Leo Baxendale:

A World of the Unforeseen

The undisputed, uninhibited guru of ‘The Beano Spirit’, Leo Baxendale was credited by UK comics historian Denis Gifford in The World Encyclopedia of Comics as “the most influential and most imitated comics artist of modern times”. Generation after generation of British children have grown up with his hilarious strips and dozens of cartoonists have imitated his styles as they changed over the years.

According to Alan Moore, growing up on Baxendale in The Beano explains why he and so many British comics creators since the 1980s have subverted and revitalised American comic books. “We started out ingesting the genuine anarchy of The Beano, when Baxendale was doing all that wonderful stuff, and then we moved on to American comics. We just became fascinated with all that gaudy exotica. But we approached those comics with a certain sensibility that home-grown US comic creators don’t have.”

_12th._March_1960SMall_.jpg)

It was sixty years ago, in 1953, that Leo Baxendale created Little Plum, Minnie the Minx and The Bash Street Kids while living in Preston. Letters were flying back and forth between D. C. Thomson, publishers of The Beano in Dundee, Scotland, and Baxendale, who sent them drawings of his creations from scripts, plots and storylines written by himself. By the time he moved to Dundee at the end of November 1953, Little Plum, Your Redskin Chum had burst out of the pages of The Beano starting on October 10th 1953. Barely two months later, on December 19th 1953, Baxendale introduced Minnie the Minx, and another two months or so after that, on February 13th 1954, The Bash Street Kids completed a hat-trick and triple whammy.

Since then, their creator has dreamed up many other popular characters in getting on for 6,000 pages of comics for D.C. Thomson, The Beano‘s publishers for 75 years plus in Dundee, Scotland, and later for WHAM!, SMASH!, Monster Fun and more from IPC/Odhams/Fleetway. Of these, over threequarters were both written and drawn by Baxendale. After 22 exhausting, high-pressure years in the children’s comics industry, he quit the two publishing giants forever in 1974 to work on three annual Willy the Kid books (the cover of the third, last and rarest, is below) and a revealing memoir of his career entitled A Very Funny Business published in 1978.

Starting in 1980, Baxendale’s next magnum opus was his landmark court case against D.C. Thomson, in which he sued them for the copyrights to his creations. Some thirty years ago, in 1984, he took time off from his paperwork for a plate of bangers and mash and a chat with me in the front room of his bungalow outside Stroud for the fifth issue of Escape Magazine. Born in 1930 in a Lancashire village, Leo struck me as solidly built and soft spoken and explained how had just finished helping Martin, his son, eldest of five children, a cartoonist and keen gardener like his father, to move his entire garden! In 1987, Baxendale’s seven-year lawsuit was finally settled. Shortly after, I interviewed him again in Escape. He spoke about this as well as the sad death of his friend brilliant Beano cohort Ken Reid who had died earlier that year, and about his brand-new album Thrrp! from Knockabout. He would go on to produce a weekly newspaper strip of Baby Basil for The Guardian, retiring from regular comics production after the final instalment on March 3rd 1992 to devote himself to his continuing publishing projects from Reaper Books.

Last summer, I heard from Baxendale about his plans for an exhibition to mark the 60th anniversary of his Beano creations, to be held in September and October 2013 at The Lansdown Gallery, Stroud. This would have coincided with his 83rd birthday. In his advance information, or ‘Other Words to dance attendance on an exhibition of drawings’, he wrote about one of the two Little Plum original half-pages in his possession from 1957: “With my creations for The Beano, I was intent on bringing into being a world of the Unforeseen. ... Disasters happened to my pen and ink offspring from two causes - either from sundry ‘sudden gusts’, or as unintended consequences of actions that had been set in train by the characters themselves.”

Unfortunately, this retrospective did not take place. Nevertheless, the year ended with the great news that he was the second inductee, after Raymond Briggs, to the British Comic Awards Hall of Fame, announced to rousing cheers at the Thought Bubble Festival in Leeds. Baxendale cannot travel very far these days, so he suggested that his friend, cartoonist Jacky Fleming, receive the award on his behalf. In her speech, she mentioned that Baxendale had received an invitation some years ago to Buckingham Palace for the Queen’s garden party, which he had firmly but courteously refused. (As a footnote, unknown to him, a campaign had been started later that year by admirers to nominate him for an MBE or Member of the British Empire award; had he known, Baxendale commented to his friend Bryan Talbot that he would have stopped them.) So it says a lot that Baxendale chose to gratefully accept the British Comic Award from his peers in the comics world. Clearly, Baxendale is a man of strong principle, as seen in his disinterest in the ‘honours’ system, as well as his single-handed, single-minded legal challenge to Thomson’s.

A fascinating, lesser-known side of his output and character is the Strategic Commentary, a two-page activist newsletter which, in his words, “...sought to demonstrate, on grounds of cold military logic, that America could not win the war in Vietnam, and should therefore withdraw.” Baxendale typed it up and arranged the printing himself and roped in his wife and four kids (the fifth and youngest was too young) to help with the envelope-stuffing and mailing out. On his Reaper Books website, he reprints some text extracts and mentions that his first paid subscriber was none other than Noam Chomsky. Baxendale somehow found time and energy to publish this political weekly between early 1965 and June 1967, at the same time as he was creating his weekly deluxe ‘Super-Beano’ WHAM! for Odhams (the payroll record on the colour Eagle-Eye, Junior Spy spread below confirms he was paid £80 for this, a substantial rate for this period).

As he recalls on his website: “When I created WHAM! comic for Odhams Press, I found myself, for a brief span, earning more than a cabinet minister, and I used the disposable income to finance the Strategic Commentary. My money was steadily drained away, though, by the cost of sending hundreds of free copies each week to Labour members of parliament. Vietnam was an American war; but we were English, and we had two aims: to demonstrate to American subscribers that America could not win, and should therefore withdraw; and to persuade the Labour government of Harold Wilson to withhold British support from the Vietnam adventure, and to rid Britain of the delusion of past grandeur, the ‘East of Suez’ syndrome. When we moved south in June 1967 we had to stop the Strategic Commentary: the sort of ultra-quick printing set-up that we found in Dundee did not exist in the Cotswolds; the double bind had finally drained my resources; and my brief spell of earning-more-than-a-cabinet-minister had been and gone.”

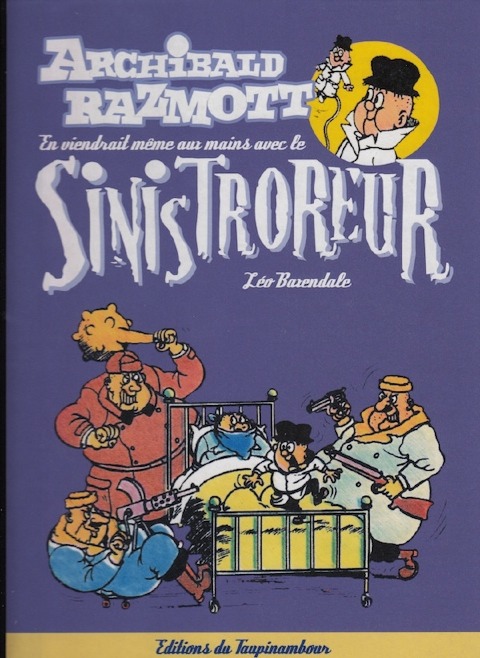

At the Angoulême International Comics Festival in January 2011, I was invited to give a 90-minute illustrated lecture in French about Baxendale. In my researches, I found that his influence extends well beyond British shores. Among others, his sublime Eagle-Eye, Junior Spy series in WHAM! was translated into French in the Disney magazine Journal de Mickey as Archibald Razmott. Mini-Barbouze de Choc, while his arch enemy Grimly Feendish was known as Sinistroteur. Episodes were later compiled into six very limited-edition hardback albums (the first is shown above) released from 2007 to 2010 by Éditions du Taupinambour, and 244 pages of it are scanned on Flickr here. Insanely, nobody has reprinted them in English, yet.

While I am uncertain about French versions of his D.C. Thomson’s characters, several more of his later creations did hop over the Channel starting around 1969-70, including “Bad Penny” (alias “Petsy la Peste”), “The Man from Bungle” (“Larry Tournel” in France reformatted for the digest-size colour quarterly Oooh!), “Percy’s Pets” (“Pimpin et son zoo” in the bi-monthly Akim also from Aventures et Voyages (Mon Journal), and “The Tiddlers” (re-named “La Bande à Zozo”). Ironically, many of these episodes and covers (as above), assumed and credited on French collectors’ sites as being by Baxendale, are actually by his successors and imitators.

Among his European admirers is the Swiss cartoonist Zep, who drew a portrait of Baxendale for a French site, and his own version of Eagle-Eye (above) on his Zeporama website as part of his ‘family tree’ of formative influences. Zep’s phenomenally successful mischief-maker Titeuf (briefly translated in The Dandy as ‘TooTuff’) can be seen as a direct descendent of Baxendale’s comedic kids, but often taken into more risqué subject matter than UK publishers would permit. The Netherlands also welcomed Baxendale into their top weekly Eppo which ran 16 brilliant brand-new Willy the Kid, or “Willie de Kid” strips in 1979-80, which, so far as I know, have never been compiled or put into English (1979: Issue Numbers: 41,42,45,47,52. 1980: Issue Numbers: 2,7,12,14,17,25, 29,31-33,37 (below is the cover of his debut issue).

For your enjoyment, I am re-presenting below the main contents of both of my Escape interviews with Baxendale below. Before getting to this, though, it is high time that I correct a 2007 obituary which The Guardian newspaper asked me to write for Ian Gray (1938-2007), a Beano and Dandy scriptwriter. In compiling this, I was led astray by relying on the transcript of an interview with Gray, made for BBC4’s Comics Britannia television series and kindly provided by the programme makers. As it turned out, Gray’s recollections were distinctly unreliable and so I mistakenly credited him with devising stories for Baxendale from early in his Thomson’s career, and for Davey Law and Ken Reid during this period too.

This turns out to be completely wrong. Baxendale has since advised me that “Ian Gray started work as a trainee sub on The Beano staff in the summer of 1955, aged 17. He was not allowed to write plots, storylines or anything.” The first episode of Comics Britannia was broadcast in 2007 only a few days after Gray’s death. Significantly none of his exaggerated, unsubstantiated claims appeared in the documentary. I can only apologise for these serious inaccuracies in Gray’s obit and for trusting without verifying his account of his contributions. So with this, let the record be set straight.

Paul Gravett:

When you created your Beano characters, did you imagine them still running today?

Leo Baxendale:

Yes, I meant them to stand for decades - this was my life’s creation. I didn’t envisage drawing them myself till old age. I used to say that I’d retire from drawing at about 55 - I was 22 then. As a kid in the 1930s I liked sharp-edged comics like Weary Willie and Tired Tim, the spies Serge Pants and Prince Oddsocks. They all had sly faces; I didn’t like Roy Wilson’s twee smiling faces. I preferred something a bit more daft, like George Wakefield’s comics or Dudley Watkin’s early Lord Snooty‘s and Desperate Dans - very funny and quite grotesque. I didn’t sentimentalise my characters at all.

But it was seeing Davey Law’s Dennis the Menace that made you decide to approach The Beano with your work?

Yes. Up to that very day I’d been planning to send samples to book publishers. When I saw Dennis in The Beano, I thought, ‘This is so contemporary looking. If they’ll print this, they might want my stuff!’ If it hadn’t been for Dennis, I wouldn’t have approached The Beano, because the rest of it was stuck in the 1930s. Davey Law was a brilliant stylish illustrator, but he did faithfully follow his scripts. Dennis was a Scottish production - he was allowed to be bad, but he always had to be punished at the end. That never crossed my mind. When I drew The Bash Street Kids, they weren’t punished most of the time and everyone else got marmalised!

I gather The Bash Street Kids was originally titled When The Bell Rings? [The original art above from a 1955 episode, owned by Thomson’s, was exhibited in the Rude Britannia exhibition at Tate Britain in 2010]

That’s right, but I always thought of them as Bash Street. So did the Thomson journalists and the fan letters, so after a few years [in 1956], we changed the title. Although I called them The Bash Street Kids, I never had them bashing each other in the face. They’re violent in that they’re totally uninhibited, but unlike in real life, Bash Street is a world of innocence. But if they were talking to Teacher, I’m congenitally incapable of drawing two characters just talking to each other. So Plum would be leaning his elbow on Chiefy’s capacious stomach. Similarly, if Teacher was telling the kids something in class, they wouldn’t just sit listening, they’d be cutting Teacher’s tie off or pouring treacle or ants inside the front of his trousers.

Even with Minnie the Minx, who was truly violent, I wouldn’t have her just thumping a boy in the face. It’s too crude. I’d have Minnie with her scything punch that went round three boys’ jaws in turn and she’d be standing on somebody’s hoof with one foot, kicking somebody else up the bum with her other foot, and she’d still be left free to bite somebody with her teeth! And she probably had her pet frog up her jumper too, blasting Minnie’s victims with a peashooter! There was no limit to what you could do!

I know you admire the detailed cartoons by Carl Giles in the Express newspaper, compiled into best-selling annuals each Christmas. [The example above, dated January 13th 1953, inspired The Bash Street Kids]

I collected all his books. Actually, I think he stopped drawing them himself in 1958! I know his work very well and if you have a seeing eye, you can see the bones under somebody’s drawing style, the draughtsmanship, their habits, thousands of things. Giles did an enormous amount of drawing from life in East Anglia and London, so there’s a lot of observation underneath it. Suddenly in 1958 all his cartoons began to be drawn by these two ghost artists. I wondered what had happened, I knew he had trouble with his eyesight, so I wrote to the Express to find out. I got a very indignant letter back, saying it was nonsense, Giles still draws for us. But I can’t believe it suddenly deteriorated in 1958 and he lost all his ability and knowledge of drawing from life. I’d love to find out!

You’ve never drawn from life yourself. Do you regret that?

No, it doesn’t matter,because I’d hardly do backgrounds at all, if I could get away with it. Only a minimal bit of desk and door for a classroom. I bore right in on the characters’ faces, which is what I’m good at.

So how did Giles’ influence you?

The main thing about Giles, those early Warner Brothers animated cartoons like Daffy Duck, and Tony Hancock and The Goons on the radio, they were all so uninhibited. I was uninhibited myself and because they were then very recently successful, I knew my personal approach was likely to succeed too. If nothing had appeared like that, I could have been unsure whether anybody would want my stuff. So they pulled the restraints away from me. It was more a sense of encouragement from them than actually basing myself on them.

Part of your approach was to make more use of speech balloons. Before you they had always been very terse and stilted.

Yes and often they simply told readers in a rather babyish way what the character was doing, which they could see already! I can’t claim credit for originality. I was influenced by Richmal Crompton’s Just William books. She had him talking in a daft colloquial way - and more so Tony Hancock on the Archie Andrews radio show. I loved his ratty dialogue. I just bunged it all in.

I’ve always loved the way you put words like ‘GONE’ or ‘PROUD’ and the signs and puns in your strips.

I put words all over the place in the very early Bash Streets. I remember Ken Walmsley, the Beano Chief Sub-Editor, making a snide remark about them. He said, “Look, you’ve got Minnie’s dad eating rice pudding and you’ve written rice pudding on the plate! It’s a bit of an insult to the intelligence of The Beano readers.” But I said, “No, I’m carrying on doing this because I think it’s funny.” You didn’t need the words because you could tell by their facial expression how they were feeling, but it was even funnier if you put an arrow pointing at somebody’s bum saying ‘Throbbing Pain’! (Laughter) Posy Simmonds in The GuardIan does it too and she’s a very elegant cartoonist. I wasn’t the first to do it, but I did it in such an avalanche it became very noticeable. The words were as important to me as the drawing.

You also exaggerated the sound effects.

Yes. Rather than this stylised Billy Bunter ‘Yow’ or ‘Ouch’, I tried to reproduce an actuai shriek of agony, ‘AAAArrrrgggghhhh!!’ and all the other sounds. I synthesised things very rapidly - you’re not John Milton pondering for months, you’ve got to be fast, that week, that day, so you make quick decisions.

Were you conscious of creating for children?

Only when I first thought of which strips to create. But doing weekly strips, if I burst out laughing, I knew ‘That’s it’. They were supposed to be 1950’s kids, but I didn’t know any. I had two younger brothers but I was up in Dundee and far too busy to notice what kids were doing. It all came out of my head. Childrens’ comics give me enormous freedom, there’s no inhibition. Of course you can’t do hard porn! But apart from that, I can do what I want. If I changed to a teenage or adult market, I’d have to slant my work. The people who want my stuff are the kids. They buy it themselves or nag a parent to buy it for them.

Did Thomson’s ever try to curb you? Because your stuff certainly upset their traditions.

George Moonie, The Beano editor, was fearful and wrote me some timorous letters at first, but I ignored them. The DC Thomson worriedness soon disappeared when fan letters started pouring in and the circulaiion went up. If you created successful characters, you had the freedom. And anyway, I was a very arrogant young man and wouldn’t have tolerated any little suggestions! R. D. Low, then the Managing Editor, didn’t like my work. He was about 30 or 40 years older than me and he loved Korky the Cat. I was in his office one day and he told me, “This is how a cartoon character should be” and he walked about his office, imitating Korky’s strutting walk, with his chest puffed out like a robin! He was only seized for a moment, then he went back into his normal professional self! Despite what he felt, he was a hard-headed realist and my stuff sold his comics.

Dare I ask, do you have a favourite character?

I can name one and name another. Little Plum because he wasn’t stereotyped, he had all kinds of complexities and inhibitions. I liked drawing Plug, he was lovely. I made him a big goof, he was so damned ugly and yet he’s always sure of himself in his own mind. No matter how gormless he looks, he’s always blissfully content.

Here’s an original page for your IPC creation Nellyphant. How much original artwork from your comics do you have?

Nothing at all from Thomsons or IPC. When they buy artwork from you, they still claim total ownership. You get nothing from reprints or sales abroad. But I was too busy back then doing next week’s work to think about the previous originals. As a young professional, that incessant pressure doesn’t half hone you up. But there’s no finite limit where people say you’re doing too much. It goes on piling on and when you go beyond a certain point, it becomes destructive.

You left Thomsons in 1964 and joined Odhams to create a new comic, WHAM! What made WHAM! different?

Just before I’d left, I drew a Bash Street strip with Plug’s face on a Loch Ness monster! I really enjoyed that and wanted to do more monsters, so I did Grimly Feendish and others, full of all this creepiness. Ken Reid did it too when he created Frankie Stein, that grotesqueness. And George’s Germs and The Barmy Army went even beyond The Beano in sheer imbecility! There was some lovely stuff in WHAM! and it had posh printing like the Eagle. But it wasn’t as good as I wanted it to be. I didn’t get the people I wanted or the time. Odhams didn’t have a long-term commitment to comics. It would have been different if they’d offered to set me up with a studio of young artists to produce something to last 30 years.

You went on from Odhams to Fleetway, later part of IPC.

Yes and during the next ten years I created strips like The Swots and The Blots, Sweeny Toddler, Clever Dick and then in 1975 I dropped them all to concentrate on an 8-page pull-out comic for Monster Fun called The Badtime Bedtime Book, my last work for IPC.

You did 21 of these inspired parodies, with titles like Robinson Gruesome (above) and Moby Duck, and then you left comics to do the Willy the Kid books, one a year like an annual. For the first time you owned the characters, kept the artwork and had the time and space to do your best work.

That was the great thing about the Willy books. If I got an idea that made me heave inside at the thought of it, I could run with it and build it up to as many pages as I wanted. In the comics I would have run out of space. And with Spotty Dick I could do even more lunatic surreal things!

After your memoir, A Very Funny Business, in 1978, you seemed to disappear. What have you been doing since?

I carried on Willy the Kid and his baby brother Basil in the Dutch weekly Eppo till 1980, new strips drawn in black and white and coloured by a Brussels studio. And for the last twelve months I’ve worked on a 3 foot by 2 foot Baby Basil Wall Comic. It’ll be the first time my work’s been printed same size, so no detail will be lost. In future there aren’t going to be great tidal waves of new comics, but each piece will be a vintage job. Over the years I’ve filled notebooks with scripts. One called ‘Willy the Kid Meets God - or Heavens Above!’ is probably the single funniest script I’ve ever written. I’ll probably never draw it, but I can imagine getting somebody else to draw a book scripted by me. I’ve also been writing an enormous new book, The Beano File, which goes into depth about the creative process of cartooning and has more autobiographical detail than A Very Funny Business.

And over the last four years I’ve been working on my court case against DC Thomson’s. I’m asking the High Court to declare that the copyright to all my Beano characters- Bash Street, Minnie, Little Plum and the others- belong to me and should be returned to me. It’s never been done before in Britain. The only example I know of is the case of Siegel and Shuster, the creators of Superman, in America. If I win, I’ll secure my characters for the future and get paid for the years they’ve been used since I left.

You could do an awful lot with your characters.

Oh yes, successful British comic characters have been underexploited. The Beano characters have never appeared on TV or film and I know producers who’d love to do them.

You seem to be full of ideas, while IPC blame the current decline of their comics’ sales on the recession, video games and computers and on there being fewer kids born. What do you think of today’s comics?

Obviously they’re a lot blander than when I was drawing them. People poured themselves into it then, there was no pussy-footing, no toning down, none of this bland pasteurised stuff. Also I think the page rates for comics have fallen behind since the 1950s relative to inflation. Consequently a different kind of drawing has crept in, more like pocket cartooning, quicker, zippier to do.

How do you feel about artists who draw in your styles?

There’s quite a difference between the natural process of young artists who model themselves on somebody more mature whom they admire, then developing their own style, and those who ghost - being told by publishers to slavishly follow somebody else’s style. That inhibits the artist because he’s stuck in jelly and it’s not good for the characters.

How do you think comics will change in Britain?

I’m not sure what’s going to happen, but it may not come through ordinary comics in newsagents being transmogrified, something else may happen. For myself I’m doing something new, the case against Thomson’s. It’s a creative effort going on, but it doesn’t necessarily have to happen in the same old way. For example, Steve Bell wrote to me in 1977 when he was still a teacher in Birmingham. He sent me a load of his drawings and a sentimental story about a humanised train. He said he was thinking of launching into the unknown world of the freelance cartoonist and asked what I thought. I wrote back that I thought he was a splendid artist but he should try something a bit spikier. Then I didn’t hear from him for a while, and suddenly he wrote to tell me he’d taken the plunge. And then he was drawing Maggie’s Farm in City Limits and If ... in The Guardian, a magnificent thing! So you see you never know where things lead. He hasn’t ended up revolutionising The Beano or IPC, it’s happened in The Guardian. You can still see his Beano influence, he still draws those belly-buttons on his penguins like I did on the bears in Little Plum!

Following Ken Reid’s death on February 2nd 1987, I interviewed Baxendale again and started by asking him about Reid’s special quality.

Ken Reid’s finest creations for children’s comics (and these were adult characters - in particular Jonah and Jasper the Grasper) had a quality of intensity of comedy. Such intensity is a drain on the nervous system, and Jonan took a toll on Ken. The ‘all-time great’ characters of comics history are generally marked by longevity. Jonah ran for only six years, but that was by quirk of circumstance. Jonah, an incandescent creation, and the immortal “Aghhh! It’s ‘IM!” live persistently in the mind.

How did your lawsuit finally work out earlier this year?

In my case against D.C. Thomson over the copyrights to my creations - Little Plum, Minnie the Minx, The Bash Street Kids, The Three Bears, The Banana Bunch (above) - I was heading from a three-week trial in the High Court from June 27th 1987. There were always several possible endings - like those role-playing books! But in the end we came to a mutually acceptable settlement in late May. I was fighting with Legal Aid and if anybody on that system is made a serious offer, it must be considered, because of the enormous costs to public money to go on fighting. The terms are confidential but I now have an amicable association with Thomson’s.

How did your new book Thrrp! for underground comix publishers Knockabout come about?

Gilbert Shelton, creator of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, reprinted Spotty Dick in Rip Off Comix #8 (above) and after it went down very well, Tony Bennett of Knockabout asked me to do a Spotty Dick book. In Thrrp! there’s no dialogue, because then we can re-publish around the world. And I used easily recognisable plots, like Milton’s Paradise Lost and Aesop’s fable, The Tortoise and The Hare (below). I didn’t want a word for the title either, so I chose Thrrp!, the sound of blowing a full-blooded raspberry, like in The Goon Show - I can’t do them myself!

What inspired your story in Thrrp!?

I conceived Spotty Dick originally as a young lad who’d left school and kept losing jobs because he had a tiny brain and big feet. But as time went by and we had massive unemployment, it didn’t seem right somehow! For Thrrp! I’d been thinking about these inhabitants of Planet Url, they’re all conformists - not unlike our own Earth. And I realised how beautifully Spotty Dick would fit into this, as he’s a deviant - not that he does it on purpose, he’s just too thick. He makes a lovely contrast, blundering through life, stumbling into plots.

I love Spotty, I think of him almost as a child. Like Little Plum, he’s quite complex, definitely not a hero, but not quite a loser either. Plum was a character that lightning always struck twice. But he was a survivor; even if he was a bit dim, he’d usually contrive that it was the others around him that got clobbered and not him!

Are you aware of how much your work has influenced other comics creators?

Yes. After A Very Funny Business in 1978, I got a fan letter from Alan Moore, who was just starting his career. He’d imagined that pros like me rattled off five pages before breakfast and was so relieved to read that I got tired and did stupid things because of lack of sleep. Alan Moore, Steve Bell, Savage Pencil and others have taken the ethos of my work, The Beano Spirit, that uninhibited outlook, and they’re carrying it on in their own work. I think that’s wonderful.

To conclude, here is Baxendale’s eloquent and poignant ‘Preamble’, remarkable as almost a Manifesto or Credo, written for his exhibition announcement. It’s an exhibition which his countless admirers eagerly await and which must be realised:

I am an artist.

Every child, man child and woman child, is born with the capacities of learning and synthesis, that together make creativity possible.

Whether those inborn capacities are translated into professional capability is dependent on circumstance. Circumstance, more of than not, will be determined by the controlling system in which we live.

As an artist, I have had a companion, Comedy, to nudge my elbow and point out the dangers of the straight and narrow.

This exhibition is a staging point in the struggle between Comedy and Anti-Comedy.

The antithesis of Comedy, Anti-Comedy is the domain of the one-eyed brothers Capitalism and Patriarchy, who walk hand in hand.

I do not believe that it is possible to carry through a lifelong struggle against almighty power by intellect alone: I believe it is necessary to walk through the valley of fire (in my own case, as it turned out, repeatedly.)

Posted: December 30, 2013