done with it?

Yeah, nice guy, I like him. He made the BBC Arena documentary. I don’t know if the BBC even bothered to save that stuff, I hope so.

I suppose you’ve not stopped collecting…

Oh yeah, I’m still hunting. I hope I can connect with someone in New Delhi who’s got 78’s. I have some Indian 78’s, they’re great, fabulous music from the Twenties and Thirties, even into the Forties. Not Western-influenced at all and it’s so exotic, it’s hard to tell what’s art music and what’s folk music.

Aline & Bob In ‘A Couple Of Perverts Not In Provence’

Aline & Bob In ‘A Couple Of Perverts Not In Provence’

Click image to enlarge.

Posted: April 8, 2012

An edited version of this Article and Interview originally appeared in Art Review magazine, April 2012. With huge ‘mercis’ to Lora Fountain.