Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella:

A Landmark in Adult French Comics

“Barbarella, look after your little boots,

And just tell me once and for all,

That you love me, or else,

I’ll send you back to your science fiction.”

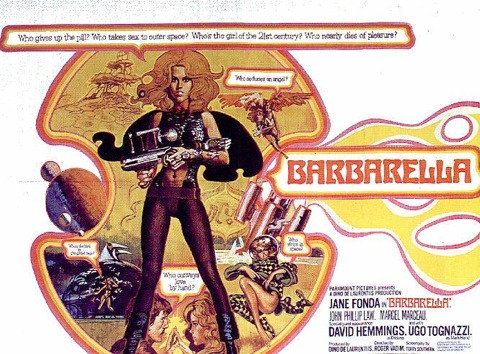

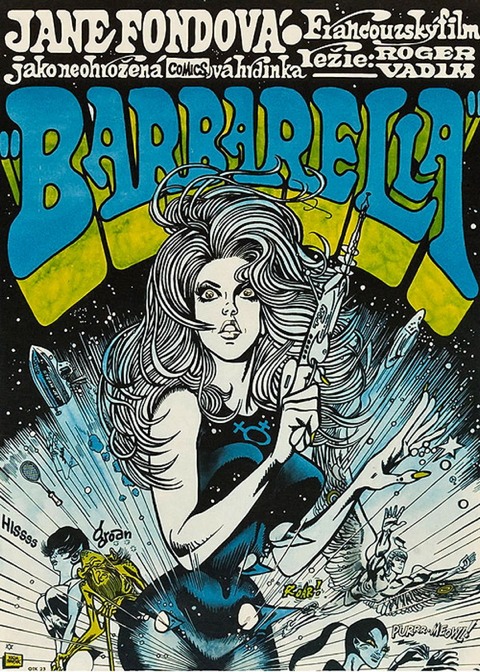

It’s a sign of how “in” and cool Barbarella was in swinging 1966 in France, that superstar singer-songwriter Serge Gainsbourg devoted this whole verse to her in his hit song, Qui Est In, Qui Est Out (‘Who’s In, Who’s Out’), while only mentioning The Beatles briefly as “The lads from Liverpool.” Two years later, the English-language Roger Vadim movie adaptation, starring a 30-year-old Jane Fonda, turned the blonde space adventuress into a highly visible global symbol of the sexual revolution (below are the British poster by Robin Ray (later known as erotic comics maestro Eric Von Gotha) and the Czech poster by Kaya Saudek). Barbarella was a truly liberating creation, not only for her creator, Jean-Claude Forest (1930-1998) but also for French and international comics as a whole.

Today, France is justly famed for its abundant and sophisticated bande dessinée, or comics, culture, much of it aimed at older readers. Recognised as “the Ninth Art,” it is honoured with major gallery exhibitions and in Angoulême a massive yearly festival and state-of-the-art museum, and its writers and artists are hailed as auteurs, geniuses, and celebrities. The quality, and sheer quantity, of graphic novels have been rising year-on-year for over 12 years, stabilizing with only a small dip to over 5,000 new titles published in 2013. But it was not always like this. It’s easy to forget that France was once hostile to comics, especially those imported and translated from America, and was one of the first countries to impose strict controls on what could be published. Forest’s eight initial Barbarella adventures, compiled into an “adults-only” album in 1964, would have been subjected to these same stifling state controls and presented an important challenge to their power and relevance.

To put Barbarella’s heyday into some context we need to time-travel back to the aftermath of the Second World War. Moral panics soon broke out in many countries, prompted by fears about the future, embodied in children and childhood in general, and about rising juvenile delinquency, hardly surprising considering the societal and familial damage caused by the conflict. Rather than deal directly with the more complex roots of this problem, politicians and various interest groups sought causes and scapegoats elsewhere in the mass media, and in particular in the least defensible medium presumed to be solely for children - comics. In America, anxious to avoid legislation, the majority of publishers banded together in 1954 to finance their own regulator, the Comics Code Authority, which enforced rigorous, infantilizing limits on content. In Britain, cut-price publishers of reprints of American comic books were too small-scale and disparate to defend or self-regulate their products. Instead, pressures to take action built up on the government, which finally enacted a ban in 1955 through the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act.

France was much quicker off the mark with both a state-run regulatory commission and legislation. As early as May 20, 1947, the Communist Party proposed a legal curb on the excesses of popular American and American-style comics. Juvenile crime rates reinforced their arguments, showing that 31,000 minors had been convicted in 1946, three times the number in 1936. No enquiry arose from the proposal, but in March 1948 the government began consultations of its own to draft a law to “Organize the control of publications intended for young people.” After much debate and several redrafts, the wording for a law was passed on July 16, 1949 to prohibit any publication “Presenting in a favorable light crime, theft, laziness, cowardice, hatred, debauchery or any acts qualified as crimes or misdemeanors or of a type to demoralize children or young people.”

The day before, leading comics artist Alain Saint-Ogan had written as president of the Union of Children’s Magazine Illustrators to warn the legislators that abandoning a minimum proportion of foreign material would be a catastrophe for French illustrators. A proposed quota insisting on a minimum of 75% French material within the total output of publications covered by the law was dropped in place of a truncated clause, which made it a crime to provide minors under 18 years old publications “Presenting a danger to youth because of their licentious or pornographic character.”

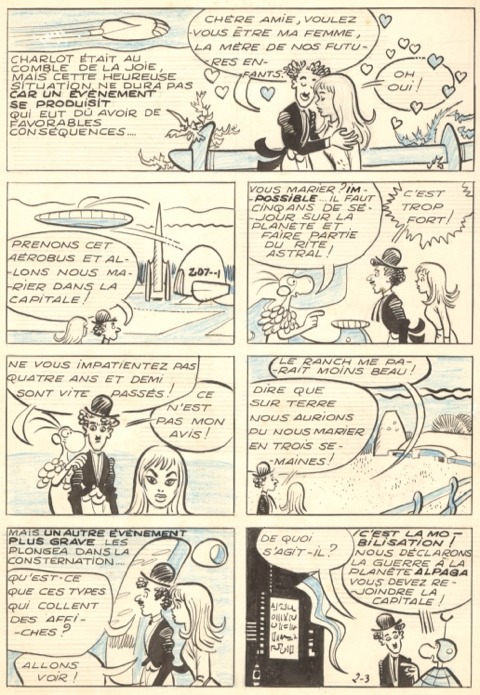

Breaking into the industry during his early twenties, Jean-Claude Forest was already well aware of the restrictions working for France’s post-War comics market, cartooning in his very lively, loose style on necessarily innocuous scripts for comedies in the Communist weekly Vaillant, later re-named Pif Gadget, or a series of Charlot albums inspired by Charlie Chaplin. In one 1960 episode (above), for example, Charlot Interplanetary Pioneer scripted by Roland De Montaubert, the little tramp falls for and proposes to a Brigitte Bardot-style woman on an alien planet. She agrees to have his future children but before they can marry, war breaks out with another planet and Charlot finds himself conscripted. Forest’s abiding love of science fiction would re-surface in further Charlot tales, from an encounter with robots to a voyage to the moon.

Forest found greater freedoms elsewhere in the science fiction magazine Fiction, launched in 1953 as the French edition of the American Magazine of Fiction and Science Fiction. Although there was no official quota requiring French content, the publishers chose not to use the original American covers and commissioned Forest to produce new French covers, in which beautiful women frequently featured. Forest also contributed interior artwork, including a profusely illustrated reprint in Fiction‘s Summer 1955 issue of Catherine L. Moore’s 1933 Weird Tales story ‘Shambleau’, about a seductive woman-like creature who, in a twist on the legend of the Medusa, hypnotizes and devours her victims by addicting them to sexual ecstasy (opening page, below). A few years later, Forest would revisit and reinvent the Medusa myth for his second episode of Barbarella.

As a collector and fan, Forest was knowledgeable and enthusiastic about American science fiction of his era and before, and not just through the French Fiction magazine. In 1958, he began illustrating nearly half of all the color covers for Hachette’s science fiction imprint Le Rayon Fantastique (below), veering between surreal abstraction and more traditional imagery, again often incorporating attractive female forms, in the earlier tradition of America’s great pulp magazines and continued in the comic books.

Forest’s notion in Barbarella of combining science fiction, comics, and a strong female lead had precedents in American newspaper strips and comic books. In Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, Dale Arden may have been forever ardent about Flash, but she usually played only the glamorous love interest, pining to be rescued. In Frank Hampson’s Dan Dare series in Eagle, Professor Peabody turned out to be a brilliant woman scientist, though she remained prim and proper, and entirely desexualized, because she was appearing in a British children’s weekly edited by the Reverend Marcus Morris. One attractive and active female protagonist who might well have caught Forest’s eye was Connie, an American strip created from 1927 to 1944 by Frank Godwin. His resourceful, curly-haired Connie Kurridge appeared under various names in France and in various genres including escapades in outer space.

In 1940, the New York publisher Fiction House diversified from pulp magazines into comic books, and in 1940 spun-off their science fiction title Planet Stories into Planet Comics. Women still tended to be portrayed here as cheesecake in peril with tight-fitting, revealing outfits, but a notable exception was Mysta of the Moon, “The most intelligent being in the universe.” Mysta was introduced in 1945 during the closing months of World War II, as “A slender girl, alone against the universe’s most evil force… the God of War! She, a living temple of man’s essential goodness, is his last hope!” Over the course of 28 stories credited to “Ross Gallun,” an in-house pen-name, Mysta relocated from her lunar citadel to Earth where, disguised as lowly lab “technician grade three,” Ana Thane, she battled monsters and villains, helped by her cloak of invisibility and her telepathically-controlled robot. The splash page (above) is from an episode in Planet Comics #37 drawn by Fran Hopper.

Whatever their influence, these precursors were very different from the science fiction heroine which Jean-Claude Forest devised in 1962 for Georges H. Gallet, editor of Le Rayon Fantastique list and of the men’s interest quarterly V-Magazine (a Forest interior image from Autumn 1960, and a George Pichard cover from Autumn 1962, above). Forest later recalled Barbarella’s origins. “One day [Gallet] asked me if I wanted to do a strip for him - no holds barred! Gallet had asked me to do a kind of female Tarzan, Tarzella, but that idea didn’t particularly interest me. It led me to come up with Barbarella. For the next two years, at the rate of eight pages every three months, I told her adventures, going with the flow of inspiration, without any pre-planning.” As she sprang into life on the pages of V-Magazine in the Spring 1962 issue, you can feel the freedom from censorship and self-censorship which Forest enjoyed, developing his “beautiful orchid” into a woman of intelligence and principle, sensitivity and sensuality. She is described by the one-eyed Queen of Sogo as “Venus personified” with “a face as pure as a vestal virgin’s, but she is more desirable than all the whores of Sogo.” Like an intergalactic Gulliver’s Travels, Forest’s playfully imaginative serial reveals how the crash-landed space traveller interacts with the bizarre inhabitants of the planet Lythion.

At this time, the culture of comics appreciation was gradually changing in France and Forest was involved, along with film director Alain Resnais, with the first organization of comic fans, Le Club des Bandes Dessinées in 1962. Forest was on the editorial team of the Club’s magazine, Giff Wiff (below).

Another enthusiast Club member was the Belgian-born French publisher Eric Losfeld, whose company Le Terrain Vague (the French translation of his surname meaning “wasteland”) specialized in erotic and fantasy literature. Losfeld got Forest’s agreement in 1964 to compile the V-Magazine stories into a deluxe, over-sized hardback artbook for adults only, a first of its kind for comics in France. In 1969, Losfeld recalled, “Of the 600 books I’ve published in 20 years, six got me into trouble with the Surveillance Commission, and the first of these was Barbarella.”

Under the 1949 law, the book was banned from being put on public display. Nevertheless it received rave reviews and from a modest initial print-run, it would go on to sell 200,000 copies. Barbarella proved there was an adult readership for adult comics in high-quality albums, or “graphic novels,” a term coined in that same year, 1964, by American critic and dealer Richard Kyle. The French ban on Barbarella was never lifted and for subsequent re-editions Forest would revise his artwork, making it more, or less, tame to suit the times. In the version published to tie in with the 1968 film, with Jane Fonda’s photograph on the cover, Barbarella was more covered up, while a later editions would reveal even more than the original (below). Her erotic appeal was often remarked on by the media, but to Forest this was only one aspect of its success. Bemused by this, he remarked in (À suivre) magazine in 1984, “Where I saw humor and the expression of liberty, all they saw was ‘la fesse’ (literally, ‘the butt’).”

Barbarella was the vanguard of a Sixties wave of liberated comics heroines in France and elsewhere. V-Magazine itself followed up in 1965 with Scarlett Dream by Claude Moliterni and Robert Gigi, and Blanche Epiphanie by Jacques Lob and Georges Pichard (below), while Losfeld also published hardcovers of the Pop Art adventures of Guy Peellaert’s Jodelle and Pravda. By happy coincidence, the October 1962 issue of Playboy had introduced Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder’s Little Annie Fanny, though she was typically more a reactive than active protagonist, an innocent broad abroad and closer to the dumb blonde stereotype. Barbarella arrived in America in the hip intellectual magazine Evergreen Review in 1964, and in the following issue, August-September 1964, Michael O’Donoghue and Frank Springer debuted their erotic fantasy female, Phoebe Zeit-Geist, taking inspiration from Terry Southern’s 1957 novel Candy (Southern is shown in this Dennis Hopper photo below, on the beach on a Sunday in Malibu in 1965, while hanging out with Robert Fraser at Fonda and Vadim’s house). Southern was a natural choice to go on to write the Barbarella screenplay.

Among Barbarella’s other “sisters” are Valérian’s feisty companion, Laureline in France, Vampirella and Sally Forth in America, and Modesty Blaise, Varoomshka, Oh! Wicked Wanda, and Scarth A.D. 2195 in Britain, Satanik, Jacula, Isabella, and Valentina in Italy, and the fictional Russian Amazon Octobriana (she was actually adapted from a Czech project). It is hard to ignore the fact that all of these characters were created by men, although Trina Robbins designed Vampirella’s revealing costume and writer Jo Addams scripted the Scarth newspaper strip.

So it’s significant that the Humanoids’ new editions of Barbarella (in a Collectors’ Edition this year, and next year a smaller-format collection of the first and second French albums) welcomes a woman’s creativity to the work in Kelly Sue DeConnick’s engaging adaptation. DeConnick’s contemporary spin on Forest’s script remains appropriately flirty and camp whilst providing a fresh perspective, ensuring that Barbarella remains as important a symbol of feminism as she was over fifty years ago. Strong, independent, sexually liberated, yet with a touching fragility, Barbarella is more than just a pin-up, she’s a fully rounded human being.

Jean-Claude Forest (above) went on to create many other characters and masterpieces, but Barbarella transformed his work and his life. Right to the end, he was busy as a consultant on a proposed animated version from Nelvana, and as a collaborator with Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier on a new American Barbarella comic book. Today, after plans for a re-make of the movie by Robert Rodriguez fell through, a television series is in full development with acclaimed filmmaker Nicolas Winding Refn (Drive) attached as a producer. It’s never too late to discover, or re-discover, Forest’s iconic creation – a bright, beautiful star, forever fresh and free-spirited.

Posted: September 25, 2014An edited version of this Article originally appeared as the Foreword to the 2014 Humanoids Inc. edition of Barbarella.