Keiichi Tanaami:

Manga and Pop Art

The most vivid childhood experiences can implant indelible impressions. In the case of Keiichi Tanaami, born in 1936 in Tokyo, they were enough to fuel a lifetime of diverse, determined self-expression in a wide range of media, from psychedelic Pop art paintings and experimental animation to designing the Japanese editions of Playboy (‘Wonder Girl’ spread from 1968, below) and record albums by Jefferson Airplane and The Monkees. Some of Tanaami’s sharpest memories have haunted him since the Second World War. As a boy he witnessed and survived the American air raids which decimated the capital, their firebombs lighting up the night sky and shimmering through his father’s goldfish tank. These distorted, brightly coloured creatures have become one of his recurrent symbols.

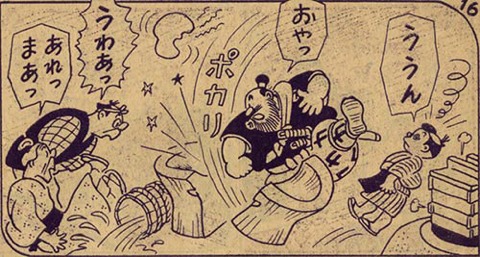

Equally potent influences were the comics or manga which the young Tanaami eagerly consumed and imitated. Launched in January 1948, the monthly boys’ magazine Manga Shonen was a particular favourite. “I couldn’t stay calm on the day it was coming out, so I’d wait for hours in front of the bookstore for the new issue to arrive.” Among the fresh postwar talent to blossom in its pages was Osamu Tezuka, who would be later hailed as Japan’s ‘God of manga’. Tanaami was absorbed by the techniques in Tezuka’s first full-length magazine serial Jungle Emperor in Manga Shonen (below) : “His panel layouts adopted the way of developing the scenes in a film and resembled real motion pictures. I made lots of my own manga, but lost them all. Due to food shortages and the lack of entertainment after the war, the world of manga became a kind of safe shelter for me.”

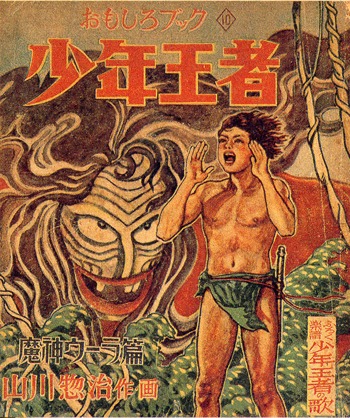

Tanaami was also captivated by the period’s vigorous text-driven picture stories or ‘emonogatari’. A favourite was Shonen Oja (‘King of Boy’) by Soji Yamakawa (Shonen King cover from December 1948, below and interior page from later reprint). This courageous junior Tarzan was originally conceived for a pre-war ‘kamishibai’ or illustrated storytelling show performed for children by touring confectionary vendors. In 1946 it was released in book form and became the genre’s first post-war bestseller. Tanaami recalls, “The techniques of Yamakawa’s pen drawing overwhelmed me. The main character is a Japanese boy brought up by a gorilla. I was so into sketching animals that I wouldn’t do my homework, so my mother was always telling me off.” In 2008, Tanaami paid tribute to Yamakawa, as part of the artist’s centenary retrospective, through a series of limited edition silkscreen prints (see below, 2008 print in an edition of 25).

Despite his obsession with comics and his monthly lessons from his father’s friend Kazushi Hara, a successful manga professional, Tanaami went on to study at art school. Bored with classes, he made frequent visits to the Iena-shoten store in Ginza, the one place were he could buy Sixties American comic books and find out through magazines about the Pop art they inspired. His discovery of Robert Crumb’s LSD-triggered underground comics was another epiphany: “Crumb’s ‘comix’ all communicated strong messages about breaking down social order. They totally changed my understanding of manga. With his themes of anti-society, sex, violence, etc., every panel was permeated with a visceral smell and completely devastated my weak mind.” (See Tanaami’s 1971 animation Good Bye Elvis and USA below).

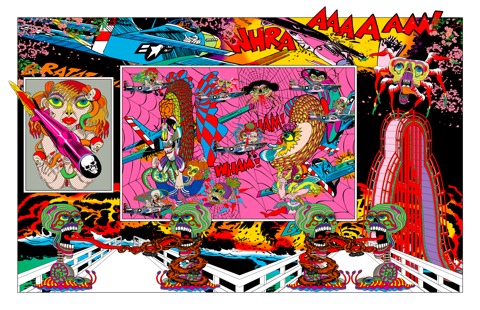

Still very active as he approaches eighty, Tanaami showed again at ArtBasel Hong Kong this year and is working on new animated films and is halfway through a book of paintings based on Shozo Numa’s Kachikujin Yapoo (‘Yapoo the Human Cattle’), “the best weird novel of modern times”. His new piece below for ArtReview Asia magazine (below) starts from “a big spider, ghastly and smiling above my head when I was recovering in bed from catarrh of the colon.” ‘The Laughing Spider’ pulses like some feverish brain scan of Tanaami’s synapses firing and mapping a web of flashbacks, from Mickey Mouse cartoons in a seedy cinema or a Showa period red-arched bridge to Lichtenstein-style bombers, burning skin and those goldfish. “All these memories came up into my mind so clearly, as though they happened yesterday. Manga-ish conception, manga-ish composition, manga-ish thought - I love them all!”

‘The Laughing Spider’ for ArtReview Asia Magazine

Click images to enlarge.

Web Exclusive:

Here’s the full email interview which Keiichi Tanaami kindly replied to:

Paul Gravett:

How have manga been perceived in Japan in the contemporary fine art world? Are they becoming more accepted, even respected, as a valid artform in their own right?

Keiichi Tanaami:

Considering that the creators who grew up with manga are becoming famous as artists, the influences on them from manga cannot be ignored both in their work and in their thinking. It’s a common experience for the thoughts and messages in manga you have read in your childhood to be stored in the brain and suddenly appear today. Supposedly, this does not apply simply to the forms of manga, but also to the visions of manga locked in one’s subconscious, which can erode the territories of art.

Japanese comics - or manga - and picture stories - or ‘emonogatari’ - were among the biggest visual influences on your childhood. Which artists and heroes did you most enjoy as a boy and why?

When all is said and done, it was Osamu Tezuka’s manga which really absorbed me during that period. His panel layout adopted the way of developing the scenes of films and looked as though it was real motion pictures. My heroes of emonogatari were Soji Yamakawa, known for Shonen Ohja, and Shigeru Komatsuzaki, famed for Daiheigenji (cover, above). The main character in Shonen Ohja is a boy brought up by gorilla. The techniques of his pen drawing overwhelmed me.

What kind of comics of your own did you make, when you were growing up?

I was so into sketching animals that I would not do my homework, so my mother was always telling me off. I made lots of my own manga, but lost all of them. Some would have survived, if not for the war.

I read that you knew a professional mangaka named Kazushi Hara when you were young? How did you meet him? What did you like about his work?

Mr. Kazushi Hara was a friend of my father’s since he was a university student. I visited him with my works once a month, and he gave me lessons and tasty snacks. At that time, he was working on the serial manga Kanra-Karabei (above), a popular work which made him into a big star as popular as Osamu Tezuka. I carried on visiting him until he died of tuberculosis. I still believe this was a very precious time. His elaborate hand-drawing won my admiration.

Did you seriously pursue the idea of becoming a mangaka? Do you think you could have worked exclusively as a mangaka or would you have preferred to try many other things as well?

In my childhood, there was a comic magazine Manga Shonen (above). I could not stay calm on the day it was coming out, so I stayed for hours in front of the bookstore to wait for the new issue to arrive. My enthusiasm for manga was almost crazy, as I was drawing manga all day instead of doing my studies. Due to food shortages and the lack of entertainment during the aftermath of the war, the world of manga was a kind of safe shelter for me. For several reasons, I did not become a mangaka, but manga lives on as the basis of my expression and brings with it a huge darkness.

Back in the Sixties, did you know some of the avant-garde, experimental manga creators in Garo magazine, like Sanpei Shirato, Yoshiharu Tsuge, Suehiro Maruo or Seiicihi Hayashi?

Garo magazine was my favourite. It had provocative contents, such as the nonsense that comes from ignoring stories and non-verbal expression and so on. So most of the Garo comics were avant-garde. Since it was launched, Genpei Akasegawa and Seiichi Hayashi (below) have been my friends, we were classmates at art school.

Can you describe and tell me more about that one special shop where you could buy American comic books? I gather Wonder Woman was among your favourites? (Below is a piece from your Hop Step Jump inspired by the superheroine.)

The bookstore was called Iena-shoten located in Ginza and it was the most exciting place. I went there many times a week when I was an art student. It was incomparably more stimulating to my imagination than the boring lessons at the university. In addition, I discovered the rise of American Pop art through art magazines. Though I could not read the text, I felt something extraordinary and my dream became bigger.

When did you discover the work of Robert Crumb and the whole American underground comix scene and what effect did it have on you?

One of the things which represent the Sixties’ New York underground scene is Robert Crumb’s comix. They were poorly printed so the ink came off on your hands, but they were all communicating strong messages about breaking down the social order. They had great power which totally changed my understanding of manga and strongly stimulated me. With his themes of anti-society, sex, violence etc., every panel was permeated with a visceral smell and completely devastated my weak mind.

What happened with the movie version of Kachikujin Yapoo that you were art-directing? Did you admire or refer to the manga adaptation of this decadent novel?

Currently, I am working on a book of paintings based on Kachikujin Yapoo. It has been almost two years since this was planned, but it is still only halfway. Reproducing this novel – called the best weird novel of modern times - in paintings is so difficult, it makes me feel I am reaching my limit. There are some manga versions of this novel, but the expression of the racism, perversion and mystery in the original were not depicted well nor interestingly.

How do you feel about making this brand new comic story for ArtReview Asia magazine?

This comic projects memories that have impressed me from my childhood: US combat aircraft; Disney animation which I saw at a seedy film theatre; the light of flares reflecting on the scales of goldfish in an aquarium; a big spider, ghastly and smiling above my head when I was recovering in bed from catarrh of the colon; pale pink cherry blossom in the night; hot wind of the bomb attack burning skin; the red arched bridge next to the hotel called Dragon Palace from the Showa period. All these memories have risen into my mind so clearly and vividly as though they happened yesterday. So, it was great fun to work on this project! Manga-ish conception, manga-ish composition, manga-ish thought, I love all of these! My expression will become more manga-ish, as I am also still working on animation (see his 2013 animation Adventures in Beauty Wonderland on nowness below).

Adventures in Beauty Wonderland on Nowness.com

Posted: September 7, 2014This Article originally appeared in ArtReview Asia Magazine Vol. 2 No. 2, Autumn & Winter 2014.