Pushwagner:

Soft City in Milton Keynes

It was a beautiful summer’s evening as my train pulled in from London. My first time in Milton Keynes. Staring out of the windows of the taxi from the station, en route to the MK Gallery on August 8th to give a talk on graphic novels, I was immediately struck by the straight, wide, tree-lined boulevards, not intended for pedestrians to cross, and a strong sense of my being dropped inside a square grid system of streets, resulting in the odd spaciousness and separatedness of buildings and the necessity of getting around this rectilinear web by car. With most of the buildings - offices, shops, residential - only a couple of storeys high (nothing higher please than the church), I felt a lack of landmark architecture and orientational icons.

Stepping out of the taxi, wandering through more grids of broad, pedestrianised rows of restaurants and shops, in search of the gallery, I felt as if I was an identikit extra, an architect’s prop, dropped into a town planner’s dreamscape, a master plan of urban design which put the car and the driver first and foremost. To someone, this probably all looked like the ideal, orderly city of the future on paper and miniature models back in 1967, when Milton Keynes became Britain’s last designated ‘New Town’.

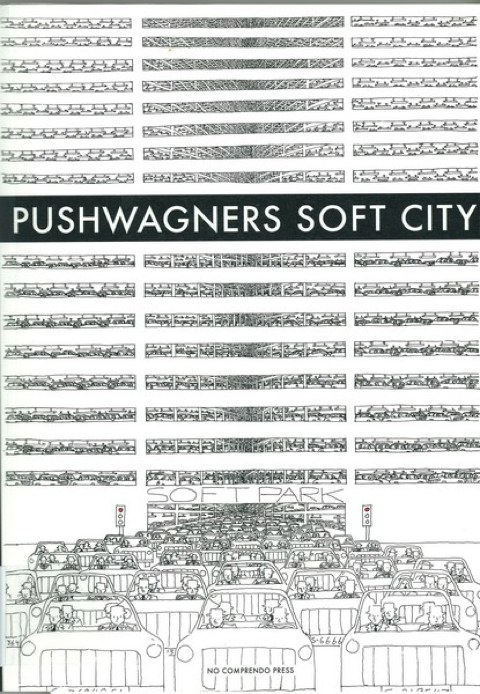

Now, 45 years on, it seems oddly fitting that it is Harriton Pushwagner (real name Terje Brofos, born 1940 in Oslo) who has brought me to Milton Keynes to visit his first British exhibition. No disrespect, but being here seemed as if I had stepped inside the story and world of Soft City (above), the Norwegian artist’s foundational opus, which he worked on in fits and starts in Oslo and London between 1969 and 1975. I couldn’t help feeling like one of the hapless, hopeless, office-worker drones in their Magritte-esque bowler hats. Perhaps my limited first impressions of Milton Keynes had been coloured by my re-readings of this 154-page graphic novel. It all seemed so ‘soft’ here, so thought-out, as if I was walking inside somebody else’s thoughts, somehow subtly controlling. As Pushwagner warns, ‘Who controls the controller?’

A parable of disillusionment, a prophetic warning told in the single cyclical and perhaps very final day of a compliant, unquestioning father and mother and their curious baby, Soft City was lost and unseen for years. It was only in 2008 that it finally saw print from No Comprendo Press, as a lengthy court battle ensued which finally won him back his creator’s rights to the work. It’s only recently that Norway, and the wider art world, has acknowledged Pushwagner’s significance and relevance to our present-day economic crises and our supposed connectedness through proliferating screens of televisions, computers, cameras, smart phones and tablets.

As it turned out, The MK Gallery was hard to miss, because its windowless facade had been eye-catchingly adapted into a blow-up of one of Pushwagner’s Pop Art-like images of a woman’s thick-lipped, open mouth, her tongue protruding like a red carpet, the sliding door opening automatically, as if she is swallowing us whole. My first port of call was to see all of the original artworks from Soft City, Pushwagner’s epic which is among the 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die.

These drawings are displayed in black-framed, waist-level vitrines (above), angled as if on their original drawing board. Browned, aged, frayed, fragile, the 42 x 30cms pages convey the thinking, working and feeling poured into them, from the shaky, all-too-human ink lines and the vanished figures and elements corrected and deleted in contrasting bright white-out, to his use of drawings on other pieces of paper, glued down and often extended and completed, other collage elements, and in places black-paper, for example for a large cut-out silhouette of the baby Bingo. None of this, of course, is visible in the pristine printed graphic novel in black-and-white with spots of colour; this was artwork made for reproduction not exhibition.

The sumptuous exhibition catalogue shows an unused image (part of a proposed cover?) of the baby smiling on the controller’s screen, with the lettering ‘SOFT’ above as if made of sugar cane with colourful stripes. There follow 79 pages from the book, switching papers from the glossy, classy stock of the rest of the book (and the rest of Pushwagner’s non-comics art) to a pulpier matt finish. Perhaps to avoid making the book version redundant, they omit quite a few pages, but retain enough of the themes and thrust, the opening and closing, to appear complete. Interestingly, there are differences between the artworks on display and what got printed. For example, when our worker first leaves the flat to head for work and meets his counterparts, all doing the same, in the hallway, he has him say “How do you do?”, though this is missing on the original (apart from some white corrected spots towards the back of the image which may well have been small speech balloons).

Fortunately, all 154 pages are on view and allow visitors, if they choose, to read the complete, untruncated story. It’s a tour de force of graft and application, as there’s no photocopying shortcuts here. He draws the figures and furniture in each room, adjusting the perspective to reflect correctly how they would be seen, from below, directly opposite, and above. Repetitive, meditative, compulsive, this is a labour of conviction, rooted in Sixties and Seventies counter-culture politics and in graphics such as those of Saul Steinberg, Robert Crumb, Jean-Michel Folon or Milton Glaser, clearly fueled considerably by drugs but also by a drive to communicate. Perhaps, however identical his city-dwelling citizens appear, they have at least been drawn individually and distinctly. The tale ends with Bingo’s parents taking their soft sleeping pill, leaving him awake, clutching his teddy bear, and crying, unheeded, “Oh! Oah! Oaah!” into the full-moon night.

Nearby, one whole high wall of the MK Gallery is fill with 34 silkscreen prints in black, grey and pink, again in heavy black frames, the full 1980 suite entitled A Day in the Life of the Family Man (above) - the catalogue offers only 14 of these. Many of these parallel, rework or revise images from Soft City but avoid any reference to this and its ‘soft’ world, and any dialogue or narration. Among other changes, baby Bingo has a robot toy, a recurring item in Pushwagner’s other art, which is also found here operating the Controller’s control systems. Pushwagner also moves with the times to portray more women among the workforce heading to the office, although he still leave only women to be child-minders.

Another arresting, comics-like wall brings together his Apocalypse Frieze (above) as he always wanted it to be presented, his seven large, feverishly detailed paintings housed and unified within an imposing, dark-wood multi-frame. Dizzyingly intricate, hallucinatory, vertigo- and nausea-inducing, these magnify his determined assault on capitalism, war-mongering and suppression of the individual to epic scale and impact. This culminates in a Dante-esque self-portrait of one head whose interior is filled with infinite buildings of human beings, packed like slaves or sardines inside their box-like rooms, the buildings soaring out of sight above and below. And in the midst of all this, like the DNA spiral, endless humans parade past in circles, again both upwards and downwards, disappearing. So much for any notion of the power of the individual.

There’s plenty more to take in from early travel drawings to recent bright, hand-coloured ‘digital graphic artworks’, as well as screenings of a 2010 colour animated film based on Soft City, and in the first floor reading space a 2011 Pushwagner documentary directed by Even Benestad and August B. Hanssen (below). The catalogue includes some useful analyses as well as the highlight, a free-wheeling, interview-based account by the artist of his own eccentric, often self-destructive trajectory, a haunted, often thwarted life, which makes revelatory reading. There’s one minor transcription typo or memory lapse among the comics he mentions reading around 1947: ‘Steel Canyon’ is of course Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon, while ‘Killjoy’ is a mystery to me (Steve Ditko’s wacky Charlton superhero by that name would not appear till 1973).

Pushwagner discloses a lot in his account. At one point he was reduced to selling his drawings on the London Tube, and had to drop his price from 25 to a mere 10 pence each. As he worked on Soft City in London, it’s no surprise to find some English aspects to it, such as bowler hats (once de rigeur for all civil servants) and references to ‘telly’, even the name ‘Bingo’. In one passage he explains, “...finally finishing it was a very good feeling. I had people coming to see it and being astonished, many people from the London scene of the time: Stevie Winwood,... Ian Dury, Peter Townsend, plenty of others. Still to me, it was all for my daughter. I was in love with this child, she was the meaning of my life. And so, of course, the fact that I lost the book before it could be published, before the work had been seen by more than a very few people, was a blow so strong that I couldn’t quell the effect of it. I was stunned and, once again, I was inoperative.”

Its rediscovery and rescue, its restoration both in book form and now in this touring exhibition in the UK, Norway and the Netherlands, confirm how timely and timeless Soft City was, and still is. Prepare to be astonished.

Update April 24th 2018:

Norwegian visionary artist and graphic novelist Pushwagner - whose Soft City book was reissued in 2016 by New York Review Comics, with a cover designed by Chris Ware (below) - died April 24th 2018, aged 77, as reported on this Norwegian website.