Hergé & The Clear Line:

Part 2

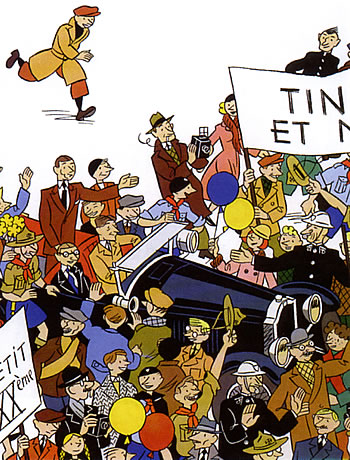

The plucky boy reporter Tintin celebrated his 75th birthday in January 2004 as a Belgian institution popular the world over. While crafting Tintin’s adventures, Hergé, pen name of Georges Remi (1907-1983), had learned from his predecessors and peers, and developed a clarity of drawing, composition and narrative that would later become known as the Clear Line. After World War II, Hergé went on to apply these lessons as the director of his own studios and as the director of the new Tintin Weekly magazine. A whole school of comics grew up around him. By the early 1970s, just when it was in danger of becoming tired and academic, the Clear Line’s discipline and innocence underwent a whole range of rejuvenating interpretations in the Dutch underground comix and French-language bandes dessinées of the ‘70s. Today, over twenty years after his death, Hergé‘s influence on comic artists shows no sign of fading.

THE BRUSSELS SCHOOL

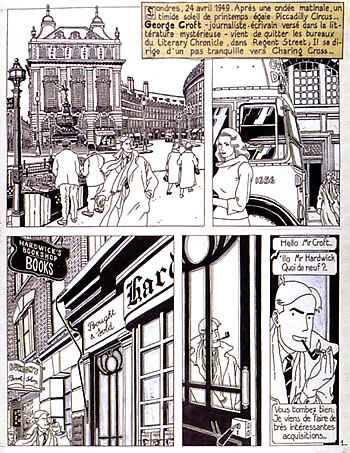

Almost from the start - as far back as the ‘30s - Hergé‘s Tintin had its imitators, mostly charming but unsophisticated copies. But it was during the heyday of Tintin Weekly, Kuifje (small quiff) in Flemish, that Hergé oversaw, and as "art director" often guided, a group of contributors to follow his principles. In 1951 they became known as L’École d’Hergé (the Hergé School), and decades later the Brussels School. Among its leading members must be Hergé‘s former collaborator Edgar P. Jacobs, whose solo science fiction/thriller series Blake & Mortimer is a Belgian classic, "by Jove!" Captain Francis Blake and Professor Philip Mortimer are more English than the English as they solve baffling mysteries, from London’s fog-shrouded docks to the pyramids of Cairo. As thoroughly researched as Tintin, Jacobs’ albums have little time for humour and the texts are overwritten, but their melodrama and imagination have kept them hugely popular. So much so that, unlike Tintin, further adventures have begun to be produced since Jacob’s death, illustrated in strict retro fashion by Ted Benoît and André Juillard (see below).

Another three significant Brussels School members served their time on staff at the Studios Hergé. Former animator Bob de Moor (1925 - 1992) became Hergé‘s right-hand man when he joined the Studios and would in the end often sketch the poses and expressions of the characters for which Hergé himself posed. They did hundreds of these, from the simplest movement of a hand answering a phone to Captain Haddock as a young sailor or Professor Calculus at the age of six. For other references, specifically decor, de Moor used the furniture, lamps, doorknobs, in fact practically everything in the modern Studios Hergé. His own strips for Tintin Weekly included the zany police inspector Mr. Barelli, the swashbuckling Cori the Ship’s Boy, and gag strips with Calculus’ sort-of "cousin", called Balthazar.

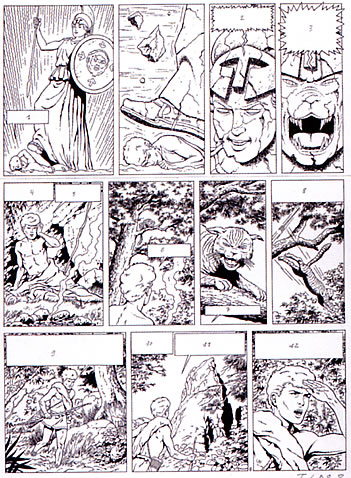

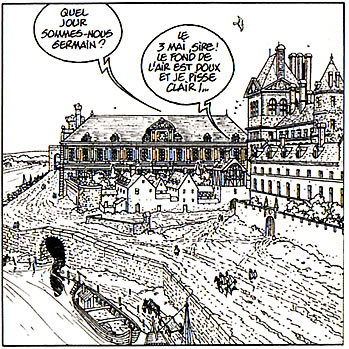

Frenchman Jacques Martin (b. 1921) graduated to Tintin Weekly in 1948 from rival Belgian weekly Bravo, but not without some stern critiques from Hergé. Still, Martin’s experience in engineering, airplane and theater design came in handy for his assistance on backgrounds and details at the Studios Hergé, where he was also involved in the Tintin stories and worked until 1972. His most famous character is Alix, a young Gallic chieftain in the year 53 BC who is adopted by a Roman but is torn by conflicting loyalties. His saga bs over twenty studiously researched, classically drawn albums that Martin wrote untill 2006. Like Martin, Roger Leloup (b. 1933) had grown up on Tintin and was Martin’s assistant before entering the Studios Hergé in 1953, where he became one of Hergé‘s leading colourists and technical draftsmen. He left in 1969 to create his Japanese space heroine Yoko Tsuno, for the rival Belgian comic weekly Spirou, which he has continued ever since.

Two other notable artists on Tintin received weekly guidance from Hergé. Willy Vandersteen (1913-1990), who became a close buddy of Bob de Moor, the other talented Fleming, had already become successful since 1945 with his Flemish brother-and-sister act, Suske en Wiske (Bob et Bobette in French), full of improbable magic, time travel and fantasy. Humorous and quite different from Tintin, with its feet on the ground. Despite his reputation, when Vandersteen was commissioned to create special new stories for Tintin Weekly, he heeded Hergé‘s severe misgivings and put extra effort into his drawings to make them tidier and less "vulgar". His moniker, the "Bruegel of comics", indicates his delightful Flemish bluntness, which Hergé sought to sanitise from the ‘40s on. Vandersteen ran his own studio like a production factory, constantly pumping out fresh adventures in daily newspaper strips (syndicated also in the Netherlands and Germany), collected in soft-cover albums today totaling over 300 titles. A far cry from the snail’s pace at the studios Hergé. On the other hand, Hergé‘s guidance to the young and troubled artist Paul Cuvelier (1923-1978) took the form of long, intimate conversations to persuade him to pursue and persist with his realistic comics, when painting attracted him more. Over time Cuvelier drew eight exotic tales of his beautiful boy hero Corentin.

For all the qualities of these and other artists on Tintin Weekly, molded directly or indirectly from his lead, Hergé had misgivings at the time about the sameness of the periodical’s look, as he revealed in a telling passage from 1952 excerpted in Benoît Peeters’ 2002 biography:

"I recognise that I may have seemed to encourage them in this direction, by insisting always on the clarity, neatness, readability of the drawings. But we are now reaching a uniform style which may end up creating monotony and risks tiring certain readers (and not appealing to those who could become readers). To my mind, only an artist who finds his own genre, who uses a new language adapted to the times, who finds gripping and personal means of expression, can really stand a chance."

The evidence was there. If the Clear Line becomes too rigid a discipline, it might stifle individualism and produce sameness. But it would not be long before the Clear Line changed with the times.

THE DUTCH UNDERGROUND

The label Klare Lijn (Clear Line), Dutch wordplay with a Flemish slant, was presented to Hergé only weeks before it appeared in print in February 1977. (Hergé disliked the "art only" aspect of it immediately and started arguing the importance of the hierarchy in his work: in his mind scripting, framing, montage and composition came before drawing style). In Belgium’s neighbouring country, the Netherlands, an exhibition on Tintin, Kuifje In Rotterdam, was organised by experts Har Brok and Ernst Pommerel, assisted by underground comic artist Joost Swarte (b. 1947). Using the Hergé-like pen name Esjé (from S.J., his reversed initials), Swarte illustrated and designed the covers for four catalogue booklets to resemble classic Tintin albums. One of these surveyed the artists who had been inspired after the war and after the early ‘70s by Hergé. This booklet Swarte titled De Klare Lijn, meaning a perfectly straight line traced with garden string.

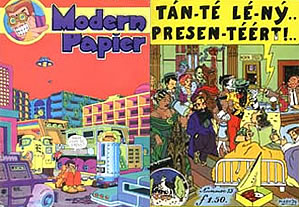

The modern European revival of the Clear Line had blossomed initially in the permissive, drug-friendly, and English-speaking Netherlands, where the uncensored, iconoclastic American underground comix of the ‘60s, headed by Robert Crumb, were most easily imported and imitated. The sober, moralistic, well-behaved "establishment" of the Brussels School could not be more different from these underground comix. The underground cartoonists’ example stirred a new generation of rebel Dutch comic creators, who had grown up absorbing the Clear Line, to convert and subvert its approach to their own ends in such homegrown underground comix and papers as De Andere Krant, Modern Papier, and the longest running title Tante Leny Presenteert (Aunt Leny Presents, named after co-editor Evert Geradts’ then wife).

Under the signature Esmé (S.M., his reversed initials), Mark Smeets (1942-1999) set the ball rolling in the late ‘60s and the early ‘70s with his quirky, almost trembling period sketches, covers, and illustrations echoing Herriman’s Krazy Kat and reviving Hergé‘s older, freer style of the early ‘40s. They prompted Swarte to look again at his childhood Kuifjes (Tintins) through adult eyes. Trained as an industrial designer, he had dropped out and started his own magazine, Modern Papier. He talked about rediscovering Hergé in his first English-language interview with me in Escape Magazine #3 in 1983:

"In the beginning I drew in Hergé‘s style to study how he did it and I found that it suited me well. I could draw all the details, architecture and design things. You can make a major story about the people in the strip and then underneath that you can have a minor story about a little dog or a chair and it can all be seen very clearly. At first it was a study, then I couldn’t think of doing anything else."

Crumb and other American underground artists had reclaimed their comics forebears into their strips; now Swarte and others were doing the same for their own heritage, by mixing Hergé‘s innocent-looking storytelling and drawing with a healthy dose of perverse irony and irreverence. It’s perfectly summed up by the neat little mounds of doggie poop on Swarte’s sidewalks, waiting to be trodden on. He also drew on the sophisticated line cartoonists of the past, among them Ralph Barton, Rea Irvin and Gluyas Williams in The New Yorker, and Nicolas Bentley, Pont and Fougasse in London’s Punch.

Swarte’s kooky cast features hapless rocker Jopo de Pojo, who sports Tintin’s plus fours trousers and combs his hair into a striped quiff, and the double act, mad inventor Anton Makassar and his lumpen assistant Van Genderen. Expatriate fellow Dutchman and cartoonist Willem, alias Bernard Holtrop (b. 1941), had moved to Paris and in 1973 began writing stories for Swarte in Charlie magazine, which acted as a doorway to the past for France’s Ligne Claire. Swarte explained to me, "After this people jumped onto [the Clear Line] too seriously. You can tell something from the line, the way you draw, but if you are not going into the mentality of the different artists, then you have only been talking about half of it." One of the wonders of the Clear Line is how varied those mentalities became, as if each creator was answering Hergé‘s call in 1952 for "an artist who finds his own genre, who uses a new language adapted to the times, who finds gripping and personal means of expression." As for Swarte, he distinguishes his approach form Hergé‘s succinctly: "Hergé tries to take the reader to the real world; I take the reader into my world."

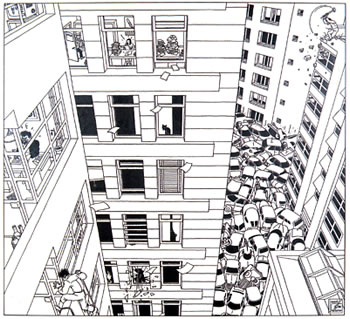

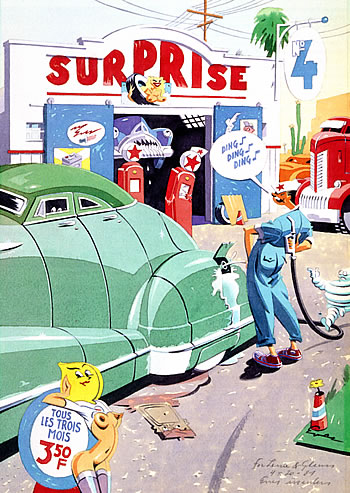

Among others in the 1977 booklet De Klare Lijn, and showcased by Tante Leny Presenteert, were Harry Buckinx (1944-1995), for a while heavily inspired by Tintin in his seedy Titula & Titul, and notably the Belgian Ever Meulen (real name Eddy Vermeulen, b. 1946). Meulen came to the Dutch underground via his art academy studies and his passions for ‘60s Pop Art, American ‘50s music, cars, design and ‘30s Art Deco. The shock of Crumb and the West Coast counterculture led him to rediscover the comics of his youth and pay homage to them in his own. "I was not heavily influenced by Hergé, except through Jacobs. When I was eight, Blake & Mortimer were my favourite albums." Comics had been only one of his influences and would become only one facet of his career in magazine illustration and poster and record sleeve design. Like Swarte, Meulen’s ever-changing style makes multiple references to an array of visual culture, from Saul Steinberg to Giorgio de Chirico, but he takes the sources to an extreme in his fractured, angular compositions, and disrupts and reinvents the Clear Line by setting trompe l’oeil puzzles of perspectives and perception. Again it was Willem as editor of Surprise in Paris in 1976 who introduced Meulen to France, heralding his influence on comic creators across Europe (Serge Clerc in France, Daniel Torres and Max in Spain, Hanco Kolk in the Netherlands, Hendrik Dorgathen in Germany, for starters).

It was only after more than a decade of humorous and erotic strips in Hitweek/Aloha and other Dutch magazines that Theo van den Boogaard (b. 1948) radically switched to the Klare Lijn in 1976. He had grown up preferring the albums of Willy Vandersteen, his first stylistic model, and blended this with lessons from Hergé to draw the Dutch TV comedy character Sjef van Oekel, a pompous, volatile Jack Benny-like time bomb in specs, tuxedo and bow tie, oblivious to the embarrassments he causes. His colour antics written by Wim T. Schippers appeared weekly in Nieuwe Revue and traveled as Léon van Oukel/Léon la Terreur to France. "Hergé‘s influence on me concerned composition: the construction around a perfect center of gravity. And the treatment of colour." Frozen moments of outrageous chaos have never been delineated so exquisitely.

LA LIGNE CLAIRE: THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

Especially with its conversion to colour, the Tintin series had become as big a success in France as in its birthplace, Belgium, and helped stimulate the French market for hardback albums of comics, or bandes dessinées, aimed mainly at children. The ‘60s changed that. Championed by intellectuals, elevated to a new ‘Ninth’ Art, exhibited in the Palais du Louvre, the bandes dessinées medium - caught in the May 1968 cultural quake - bloomed into more sophisticated subjects and styles that hooked adult readers. Out of this came a tide of Francophone artists working in the Ligne Claire, of whom the following are a handful of the most distinctive.

Nothing better demonstrates the French evolution towards the Clear Line than the book of that name, Vers La Ligne Claire, a 1980 collection of short works from the years 1975 to 1980 by Ted Benoît (b. 1947). It charts his journey from his first pieces inspired by Crumb and Moebius, through his experiments influenced by the line graphics derived from photographs by Loulou Picasso (from the French group Bazooka Gang), ending via Smeets and Swarte with their return to Hergé. Benoît’s detective is a Clark Gable look-alike by the fruity name of Ray Banana, a play also on the Ray-Ban shades he wears and his quiff, "banane" in French slang. He stars in the 100 page Berceuse Electrique (Electric Lullaby) packed with film noir references, and Cité Lumière (City Of Light), which was coloured by the Studios Hergé. Benoît also created zany Bingo Bongo pages for Métal Hurlant and came full circle in 1996 when he drew the first of the revivals of Blake & Mortimer.

In contrast, Jean-Claude Floc’h (b. 1953) was influenced by the Ligne Claire from the moment he started Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks, serialised in Pilote in 1977. This was the first of three murder mysteries he elegantly illustrated, cases solved by the detective duo, writers and amateur sleuths Francis Albany and Olivia Sturgess. Rich in literary and historical references, this "English Trilogy" is written by fellow Anglophile François Rivière (b. 1949) in the best Agatha Christie and Hitchcock traditions. Of the qualities in Hergé‘s albums, Floc’h has explained that the adventure aspect no longer appeals to him. "What attracts me are the static elements. The album I prefer is The Castafiore Emerald, it’s everything that doesn’t move. I adore a closed set. I’d like to be able to impress the reader with a story that takes place around a cup of tea." With his tweeds, pipe, and golfing club, Floc’h still lives the part and has gone on to success in advertising and illustration, recently for The New Yorker. Jean-Louis Floch, without the apostrophe (b. 1951), followed his younger brother’s lead and has drawn both light children’s adventures and darker adult satires, notably by writer Jean-Luc Fromental.

Before his tragic death in a car crash aged only 33, Frenchman Yves Chaland (1957-1990) forged his own iconoclastic fusion of the Franco-Belgian masters from both Tintin and the more free-spirited Spirou/Robbedoes. These artists, worthy subjects of a future article, became known as the Marcinelle School and were later christened, again by Swarte, as Le Style Atome, after the Cold War atomic era and Brussels’ futuristic Atomium attraction from 1958. Referential if not always reverential, Chaland steeped himself in Belgium’s postwar traditions. Out of them he crafted five ripping yarns of his plucky adventurer Freddy Lombard and, in his most personal masterwork, some 70 seemingly slight vignettes about life’s lessons as taught by a fiercely independent street kid, Le Jeune Albert (The Young Albert), cruel and contradictory as only children can be. Chaland’s work shone a path that many would follow.

In the historical genre popularised by Jacques Martin, André Juillard (b. 1948) stands out as one of the most adept for his sensitive linework and thorough documentation. His series included three volumes of Arno about a Venetian musician who saves Napoleon Bonaparte’s life, a collaboration with Jacques Martin. He has also illustrated one of the Blake & Mortimer revivals and, in a completely different register, written and drawn The Blue Notebook, a bittersweet psychological love triangle set in present-day Paris.

Much more space would be needed for profiles of the dozens of other French-language disciples of the Ligne Claire, but from France, Belgium and Switzerland it crossed borders into Spain and Italy and encouraged creators there too. Trained in architecture, Daniel Torres (b. 1958) is the most prominent graduate of the bish Linea Clara grouped around the escapist magazine Cairo from 1981. First noticed in Opium, Torres imitated the shoulder pads and tail fins of Meulen and Swarte in a deliriously silly retro-future romp. He then invented his matinee idol Rocco Vargas, retired space pilot, now living a quiet life as Armando Mistral, science fiction writer and nightclub owner, but the stars soon beckon him back. Torres’ early baroque flourishes matured, as he adopted the brush, towards the lush control of Chaland, while he was also inspired by bish pioneers of La Linea Clara such as Benejam, Opisso and Josep Coll. As a true maestro of the Clear Line from Italy, Vittorio Giardino (b. 1946), a former electronics engineer, broke into the fumetti business in 1979 with his private detective Sam Pezzo, ‘30s spy Max Friedman, and erotic dreamer Little Ego, in tribute to Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo In Slumberland. More recently he has undertaken his most touching series, A Jew in Communist Prague, convincingly capturing real life behind the Iron Curtain for young, fatherless Jonas Fink.

The Clear Line has given rise to all of these lines, so very different in their style and mentalities, as Hergé had called for back in 1952. And what of the Clear Line today? In present-day Belgium and France, some now consider it out of fashion and favour. As Thierry Smolderen commented on the Comix Scholars list: "Since the early ‘90s the Ligne Claire is nearly never mentioned anymore, and Hergé‘s ubiquity is a thing of the past… the 1970s and ‘80s have over-exploited the Ligne Claire stylistically - there was a time when every advertisement in France and Belgium was drawn is this style." True there was overkill and something of a backlash, but the Clear Line is more than a surface style or nod to nostalgia. To my mind, its whole dynamic is still very much alive in current bandes dessinées. I see it being applied on the one hand to elegant adaptations of Agatha Christie or Marcel Proust, while also being reinvigorated by the lurid precision of Killoffer, the teeming inventions of Lewis Trondheim, or the fragile freshness of Stanislas, appropriately the illustrator of a biography of Hergé in bande dessinée form, translated in Drawn & Quarterly Vol 4.

The Clear Line can be seen as a living, growing tree that spreads its roots down deep into the soil of visual history, while its boughs continue to sprout fresh branches and grow in their own directions. It has been disseminated to America via the Tintin albums and since the ‘70s through translations in Heavy Metal, Raw and others, to the point where the Clear Line’s latest, greenest sproutings could well be Jason Lutes’ Weimar re-creation in Berlin, Seth‘s reflections on the artist’s struggle in It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken, and Chris Ware‘s unflinching candour. Couldn’t his Jimmy Corrigan be Tintin‘s distant chubby American cousin?

The Clear Line has come a long way through the last century. Today, we can still return to Hergé‘s thousands of lines, each the product of thought, expression, effort and inspiration, which he wove together into the 23 Tintin albums. The lines of Hergé‘s work and life are his lasting legacy.

I am deeply indebted to Charles Dierick, Thierry Groensteen, Bruno Lecigne, Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier, Benoît Peeters, François Rivière, Numa Sadoul, Thierry Smolderen and Pierre Sterckx, the well known Belgian and French Tintinologists, for their researches and insights. A special thank you to Dutch researcher and biographer Huib van Opstal for his wealth of new insights and material.

Posted: May 11, 2008The original (copiously illustrated) version of this article appeared in the summer of 2003 in Comic Art Magazine #3

, published in the US by Todd Hignite.