PG Tips No.41: My Best Comics & Manga of 2014:

Year in Review

There’s much more to comics than long-form, single-volume graphic novels (much as I really enjoy them and set out my personal Best of 2014 of them from Britain, North America and Europe which you can read about here…). So in this part of my Year in Review, I’ve picked out my favourite, most interesting superhero-related comics, translated manga and books about comics.

MY TOP TEN SUPERHERO COMICS OF 2014

1: ‘Hide the face and you hide the race.’ America’s superhero comics tradition has long been dominated by white male characters and in recent years the issues surrounding under-representation and misrepresentation within this field have been debated and to some extent addressed, but the gender and race imbalance is still undeniable. In The Shadow Hero (FirstSecond), Chinese-American Gene Luen Yang and Singaporean Sonny Liew decide to tackle the dearth of Chinese leading heroes by looking back to one all-but-forgotten superhero from the ‘Golden Age’ of the Forties, when this genre was fresh and trying any twist that might give a publisher the next Superman or Batman. Blazing Comics put a new character on the front cover called The Green Turtle, but he failed to catch on and vanished after five issues.

In the book’s afterword, Yang discusses how the artist/creator of The Green Turtle was Chinese, named Chu Hing. Based on the limited information and on speculation about his creation, it is convincingly argued that Hing wanted to show that his new crimefighter was himself Chinese, introducing the first Asian American superhero, but the publishers would not accept this. In protest at having to show his creation as yet another all-white American, Hing came up with the brilliant yet bizarre ploy of never, ever showing The Green Turtle’s whole face below his nose, only his Batman-like mask covering the upper half of his head.

Considering how much superhero comics rely on the eye-catching appeal of cowls and costumes and how comics generally use clear facial expressions to engage the reader, Hing’s strategy ran counter to many of the medium’s strengths and may well have been a big factor in his hero not proving popular with readers - as if he is like a turtle whose head spends much of its time hidden within its shell! To see for yourself how throughly he managed this constraint, you can read all five of Hing’s tales in the Green Turtle Archive here on the amazingly useful Digital Comic Museum website.

The hero’s very first cover appearance (above) is noticeably unusual, showing an extreme close-up of a bald baddie being throttled on the ground by The Green Turtle, standing astride him and visible only from the knees down. Inside, his tall red collar often obscures his profile, while much of his body is shrouded beneath a large blue cape decorated with red and yellow edgings and a turtle symbol, with a yellow line version reversed out of black on its underside. In addition, an odd turtle-shaped black shadow with yellow eyes and red lips often fills the background and signals his presence on the pages, often seeming to grin mischievously at the reader. As required, The Turtle also obscures his own face, for example behind a raised arm or fist. It all becomes a distinctly strange way of choreographing a comic, where your lead protagonist can never show himself to us, complicating how we identify him, and identify with him. It’s inevitable effect is to force the artist to portray, and the reader to view, almost all the action from behind the hero’s body, looking over the shoulder and cape, thereby putting the spotlight predominantly onto Hing’s caricatures of the villainous Japanese themselves, the targets of the artist’s vehement anti-Japanese propaganda (below).

True, we do see the Turtle full face and full frontal on the cover of the second issue of Blazing Comics, but the Grand Comics Database does not credit Chu Hing as its artist. Our hero is also shown with a junior sidekick, who his young pal Burma Boy does not become inside. On the opening title panel of the third issue’s story, Hing shows The Green Turtle facing forward but keeps half his face in shadow - as it turns out, this version represents a double of Green Turtle who is a secret Japanese impostor. His fourth adventure shows him a few times with his face entirely in shadow, suggesting his mask now covers his whole face, as if making him faceless and raceless. And the story ends again on the unanswered question, ‘But who is The Green Turtle?’

Seventy years later in The Shadow Hero, Yang and Liew cleverly give an origin and rationale and finally answer Hing’s pregnant question. The Green Turtle narrates how, as the son of Chinese immigrants to ‘San Incendio’, he was cajoled by his mother into becoming a superhero after she was rescued by the local superman. Hilariously, this maternal ambition escalates from sewing him a cheesy costume and urging him to build up his muscles, as far as trying to endow him with powers by replicating other heroes’ origins, from a cocktail of herbs and minerals to a bite from a test-lab pooch, all to no avail. His mum even gives him a lift to his first disastrous attempt to fight crime.

Together with these more comedic touches, Yang and Liew ground their brisk, breezy yarn in the period and locale, rife with racism, organised crime, protection rackets and Chinese gang warfare. Along the way, they also neatly rationalise that turtle-shaped shadow which accompanies him, his knack for never getting shot, even his strangely pink skin tone. Their ‘ret-con’ rewriting of comic book history delivers enormous fun with surprising heart and relevance. As the recent controversy over the non-Asian casting of the American live-action re-make of Katushiro Otomo’s manga and anime classic Akira shows, these representation issues have never gone away. So The Shadow Hero is a timely reclaiming and restoration of a short-lived B-hero from the past who is finally given his overdue pride of place.

And here are the rest of my Top Ten superhero(-related) comics:

2: The Wrenchies by Fared Dalrymple (FirstSecond)

3: The Multiversity: Pax Americana #1 by Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely (DC - cover date January 2015)

4: Captain Rugged by Keziah Joens & Native Maqari (Damiani - strictly late 2013)

5: Copra: Round One by Michael Fife (Bergen Street Press)

6: Nemo: The Roses Of Berlin by Alan Moore & Kevin O’Neill (Top Shelf/Knockabout)

7: The Wicked & The Divine Vol.1: The Faust Act by Kieron Gillen & Jamie McElvie (Image)

8: Ms. Marvel Vol.1: No Normal by G. Willow Wilson & Adrian Alphona (Marvel)

9: Silver Surfer: New Dawn by Dan Slott & Mike Allred (Marvel)

10: City Strips #1-#4 by Point of Interest (PoI)

10: Surely among the oddest superhero-related comics of 2014 are the four (so far) City Strips comic books compiling nothing but panel after panel, one from each year of a specific series, of architectural scenes and features, emptied of all their heroes, cast, captions and balloons. In order they are: The Amazing City from Amazing Spider-Man 1-139 (1963-74); Supercity from Superman 1-200 (1939-67); The Incredible City from The Incredible Hulk 1-202 (1962-76); and Gotham from Batman 1-100 (1940-56). The result is like a more extreme version of the webcomic Garfield Without Garfield, which reimagined the strip by erasing Jim Davis’s irritating (to some) feline lead.

Stripped of their four colours and cleverly re-composed into new black-and-white page layouts, these panels still hint at their missing hero and his stories. It’s as if all of the action has taken place mere moments before, or is yet to transpire moment later. Or perhaps it is all going on unseen in the gutters between the panels? The series also seems to be asking whether a city still be alive when nobody is living in it and all human action vanishes? Dinners are uneaten, televisions unwatched, driverless cars roar down the streets, as we wander urban wastelands and barren interiors. Even so, these experiments become a peculiar distillation of the stark backgrounds, settings and decors which are unmistakable and essential to their respective icon’s narratives. Sprinkled are one or two tell-tale objects like baby Kal-El’s rocket or the tombstone of Bruce Wayne’s parents. If in doubt, the logo for each issue reminds you of their original source.

Slightly insane and unnerving, this is but one output from London-based Point of Interest formed in 2011 by Mike, Stuart Bannocks, Rosario Hurtado and Roberto Feo as “an open and independent research platform generating practice-based design theory.” What might be next? I for one would enjoy seeing their take on Fantastic City from Lee & Kirby’s Fantastic Four, or howabout Central City, either the noirish one from Eisner’s classic The Spirit or the streamlined Sixties’ one from the Silver Age, Infantino-drawn Flash?

MY TOP TEN MANGA OF 2014

1: Opus is a mind-blowing meta-manga by award-winning animation director Satoshi Kon. Kon died too young and long before his time, and sadly he left this serial unfinished, while he channelled his genius into movie-making. Nevertheless, it’s a thrilling concept as a struggling manga author or ‘mangaka’ crosses over from the 3D reality of his studio into the 2D realm of his comic pages, where he has to contend with the characters whose strings he pulls as the master puppeteer as they question and challenge his control. Kon comes up with some dazzling and sometime wacky interpretations of living inside the manga you have created, such as showing sketchy, incomplete characters, his assistant’s backgrounds roughly drawn or the cityscapes like flat scenery on a theatre stage (above).

The portal between our world and the word of the comic works in both directions, allowing his heroine to emerge from her paper dimension into ours ( a spread from the original Japanese version is shown above). The Dark Horse edition puts both of the original volumes into one, including a last, tantalising, unpublished chapter in layout form. Overflowing with ideas and imagination, Opus would have made an astonishing anime and certainly connects to the themes and dreams in Kon’s films. Discover this treasure and look out next year because Dark Horse are finally releasing Seraphim, Kon’s manga collaboration with his peer Mamoru Oshii.

2: Unlike the more widely translated shonen ai (‘boys’ love’) and yaoi genres of manga, homoerotic romances mostly created by women and for women, the more underground niche field of gay manga by and for gay men has been mostly overlooked in print form in English. That changed dramatically last year, when PictureBox led the way by commissioning Chip Kidd to compile The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame, translating nine of this author’s strongest short stories alongside a tenth, newly commissioned by Kidd himself. Hot on their heels, German publishers Bruno Gmünder began a series of longer Tagame manga editions with Endless Game, Gunji and Fisherman’s Lodge.

Now the editorial trio of Anne Ishii, Chip Kidd & Graham Kolbeins are back and have compiled Massive: Gay Japanese Manga and the Men Who Make It. This landmark 280-page Fantagraphics compendium presents Tagame first up, as a way to introduce eight other leading contemporary gay mangaka - Jiraiya, Inu Yoshi, Seizoh Ebisubashi, Kazuhide Ichikawa (see sample page below), Gai Mizuki, Takeshi Matsu, Kumada Poohsuke and Fumi Miyabi, not officially available in English before, except via online fan scanlations.

The emphasis here, as the title suggests, is on larger-bodied, heftier ‘beefcake’, more muscular and hairy - Jiraiya’s cavemen look more like prehistoric sumo wrestlers (above). These are in marked contrast to the generally boyish, hairless, slender types preferred apparently by women in their yaoi fantasies. While varied and divergent, all the artists spotlighted in this collection are, perhaps unsurprisingly, men. What’s particularly intriguing is that some women artists who want to draw more masculinised men than are typically acceptable in the shonen ai/yaoi fields, have joined gay male creators in the new magazine Kinniku-Otoko (‘Muscle-Man), founded in 2001. Here’s hoping for a future Fantagraphics volume bringing these mangaka and their fantasies into English.

In the meantime, Massive lives up to its title. Each artist gets a three-to-five-page profile, including cover and illustration samples, before a portfolio of their comics, some taken from gay magazines, others from small-press zines or ‘doujinshi’, others in the yonkoma or vertical, four-panel comic-strip format or made online as webcomics. The book includes photos of all the artists, a fascinating contextual intro and a parallel timeline of the history of gay culture and gay comics in Japan. A recurring concern is the threat to the livelihoods of these artists from fans’ and opportunists’ internet piracy. This volume may inspire some pirates to reconsider their actions and instead make contact with their favourite artists and work with them rather than against them.

Showcasing these taboo-breaking, uncensored, unashamed, multi-sensory manga (one creator drops in the memorable smell of ‘drying squid’), Massive stands out and proud as a vital addition to the bigger picture of comics and of gay cultures and tastes in Japan, and to the appreciation of the flowering of these modern masters of homoerotica.

3: In Showa: A History of Japan by Shigeru Mizuki (Drawn & Quarterly), Shigeru Mizuki interweaves the big sweep of national and international history with the smaller, everyday events of his and his family’s personal history, with commentaries from his yokai or ghostly host Nezumi Otoko or ‘Rat Man’, to make a chronicle of the whole of Japan’s tumultuous Showa era. Highly detailed, photo-referenced recreations sit alongside simplified caricatures of Mizuki, his father and other figures. These eight award-winning volumes are being issued two at a time by Drawn & Quarterly in a series of four extra-chunky 500-plus page bricks, covering 1926-39, 1939-44, 1944-53 and 1953-89. What better way to tell an epic modern history lesson than in these multi-layered, accessible manga?

And here’s the rest of my Top Ten Manga in English:

4: Sunny by Taiyo Matsumoto (Viz)

5: Prophecy by Tetsuya Tsutsui (Vertical)

6: The Man Next Door by Masahiko Matsumoto (Breakdown Press)

7: Flowering Harbour by Seiichi Hayashi (Breakdown Press)

8: In Clothes Called Fat by Moyoco Anno (Vertical)

9: Whispered Words by Takashi Ikeda (One Peace Books)

10A: Nijigahara Holograph by Inio Asano (Fantagraphics)

(Plus late addition, just discovered - 10B: Nothing Whatsoever All Out in the Open by Akino Kondoh (Retrofit/Big Planet)

MY TOP TEN BOOKS ABOUT COMICS

1: To know where we are going, we need to know where’s we’ve come from and 2014 marked the 250th anniversary of Hogarth’s death. In Thierry Smolderen’s revelatory study, first published in French as Naissances de la Bande Dessinée (‘Births of the Comics’), and translated in 2014 by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen for University Press of Mississippi, the Belgian theorist charts a succession of “births” from Outcault’s Yellow Kid back to Genevan pioneer Rodolphe Töpffer, but he toasts William Hogarth as the form’s prime 18th century precursor. Smolderen singles out the way William Hogarth brought together high and low imagery, from compositions based on the elevated rhetoric of history painting to the populist taste for symbolic emblems, graphic satires, signs and graffiti, fashioning a “polygraphic” language which is able to work with irony and humour on many levels and “pay witness to the complexity, tensions and contradictions of the times.” (The video above in French shows Smolderen commentating on Hogarth).

In his apparently sober moralising Progresses, Hogarth is himself looking over his shoulder and sharing an in-joke by ironically recasting the popular genre of edifying stories in pictures from late 17th century Venice, placing them in the grubby hurly-burly of London and treating them as worthy of being painted and then engraved with the sort of care reserved only for the most noble of subjects. Hogarth’s polygraphic language and playful subversion of traditions of illustration and art can still be found in the work of many subsequent cartoonists and of today’s graphic novelists.

Even if you already have the French version, you really must get this English edition as Smolderen has added an important all-new chapter re-examining the overlooked comics which he helped to reappraise in such Victorian weeklies as The Illustrated London News and The Graphic (see example above). As co-curator of The British Library’s Comics Unmasked exhibition this year, I was very pleased to include several of these significant comics from their bound volumes in the show. You can see further examples in Smolderen’s French online essays here. The Origins of Comics is essential, insightful reading for anybody curious about the multiple origins and developments of the comics medium, and I suspect will go on being revised as yet more (re-)discoveries are made which rewrite history.

2: It’s a brave soul who hopes to encompass the entire history of the world’s comics within one manageable tome. In Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present (Thames & Hudson), American connoisseurs Dan Mazur and Alexander Danner sensibly make this impossible task a little more achievable by starting their 320-page volume in 1968, setting the scene with a ten-page intro. That year makes sense in so many ways, as major changes and developments occurred in 1968, both in comics and in society, that paved the way for the revolutions to follow. More problematic though is their claim to offer ‘A Global History’.

Their preface admits that newspaper strips are mostly omitted and that their focus is mainly America, Japan and Western Europe, leaving vast swathes of the world largely or entirely uncovered. So, for instance, ‘A Brief History of Korean Manhwa’ is a late addendum to their penultimate chapter, all in nine paragraphs and no illustrations. The cover and interior design and type are rather obvious, using those Roy Lichtenstein dots and wearisome Comics Sans font and sticking to a formulaic grid and limited range of picture sizes. There is a great deal to commend, even so, as Mazur and Danner offer one of the few English-language books to offer such a range of coverage and examples. The history is here, the facts, magazines, characters and creators are here, but it is sometimes hard to serve up so much information digestibly and entertainingly and there is rarely enough space and wordcount for them to go much deeper and and especially to connect beyond a somewhat inward-looking, comics-centric perspective.

From a personal bias, I am of course pleased that British comics get a reasonable slice - two paragraphs on the underground era with a Hunt Emerson Street Comix cover, five and a half pages to cover from Dan Dare in 1950 to Zenith in 1986, and a flattering paragraph on Escape, which I co-edited and co-published, with Chris Long’s cover to issue 3 alongside sample pages from Eddie Campbell’s Alec and Savage Pencil’s Red Hot Jazz. Later, Tom Gauld gets a paragraph and page illo as well. Japan gets five whole chapters and these are very well done, certainly suggesting that manga have been ahead of the game since their early days - which may explain why the rest of the world is still far behind and trying to catch up.

The challenge in compiling this kind of history is to avoid what I call ‘listitis’, the disease of long lists of names, characters or magazines, giving profuse examples where perhaps fewer choices could have allowed room for more insight. Mazur and Danner largely avoid this and by packing plenty of additional detail in their ‘maxi-captions’ accompanying each image, they achieve a huge amount for such a generalist, mass-market title, selecting plenty of remarkable but often unremarked (in English) international creators and creations deserving wider exposure. Theirs does not come close to being ‘A Global History’, but most of what history they do cover, they do remarkably well. Perhaps they can be given a second companion volume to chronicle the rest of this story.

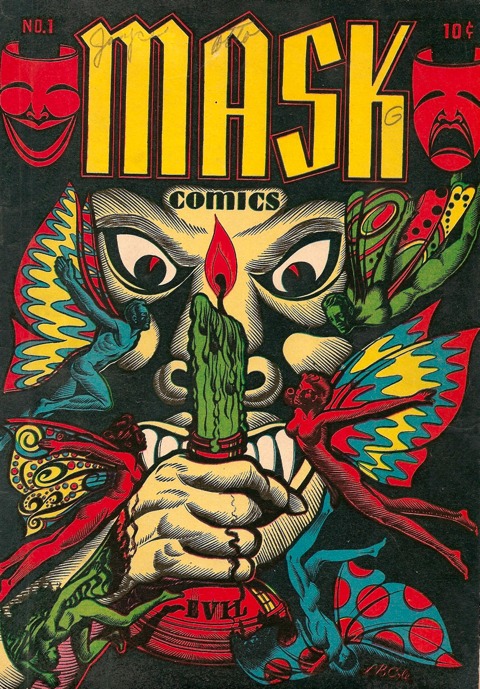

3: While the British wait for a deluxe artbook and biography on such late, great sequential art geniuses as Frank Bellamy, Leo Baxendale, Ken Reid, Ron Turner, Evelyn Flinders or Ron Embleton, to name but six, the Americans crack on with releasing sumptuous volume after volume on their outstanding creators from the past. 2014 has brought some true gems like Black Light: The World of L.B. Cole (Fantagraphics). Here’s you chance to luxuriate in the predominantly Fifties, ‘proto-psychedlic’, poster-like front covers by Cole, ravishingly choreographed by designer Jacob Covey and organised alphabetically from the brief Fifties fad for 3D titles and 4Most Comics to genre mash-up Weird Jungle Tales and Lone Ranger imitation, White Rider and Super Horse.

Covey shrewdly has these eye-popping feats of illustration, design and hand-lettering sharply reproduced onto black page backgrounds. The covers themselves are dominated by their forceful primaries of black, red, yellow and blue and make the most of the limited range of combination tints available with early four-colour hand separations, as well as by their own striking backgrounds, notably of solid red, white and Cole’s favourite, black. His view was, “The value of black in what the viewer will read into that black space. …[They] will read the most horrible aberrations into it.”

This oversize 272-page monograph really does justice to these covers, plenty shown considerably larger than their original size. Several are scanned from rare proofs, the publisher’s small number of first test-printings, of a high standard and often not necessarily printed on the same presses as the subsequent much larger main print run. Historian Bill Schelly’s biographical introduction offers facts and insights about Cole’s lengthy, varied publishing career, his shrewd, confident character, and his rediscovery in later life by fans and collectors. As Cole was inclined sometimes to exaggerate his past, Schelly corrects Cole’s claim that he produced 1,500 comic book covers down to the actual figure of around 350, of which a large majority are compiled in these pages, as four to a page, whole pages and bleed blow-ups. Among them are a few unpublished proofs, such as Gasoline Alley #3 and Shocking Detective Comics #201 (there were not two hundred issues prior to this one), and pencils for the curiosity cover of The Fox #13, presumed unpublished.

Special emphasis is placed on Cole’s inclusion of animals in hiscompositions, a real gift that can be traced back to his love of animals from time he spent living in Lexington, Kentucky after his parents’ separation, when he was 14, and his pursuit at one stage of qualifications to become a vet. Cole deserves wider acclaim for his inventiveness to maximise impact. He will collage elements at different scales into impossible scenes to fill the cover to bursting, integrating his bold, clear logos, typography and graphic design. Cole clearly made use of models or photo reference, notably on his more realistic romance comics covers.

Sad to say, hardly any of Cole’s actual black-and-white ink drawings for his covers, all drawn with a Winsor & Newton #3 brush at 37 cents each, have survived. Only one original for Target Comics Vol. 9 #4 is shown here. But more of his fully painted covers for Gilberton’s updates of their Classics Illustrated line and his gem for Dell’s Tales from the Tomb are presented, as well as a closing section on his later art and his work beyond comics, for men’s adventure magazines or for World Rod & Gun. The blunt truth is that what lay behind these riveting front cover images rarely lived up to what they promised. The cover was the thing that caught your eye, got you to pick it up and feel compelled to buy it. Cole himself drew only a modest number of interior comics pages, most when he began in the industry. His genius was making his totally unputdownable covers such alluring, attractive sirens, standing out on any newsstand, hypnotising us to pick them up and buy them, for the cover alone. No wonder so many have become iconic, even eye-conic, classics.

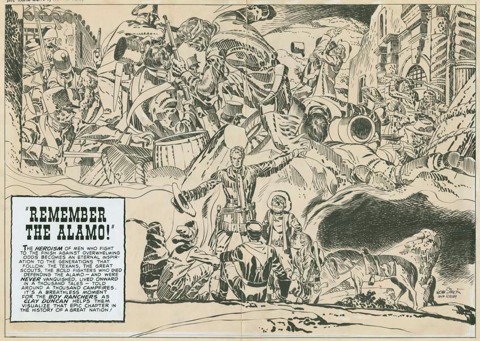

4: Some book projects can take their time to come to fruition. The concept of The Art of The Simon and Kirby Studio (Abrams ComicArts) goes back to correspondence in 2008 and a contract in 2009 between Joe Simon and Abrams. At that stage, it was unusual to imagine a book reproducing the original artwork from comic books in all their slightly faded, pencil and ink splendour. This was way before the recent boom in Artists’ Editions led by IDW, publishing comic book art in its original scale in deluxe oversized hardcovers.

Former Kirby assistant and Kirby’s biographer Mark Evanier has edited, annotated and introduced this compendium of over 350 pages of artwork produced by the Simon and Kirby Studio and mostly sourced from the late Joe Simon’s personal archive. To be accurate, this is not titled The Art of Simon And Kirby so it is not all by the great duo, as around 90 of these pages are illustrated by other studio members. The great Mort Meskin and Doug Wildey are among them, and two revelations for me were seeing Bill Draut’s fine chiaroscuro draughtsmanship, developing from his early clear Milton Caniff influence, and discovering the name of the Argentinian artist Joaquin Albistur, whose masterly brush style I had admired without knowing his name or origins.

Interesting and well-crafted though these pages by other hands mostly are, I can’t help preferring to have seen more pages by Joe and Jack. Corporate copyrights sadly rule out any art from National/DC or Timely/Marvel. Nevertheless, out of all the bountiful, beautiful pages of Simon & Kirby artwork for their chilling horror anthology Black Magic or their revolutionary love comic Young Romance, each series is represented by only a single splash page. Those romance covers shown here are mostly later, tamer, post-Code approved series like Young Brides or In Love. In the end, the book has to be based around what is in Joe’s own collection.

Still, there is loads and loads to appreciate here, the largest S&K chunk being seventy pages from Boys’ Ranch (Alamo spread above), including Kirby’s all-time favourite story ‘Mother Delilah’ in full. There’s also around 60 pages of their entertaining post-Code fantasy and sci-fi material for Harvey, some inked by Al Williamson, and a healthy sampling from their late partnership for Archie Comics on The Fly and Private Strong. Unpublished pieces include extracts from Boy Explorers and Stuntman and, new to me, an abandoned superhero concept cover from circa 1955 introducing Sunfire, Man of Flame. Fittingly, Evanier’s final choice is the unused Kirby cover, inked by Simon, for The Sandman No. 1, the 1974 one-shot revival that reunited the team for one last, successful collaboration.

The real pleasure of this tome is the direct contact we finally get with so many of these physical artworks created collaboratively in the Studio and sent off for reproduction. It’s a rare chance to get up close and personal and intimately observe all the types of mark-making on these pages. These visuals and stories take form from vigorous pencilled foundations onto which are added the skilful layering and interplay of linework and solid areas of ink, their weights ranging from the driest of brushstrokes to the firmest blocks of black, the whispiest feathering to the deepest shadows for heft or mood. Did Joe, Jack and company know how much of their labours would be lost, when put through the crude colouring and printing processes on absorbent newsprint paper stock? If they did, it didn’t stop them putting consummate skill and passion into every panel.

These boards may have browned now, revealing touches of White Out corrections, sepia stains of glue where captions or balloons have fallen away, edges and corners crumbling, but they have survived. They are rare, hand-made, pre-computer works on paper which still compellingly communicate the aura of their storytelling and artistry. On this tome’s cover sits the heroic artist focussed at his drawing board, shirt-sleeves rolled up, robust right hand delicately grasping his pencil. Seeing comics art in the raw and en masse like this really brings it to life and conjures up the people who made it. So much so, you can sense the hands, brains and hearts behind every line, and almost smell Jack’s infamous cigars.

5: America has only one peer-reviewed academic journal specialising in comics, ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, published by the Department of English at the University of Florida (and I can thoroughly recommend John Lent’s non-peer-reviewed International Journal of Comic Art), whereas Britain boasts no less than three - Studies in Comics (Intellect), The Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics (Routledge) and European Comic Art (Berghahn). For its Spring 2014 edition, forty years since its founding in 1974, the University of Chicago’s journal Critical Enquiry has devoted for the first time a whole issue to ‘Comics & Media’. Guest editors Hillary Chute and Patrick Jagoda, who teach at the University, interweave the proceedings of the May 2012 conference ‘Comics: Philosophy and Practice’, organised by Chute and held under the university’s auspices, with papers on media including comics, both old as in print and new as in digital.

Breaking with tradition, this issue comes in an expanded format close to the size of an American comic book or graphic novel to accommodate a wealth of visual content including new comics and illustrations, and two elaborate foldouts. One of these is the conference poster in strip form by Chris Ware, in which he jokingly refers to comics as “a.k.a. Graphic Novels, Metastatic Pictofiction and Dime Store Funnybooks” (detail below).

The extraordinary conference and the book that transcribes its solo interviews and panel discussions comes across as a sort of dysfunctional family reunion or gnarled, twisted family tree. All of the cartoonists here are connected to and inspired by Crumb, from his wife, collaborator and pioneering autobiographical cartoonist Aline Kominsky and other underground contemporaries like Justin Green or Art Spiegelman from Crumb’s generation, to their successors like Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel, Charles Burns, Chris Ware, Joe Sacco, or Daniel Clowes. So the result is resolutely biased away from the corporate-owned, superhero-dominated, mass-market output of Marvel and DC and towards the literary and artistic cutting edges of the medium in the USA, with Seth as the sole non-American, Canadian participant. This enforced binary gives proceedings a focus but may isolate these creators from their dialogue with and place within wider comics culture.

Putting practitioners and academic together can be a productive though occasionally bumpy ride. Not all comics creators relish close analysis and ‘critical inquiry’ of their output, and there is noticeable tension on one panel between Françoise Mouly, art editor for The New Yorker, and Crumb whose rejected 2009 front cover has finally been used at this volume’s cover. But there is much to be learnt and thought about here. And whenever the debate threatens to get too high-flown, Crumb will bring proceedings back to earth by interjecting something amusing. As he reminded Chute in a postcard accepting his invitation to the conference: “Let us keep in mind, this is about comic books!”

6: Acclaimed anime and manga expert Helen McCarthy is our guide through A Brief History of Manga (Ilex Press), ‘Brief’ meaning a 96-page miniature hardback in a format similar to those fondly remembered Ladybird books. This is an exemplary achievement in distillation of a truly vast comics culture, organised chronologically from manga’s pre-history circa 700 CE to 2013’s era of Kickstarter and rapid intercontinental cultural cross-pollination. Each of the 44 spreads offers a main text and side box on the left, opposite a right-hand page of illustrations, mostly front covers. Cleverly along the bottom of the left-hand pages runs a timeline of important dates and facts in circles, colour-coded for people’s births and deaths, magazine launches and cancellations, historic events, etc.

As an English-language book, quite a bit of emphasis is placed on translations, influences in American comics, and on the more recent international crossover of manga over the last thirty years or so. A Japanese version of this book would of course be quite different. From 1982 and the debut of Akira, the coverage becomes more in-depth, almost year-by-year, with only a few gaps along the way. No other book has summarised the complex chronicle of Japanese comics from their roots and growth to their latest forms so succinctly, enjoyably and affordably. It would be hard to find a finer primer.

And here are the rest of my Top Ten Books About Comics:

7: The Art Of Neil Gaiman by Hayley Campbell (Ilex Press)

8: Death, Disability, And The Superhero: The Silver Age And Beyond by José Alaniz (University Press of Mississippi)

9: Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed The World by Monte Beauchamp & various artists (Simon & Schuster)

10: Southeast Asian Cartoon Art: History, Trends and Problems by John Lent & others (McFarland)