Katsuhiro Otomo:

Post-Apocalypse Now

As The Japan Times recently put it, ‘Without Akira there would be no ‘Cool Japan’.” Manga get taken for granted today, widely available as English paperbacks and inspiring global artists with their dynamic styles and techniques. But twenty-five years ago, what would become a tsunami of Japanese comics was barely a ripple. In May 1987, independent U.S. publishers First and Eclipse instigated the first wave by serving up lengthy historical epics Lone Wolf and Cub and Kamui, among others, in monthly or fortnightly slices as American comic books. But the big impact came in 1988, when Marvel’s creator-owned imprint Epic unleashed Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, in prestige, squarebound comics. His black-and-white pages were put into colour, making the first use of a vibrant, sophisticated computer palette devised by Steve Oliff (below). Here was a gripping, fast-paced science fiction manga that would truly cross over to Western audiences on a massive scale. Akira would send shockwaves worldwide.

Echoing the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Otomo opens Akira with the detonation of a mysterious bomb over Japan, triggering a Third World War. Thirty-eight years later, the world of 2030 is rebuilding and a sprawling Neo-Tokyo rises from the ashes, besieged with biker gangs and anti-government terrorists. This future belongs to a new breed of human being, capable of deploying unprecedented inner energies but at a terrible price. A secret military agency wants to harness these gifts for its own ends, but the fragile mind of the child-like Akira, the most powerful and temperamental of these ‘Espers’, cannot be contained. Psychic forces, seismic urban destruction and physical deformations surge out of control, threatening to plunge the city into a second apocalypse of its own.

Akira was cyberpunk before cyberpunk, when Otomo began serialising it in 1982 in the bi-weekly Young Magazine. He would not come across William Gibson’s seminal 1984 book Neuromancer until 1985, when it was translated into Japanese. Instead, Otomo cites the novels by Seishi Yokomizo and their preoccupation with ‘new breeds’ of humans mutating to adapt to volatile conditions, personified in Japan’s mistrusted rebel youth and rioting students of the Sixties. Born in 1954, Otomo sought to evoke this volatile period he knew well in the future-world of Akira. “I wanted to revive a Japan like the one I grew up in, after the Second World War, with a government in difficulty, a world being rebuilt, external political pressures, an uncertain future and a gang of kids left to fend for themselves, who cheat boredom by racing on motorbikes.” He also pays tribute to his childhood favourite manga by Mitsuteru Yokoyama, the giant robot classic Tetsujin 28 Go (1956-66), released as an animated cartoon in America as Gigantor, and to the lasting impressions on him of American films such as Easy Rider and Bonnie and Clyde.

Akira was also a ‘new breed’ of manga - faster, stronger, smarter, and more naturalistic. American comic book fans hooked on Neal Adams, John Byrne and Frank Miller were not yet ready for the alien distortions and large-eyed caricatures of more typical manga, but they were blown away by Otomo’s detailed realistic fantasy. His innovative approach grew out of his studies in draughtsmanship and architecture and his admiration for the meticulous locations in the manga of Shigeru Mizuki (published in English by Drawn & Quarterly). As for those ‘normal’, unexaggerated eyes, he started by using his friends as models for his drawing. “My style took shape naturally by observing them. I try to draw things as true as possible, without falling into mannerism.”

Another crucial ingredient to Otomo’s style was the aesthetic shock in the late Seventies of discovering the work of France’s master of science fiction comics, Moebius, alias Jean Giraud. “At the time, manga was confined to the real, the everyday, the concrete, the social. Everyone swore only by ‘gekiga’, the adult version of manga which used lots of frames and sombre compositions. The clear yet very expressive and detailed line of Moebius was a real revelation. A fantastical universe like that of Arzach pushed us out of our routines. I was far from being the only one to be influenced. Many manga authors took it as an invitation to immerse themselves in new worlds, to open up fresh artistic perspectives.”

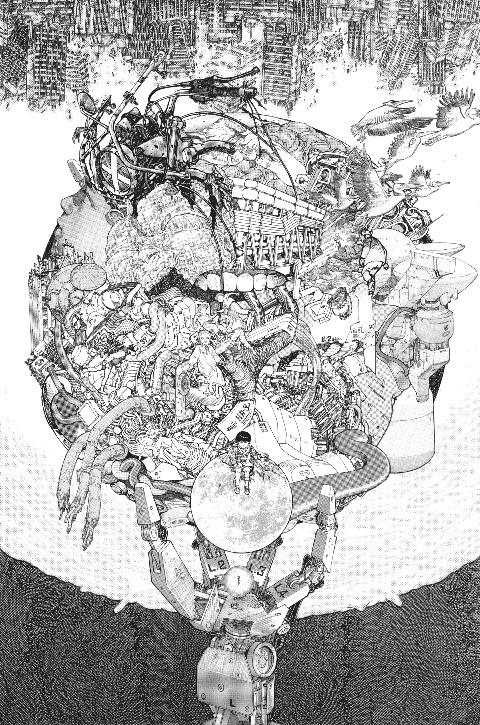

The distinctive look of Akira greatly helped it to cross language and culture barriers and implant manga internationally. In Japan, the instant success of the first volume of Akira in a special, oversized, high-priced format at 1,000 yen, selling out immediately of two print-runs totalling 300,000 copies, led to Otomo being commissioned to direct his own animated movie version in 1988. Alongside manga, he had been working in the anime field since 1983 and getting noticed and praised. Granted complete control to bring his epic to the big screen, he created a hugely innovative production, advancing the state of the art of adult animation to unprecedented heights. He had not finished his manga story at that time, so he had to come up with an ending for the film. Despite running well over budget, Akira the movie and Akira the comic reinforced each other’s success and worked as highly effective ambassadors for Japan’s increasingly cool pop culture exports.

For its original magazine serialisation, Otomo was expected to produce a twenty-page episode every two weeks, which put great demands on him. “My method was to completely draw the first page as a warm-up without preparatory sketches, directly on the final board, with no reworking, to get going as quickly as possible. Once that first page was done, an assistant inked the decors and buildings with a Rotring pen and ruler. Meanwhile, I pencilled the following pages, finishing usually two days before the deadline. I then needed half a day to draw all the characters, then I gave a finishing touch to the buildings by trying to instill them with life and expressiveness, with dust, cracks, broken windows. I’d finish the last pencils on Sunday at 5am, the inking of the characters by 7pm, and the episode was delivered Monday morning at 8am.” After the movie version, Otomo resumed his manga version and unfolded his much longer, richer, more complex vision, completing it in 1990. With many more characters and subplots, it finally filled six albums of around 400 pages each, released first in English by Dark Horse and currently by Japanese publishers Kodansha.

Otomo’s other works, in comics and in film, before Akira and since, are well worth exploring. Otomo began getting his comics published in 1973, mainly for Manga Action magazine, but avoided science fiction until he switched more to rival title Young Magazine, where he left his first stab at the genre, Fireball, unfinished in 1979. In many ways, his follow-up, Domu: A Child’s Dream (above), serialised from 1980 and published as a single volume in 1983, is a more accessible entry point than Akira. Let’s hope Kodansha will put it back into print in English shortly. This chiller presages Akira by focussing on a battle between psychically empowered tenants of a crowded, run-down apartment complex in present-day Tokyo, one the senile Old Cho who is murdering tenants, the other a young girl named Etsuko determined to stop his killing spree. Mixing the mundane with the strange and sometimes horrifying, Domu was lined up for a live-action Hollywood film by Guillermo del Toro but has yet to happen.

In cinema, Otomo’s other achievements include his affectionate reinterpretation of Osamu Tezuka’s 1949 manga Metropolis as the screenplay for Rintaro’s 2001 anime movie version. Otomo directed a 2007 live-action adaptation of Yuki Urushibara’s folklore fables Mushishi about an occult detective in an imaginary Japanese past. Perhaps most signficantly, Otomo wrote and directed the ambitious Steamboy animated feature in 2004, realising a striking steampunk Victorian England. Sadly, it failed to set Western box offices on fire.

As for comics, Otomo keeps his hand in, creating new, mostly short pieces or even writing scripts, starting in 1990 for Takami Nagayasu who illustrated another post-nuclear-war saga, The Legend of Mother Sarah. Otomo often uses his manga as springboards for his later anime projects. For example, three of his earlier comics inspired three sections of the anthology animated film Memories in 1995, Otomo directing the tale Cannon Fodder himself. Similarly, his latest short cartoon, Combustible, part of an ensemble movie entitled Short Peace, grew from a nine-page, one-shot manga of the same name which he crafted for the January 1995 debut issue of the anthology Comic Cue. Shortlisted as one of ten nominees for this year’s Oscars, Combustible brings to vivid life the firefighters of Japan’s Edo era (trailer below).

In April 2012, to accompany an interview and features about him, Otomo created DJ Teck no Morning Attack, an original eight-page colour manga, for Geijitsu Shincho (below). It was in this arts magazine that he revealed his long-awaited return to full-length serial manga. “I’ve decided to come back to manga, because the way we produce and consume culture - books, music - is changing. I felt the need to return to an entirely manual way of working, a handmade world, while there’s still time, and without an assistant.” Otomo’s already spent some four years developing what will be his first manga aimed at an adolescent readership. His only clue - “Its setting will be the legends of medieval Japan from the Meiji era.”

April last year also brought a spectacular two-month retrospective exhibition in Tokyo, Genga (Japanese for ‘original drawings’), in aid of victims of the Japanese tsunami disaster. Thousands of visitors marvelled at all 2,300 pages of Akira suspended inside six large glass display cases, one for each volume, as if thrown into the air by an explosion. A second larger room displayed his colour artworks, pages from Domu, illustrations and advertising. And for 500 yen donation, you could get your photograph astride a replica of Kaneda’s famous red motorbike from Akira. It may be just as well that Hollywood’s mooted live-action remake has been recently abandoned. After three decades, it is Otomo’s vision which still astonishes in both comics and film. Hopefully, his many admirers won’t have to wait too much longer to read his next manga magnum opus. In the meantime, UK artist and admirer James Harvey has compiled a brilliant infographics timeline of Otomo’s output - which shows there’s plenty more by him still awaiting translation!

This article originally appeared in Comic Heroes Magazine #19. Studio photo from Geijitsu Shincho Magazine.