Marcel Ruijters:

Hieronymus Bosch

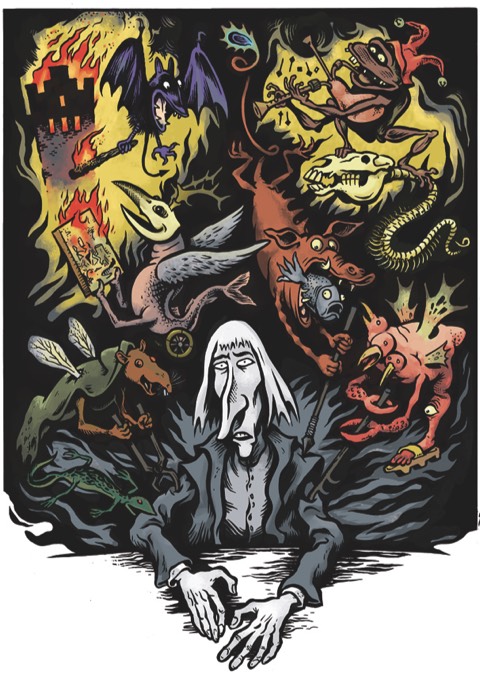

This year marks 500 years since the death of Jheronimus van Aken, world-renowned as the fifteenth-century Netherlandish painter of earthly and unearthly delights, Hieronymus Bosch. His quincentenary has been widely trumpeted by the Bosch500 Foundation in various projects including the largest ever exhibition at Het Noordbrabants Museum in ’s-Hertogenbosch, where he was born. Few are so strikingly original, however, as Hieronymus, a vibrant graphic biography commissioned by the Foundation from award-winning Dutch underground cartoonist Marcel Ruijters. He cleverly refers to several of Bosch’s works and creatures, but avoids any attempt to re-create actual paintings, instead illustrating with a vigorous woodcut style and aptly grotesque caricaturing.

Hieronymus is organised into six chapters by key turning points, from a flashback to the great fire of 1463 in Bosch’s birthplace to a visit from Death. As only a limited amount of information has survived about his life, Ruijters fills in some of the blanks by building on other sources, such as what is known about his contemporaries Matthias Grünevald and Martin Schongauer. To flesh out the life story further, Ruijters invents a miniaturist master painter, Brother Gerardus, with whom Bosch could plausibly have trained. Ruijters also scoured Bosch’s financial records to learn more about his character; after all, as the cartoonist comments, “the way a person spends his money says a lot about his character”.

Equally revealing for Ruijters’s research were the paintings’ close connections with the theatre and popular culture of the period, as analysed by Belgian scholar Eric De Bruyn. These layers of meaning make Bosch’s masterpieces, all of them commissioned, ripe for reinterpretation. Plenty of myths have arisen about them and their painter, which Ruijters takes great pleasure in debunking, such as the popular misconception that Bosch was some kind of heretic, which is ruled out by the fact that the church at that time was not opposed to alchemy. As for where those unforgettable demons sprang from, Ruijters demonstrates how Bosch did not use drugs but used his ears to closely connect his work to oral history and wordplay. He also used his eyes to look around him and record the disturbing and brutal in everyday life; as Ruitjers has Bosch remark, “I paint what I see here, as if Earth is the Hell of some better world.”

Ruijters is an inspired choice for this task. In 2015 he was awarded the Stripschapsprijs, the most prestigious Dutch prize for comics, for his entire oeuvre. His career began in the late 1980s when he emerged first in self-published comic books, before contributing to alternative anthologies such as the Rotterdam-based Zone 5300, which he went on to edit. The art of the Middle Ages had a profound effect, transforming his work from the late 1990s. “Besides its obvious otherworldliness, I found medieval art to be quite like comics. There’s often a narrative, the art is symbolic, linear and usually crammed into tiny boxes.” Ruijters’ Sine Qua Non (2005) plunges the reader into a feverish fable between nuns and demons, devoid of dialogue but laden with mystical symbolism. In 2008 he adapted Dante’s Inferno, taking inspiration from Giovanni di Paolo and Bartolomeo di Fruosino among others, and in 2012 he compiled convincing, make-believe lives of women martyrs into All Saints.

Ruijters’ new Strip for ArtReview serves in part as an epilogue to the biography and is based on the writings of José de Sigüenza, a Spanish Hieronymite monk and historian. “In the mid-16th century Sigüenza defended Bosch against posthumous accusations of heresy circulating around the Spanish court.” The medieval world was changing. At one point in Hieronymus, Bosch’s tutor and fellow religious painter Gerardus speculates whether ‘…our fine profession will be destroyed, not so much by the printing presses, but by those who wish to worship an invisible god, as the Moors do?’ Here Ruijters is giving us a premonition of the Protestant revolution, which was to begin one year after Bosch’s death. “I am not hinting at the rise of Islamism here, but the digital revolution, which in my view poses a much bigger threat.”

New Bosch Strp for ArtReview Magazine

Click images to enlarge.

Web Exclusive:

Presenting here the complete email interview I conducted by Marcel Ruijters - many thanks for all these responses.

Paul Gravett:

What impact has Bosch’s work had on your own art and life?

Marcel Ruijters:

A deeper understanding of how your art should be full of meaning. Materials were scarce at the time, so nothing was wasted. One would not draw stuff just for fun. As I grow older, that message hits home.

What were the biggest challenges in researching and creating a graphic biography of Bosch?

Basically that the information about his person is quite limited. Too much has been lost - if it had been recorded at all. As a result, a lot of nonsense has been written about Bosch, so it takes some time before you know how to weed out the bad books. And one has to learn a lot about the time in which he lived. For instance: yes, there are references to alchemy in his work, but the church was not against alchemy, so that rules out the popular misconception that he was some kind of heretic, which determines what kind of story you are going to write. On top of that, getting your historical facts straight is one thing, creating a meaningful story out of it, with believable characters, is something else!

How did you overcome the lack of full detail about Bosch’s life?

I had to fictionalise a lot (the storyline with the conflicts within Bosch’s family is entirely my invention), but I could fill in some blanks by borrowing from what is known of his contemporaries, like Matthias Gruenewald or Martin Schoengauer. Also, some paperwork has been preserved: loans, sales of property and such. My accountant taught me that the way a person spends his money says a lot about his character. And I have drawn a lot from the work by Eric De Bruyn, a Belgian writer who has done an excellent thesis, in which the connection with theatre and popular culture of that time is explained in great detail. So I had more material than just the paintings to interpret.

The 500th anniversary of Bosch’s death in 2016 is bringing many commemorations. What is the most important relevance of Bosch today, what is his legacy?

That depends on who you ask. What proved to be crucial for my book is finding a comparison to Elias Canetti, observer of irate crowds. If Bosch paints for instance a calvary, I feel that it is more of a comment on the folly of man than it is about Christ. Folly was almost synonymous with evil in his day. To paraphrase Tolstoy, there is one way to be good, and many to be evil/sinful. Of course Bosch followed the morality of his commissioners, and moralists are more interested in ugliness than in beauty, but as an artist it is also natural to be interested in the variety that evil has to offer.

What do you feel remains the most misunderstood aspect of Bosch’s life and work?

It is not widely known that his inventive demons are based on wordplay. This makes him more of an illustrator than the official art world would like to admit, because it holds illustrators in low esteem. It may sound a bit pedantic, but I think you must have a deep understanding of medieval Dutch to see how closely connected Bosch’s work is to oral history. In short, he did not use drugs to come up with those crazy visions, but his ears. Of course, I have taken great pleasure in debunking these myths.

You emerged as a comics artists from the Dutch underground scene and in the Rotterdam-based anthology Zone 5300 - who were some of your formative influences during this stage, from comics and elsewhere?

That would be a long list, with names from all over. I continue to enjoy the bold, whimsical graphics of Matti Hagelberg, for instance. The brushwork of Roy Tompkins is still important to me. The work by the Neue Slowenische Kunst movement taught me a lot.

What was it about the Middle Ages and perhaps their art, illuminated manuscripts and illustrations of alchemy which first sparked your interest and changed your comics so much from the late Nineties?

Beside the obvious otherworldliness, I found medieval art to be quite comic-like: there’s often a narrative, the art is symbolic, linear and usually crammed into tiny boxes. Despite the wave of historical comics in France since the 1980s, no-one had adopted the stylistics in a consistent way, so I stumbled upon virgin territory, as far as I know.

In what ways did other artists, apart from Bosch, inspire your medieval-themed books to date, such as you adaptation of Dante’s Inferno, your graphic novels Sine Qua Non and All Saints, or your art book 1348 from Le Dernier Cri (image, above)?

That would also be a long list, and unfortunately, many artists are anonymous. But Giovanni di Paolo and Bartolomeo di Fruosino were important to my adaptation of Dante’s Inferno.

Is all your black and white linework done in pen and ink? What techniques and media do you use? Do you use computers only for colouring and lettering?

I draw with brushes and fine markers on glossy paper, which allows you to gently erase the ink to create fine white lines. Colours are indeed done digitally. I would not like to go fully digital.

You have also illustrated your own interpretation of The Tarot, originally silkscreened by Le Dernier Cri in 2004, which swiftly sold out. In 2015 you revised and expanded this into a full 80-card limited-edition set from Sherpa (see here for details and preview and read Ruijter’s introduction below). What are the connections in The Tarot’s visual language to Bosch’s work?

That remains rather vague, but the imagery of the Tarot and Bosch’s work share common origins. His Wayfarer has been taken from the model of the Fool (note the shabby clothing and the dog biting at his legs) and his Conjurer behind his table with objects looks quite like the Magician.

Could you discuss the interesting comment by Brother Gerardus on page 129: “…our fine profession will be destroyed, not so much by the printing presses, but by those who wish to worship an invisible god, as the Moors do”? Do I detect an echo of the Charlie Hebdo massacre here?

This is meant to be a premonition of the Protestant revolution, which started just one year after Bosch died. Protestant hardliners had a similar problem with “idolatry” as the current extremist offshoots of Islam (and making life rather difficult for artists). Protestantism had been “in the air” for decades during Bosch’s lifetime. I am not hinting at Islamism here, but the digital revolution, in my view a much bigger threat.

What is the historical background to the new strip you’ve created for ArtReview?

It is based on the written words of José de Sigüenza, who defended Bosch against the accusations of heresy that were floating around the Spanish court in the mid-16th Century.

What in particular makes the Middle Ages so very different from our present day? And what similarities do you also see - have the fears and follies of humanity changed very much since?

I think we have to look at the troubled parts of Africa today to understand some of the anxieties of medieval Europe: famines, epidemics, civil wars that can strike at any time… No wonder people were desperately religious. But at the same time, medieval society was rife with distrust. The guilds were suspicious of each other, burgers distrusted peasants, and so on. City life was just starting up again in the late Middle Ages and most must have felt displaced and uncertain of their position.

Web Extra: Marcel Ruijter’s Introduction to The Tarot published by Sherpa, Netherlands, 2015:

“To foster a certain fascination for the Tarot is not exactly unique…

“Since my earliest youth, I have been drawing monsters, freakshows and the like. In short, physical oddities. Skeletons are intriguing for child. You know it is must be inside of you, but it stays unseen and so you are likely to develop a curiosity for anything that grown-ups will try to keep out of sight from you. In any case, the skeletons of my childhood drawings have stayed. Horror films and books about the freakshows of olden times have been a rich source of inspiration over the years, but gradually physical outlandishness had to make room for bizarre ideas. By the end of the nineties, medieval art and illustrations dealing with alchemy started to make their way into my world.

“Speculating about the oldest origins of the Tarot makes for a pleasant pastime. Some claim to see links with the I Ching, the Zodiac and Nordic Runes, which would point toward very ancient roots, but much of the visual language of the Tarot arguably derives from late Medieval popular culture. The paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, as strange as they may seem to the modern eye, are firmly rooted in a tradition that has some connections with this. For instance, his Wayfarer strongly resembles the first trump card, The Fool. Both characters are poorly dressed while a dog is trying to bite them. Also the second card from the Great Arcana, The Magician, we find among Bosch’s body of work, standing behind a table with mysterious objects on top.

“Artists’ appliances were scarce in the Middle Ages. An artist was forced to produce most of his materials himself, which explains why very little was wasted and every detail in Medieval art is loaded with substance. Much of the original contact, including the Tarot, however is lost on us. Everyday change or dramatic disaster? I’ll leave that to historians – there will be as many explanations as there are books to consult about the cards’ meanings. And that may be a good thing in itself. While looking into the matter, inspiration will fill the gaps in the artist’s knowledge (which includes comics creators, even some who will never regard themselves as artists). Knowledge will extinguish that little flame of curiosity, the journey being the goal, and all that. And I certainly don’t claim any deep knowledge of the Tarot…

“Nonetheless, I would like – maybe superfluously – to point out a widespread misconception, namely that the cards are not meant to predict the future, but to offer a way of meditation upon one’s present. In popular films, when cards such as Death or The Devil are drawn, it constitutes the promise of many exciting problems for the hero – much to the pleasure of the viewers. It’s a writer’s trick which in some way carries on the church’s doctrine. The philosophical system of the Tarot is said to have been obstructed by the church by taking two cards (Intuition and Truth) out of the Great Arcana, as it was perceived at the time as some kind of witchcraft. By adding these two back, their number is 24, which feels like a more “natural” number, by which associations with the Zodiac and so on seem more plausible. This is called the “restored order” of the Tarot.

“The popular culture of the late Middle Ages was rich with a sense of irony. Therefore, I don’t hesitate to use a humorous approach. It is not out of disrespect. Playfulness, an absence of dogma fits the realm of mysticism to which the Tarot belongs. Of course, there will be connoisseurs who strive for a certain “purity” and who will reject my liberal interpretation of the Tarot. I wish them good luck. The imperfections of medieval art have always struck me as disarming and charming. The many similarities with comics are obvious – which spurred me on to do a deck of my own design. For this, I took the 15th century Tarot of Marseille as a big source of inspiration.

“A first edition appeared in 2004, lovingly silk-screened by the good folks of Le Dernier Cri, situated in Marseille, France (of all places). Albeit confined to just the Great Arcana, it sold out quickly and people kept inquiring about it. A sense of success turned to frustration and so I decided to produce a complete, fully revised edition. My game with the symbolisms could use some elaboration. Some cards turned out surreal, others came out as surprisingly close to their original content… And in some cases, people will have to tell you the deeper meanings of what card you have drawn!”

Posted: August 27, 2016Edited versions of the opening Article appeared in ArtReview and the Times Literary Supplement.