Nell Brinkley:

A New Woman In The Early 20th Century

In any walk of life, one sign of making it is to become part of the language itself. Such was the popularity of the stately, coiffured beauties illustrated by Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944) that his ‘Gibson girls’ went into the American dictionary. Sadly, his successor, Nell Brinkley (1886-1944), has not enjoyed such lasting fame, although in her time she had an enormous influence on the appearance and aspirations of women across America and beyond. A high-school dropout and self-taught illustrator from the tiny frontier town of Edgewater, Colorado, population 311, Nell was just 21, when she broke into the New York newspaper world in 1908 with her vivacious, curly-locked beauties. Within only a few years, her new ideal of fun-loving feminity swept away the stuffy ‘Gibson girls’.

All that Gibson’s passive high-society mannequins would do on the beach is pose elegantly with a wistful, rather corseted gaze. In contrast, ‘Brinkley girls’ bounded onto surfboards, kinky hair flying, dress straps loose off their shoulders, smiling with glee. They became a national craze, serenaded in pop songs and in the Ziegfeld Follies, syndicated in Hearst’s newspapers and to The Sketch in Britain, merchandised as cosmetics and curlers, and modelled by young women coast-to-coast. And yet, the ‘Gibson girl’ is still well-known today, whereas the ‘Brinkley girl’ is all but forgotten, probably because she was too independent and disturbing a sex symbol for the stay-at-home Fifties.

Miraculously, thanks to the Goddess of the Internet, a two-foot-high archive of Brinkley clippings was entrusted in 1997 to comic artist and historian Trina Robbins, who has crafted a long overdue biography, Nell Brinkley & The New Woman In The Early 20th Century. Additionally, a short appreciation by Trina and 38 pages of Nell Brinkley’s comics can be found in The Comics Journal #270, August 2005.

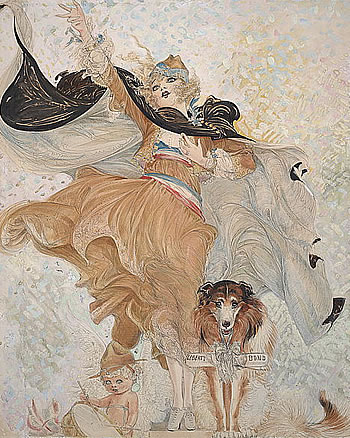

Like others, Trina had admired Nell’s elaborate draughtswomanship and romantic sentimentalism, but now, thanks to this resource, she was the first to re-read closely the texts Nell wrote for her cartoons and discovered that, amongst the hearts and flowers, in much of them "she was a chronicler, a feminist, a blood-and-thunder storyteller". Nell commended the new working women - she was one herself, only able to slave daily over her drawing board, because her mother was her manager and housekeeper. She celebrated women’s achievements, profiling First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and solo pilot Amelia Earhart (Nell flew in a biplane herself). In her finest hour, in a patriotic fifteen-week colour cliffhanger, her First World War heroine Golden-Eyes and her Lassie-like pooch Uncle Sam go overseas and brave No-Man’s Land to rescue Bill, her heart-throb hero.

Across her seven chapters, Trina chronicles Nell’s life and career, focusing in her opening chapter on 1908, the key year when the Brinkley Girl phenomenon rapidly captivated the American imagination. Almost from the start, Nell’s fellow New York Evening Journal cartoonist ‘Tad’, alias Thomas Aloysius Dorgan, would wickedly parody her very feminine cartoons the following day on the male-dominated sports pages, and Trina juxtaposes several of these good-natured duels. She also explains how Nell’s initial fame was boosted by her courtroom drawings reporting on the ‘Trial of the Century’ of Harry K. Thaw, her illustrated theatre reviews and profiles of society ladies. Elegance is everything in Brinkley’s drawings, right down to her elongated and curled signature decorating across their foot.

In her survey ‘Before Nell’, Trina provides the history and context of Nell’s changing times, as more opportunities gradually became available to American women in the new century and as illustration became an acceptable occupation for a number of successful women artists. Trina’s choice quotations from Nell’s cartoons and their accompanying breathless prose shed light on Nell’s growing awareness of women’s rights, commenting on the suffragette movement and the roles women were playing in the War. Throughout, Trina weaves evocative anecdotes of the period when cartoonists were celebrities mixing with movie stars and the president’s wife, and even co-starring with other Hearst cartoonists in a tantalizingly ‘lost’ 1924 film The Great White Way. Sadly, Trina found that Nell’s marriage did not end as romantically as in her fictions. Nell was shattered when she chanced on her idealized husband, twelve years her junior, in the theater with his mistress; divorcing him in 1936, she found some outlet for her disillusion through a series entitled ‘What Went Wrong With Love?’, but the bloom of romance had faded forever.

Nell had always refused to create comics, despite the urgings of Evening Journal editor Arthur Brisbane. Nevertheless, she would occasionally produce multi-panelled thematic pages and some narratives, that are essentially comics. One good example of these, ‘The Five Senses’, was selected by historian Thomas Craven to represent her in his mammoth 1943 anthology Cartoon Cavalcade. In his commentary, Craven regrets that, unlike in the prewar French magazines La Vie Parisienne and Sourire, "the charms of sex have never found their way into American cartooning". He then brings on Miss Brinkley: "The closest approach to the French acceptance of sex appeal appeared in the drawings which Nell Brinkley used to make for the New York Evening Journal. The drawings themselves were amateurish, but from the girls, the little brides and sweethearts dolled up in frilly transparent gowns, emanated a charm, an enticing jeu d’esprit which no other cartoonist has managed to capture."

Still, Craven’s praise is faint and superficial, snobbily poo-pooing her drawing talents. It has taken Trina, after all these years, to dig deeper beneath the surface glamour and examine both Brinkley’s pictures and her words. From them emerges the singular vision of a free-spirited woman, whose role in shaping 20th-century feminism and art history is now finally being recognised. Her true heiress, in Trina’s view, is Dale Messick in her Brenda Starr, Reporter strip, a convincing claim, but Trina is too modest to assert herself as another in Nell’s lineage, as an impassioned proponent of women cartoonists, a distinctive voice in comics herself, and almost modelling herself as a 21st century Brinkley girl with her bubbly curls and bubblier personality.

Trina acknowledges one disappointment with this biography, that the generous broadsheet scale and subtle, delicious colouring of so much of Brinkley’s artwork cannot be reproduced in this standard sized, black and white paperback. Based on the bedazzling examples Trina showed in her slide lecture which I attended in September 2001 at the Ohio State University Cartoon Festival in Columbus, I can’t wait to see a larger follow-up artbook to do them justice.

The original version of this article appeared in 2002 in the pages of The Comics Journal, the essential magazine of comics news, reviews and criticism.