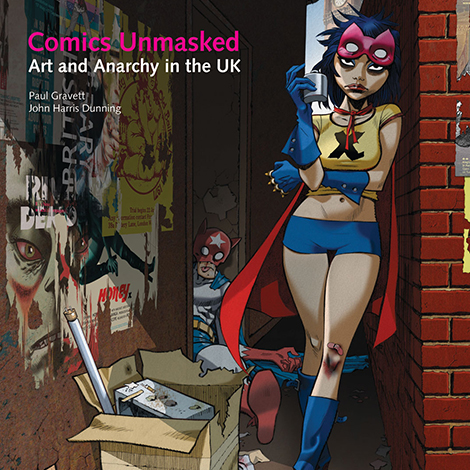

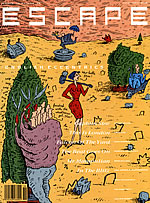

Escape Magazine:

The Great Escape Twenty Years On

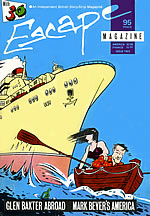

Can it really have begun only twenty years ago? It’s hard to believe that 2003 marked the 20th anniversary of the first issue of Escape, the British comics magazine which Peter Stanbury and I co-edited nineteen issues of until Autumn 1989. For six years Escape helped to promote an evolving bunch of distinctive British creators, many of whom were quickly picked up by other comics publishers and by the UK music press, newspapers, magazines and galleries. Now is a good time to look back at how we came together and what some of the singular ‘Escape Artists’ have achieved and are achieving still.

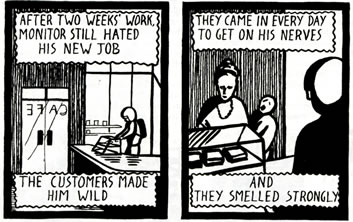

Nothing to do with Houdini, ‘Escape Artists’ was no more than a name, because they obviously never ‘belonged’ to us or to anyone, and they never saw themselves as a unified group. What they did all have in common, though, were their art school backgrounds, by and large, their strongly individual approaches that ignored genre and formula, and their openness to all kinds of influences from within comics and beyond. Cumulatively, their work appears as idiosyncratic and refreshing as ever and continues to motivate successive generations of cartoonists on both sides of the Atlantic.

Today, two decades after the birth of Escape, it seems so much easier and more natural to think and network globally, to look at the bigger picture. With e-mail we can make connections in the blink of a synapse. We can let the world and its websites flood into our home computer screens. In the American comics landscape, specialist stores, as well as many bookstores and libraries, fill their shelves with squarebound graphic novels that can earn literary awards and top the charts as Hollywood movies. Alternatively, you can bypass all the middlemen and deliver your paperless comics online direct to readers anywhere. Of course, physical gatherings of the clans, like the Angouleme Festival in France or ICAF/SPX in Washington, are still important and now truly international, bringing people together from all over the world, but the contacts they make there in the flesh can now go on to develop virtually.

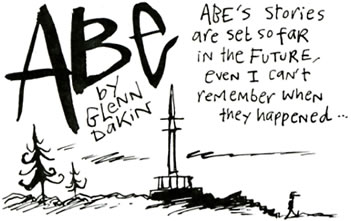

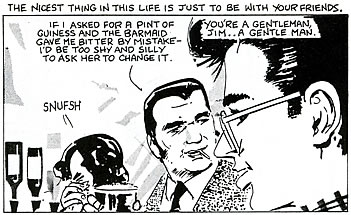

All this feels like living in some whiz-bang, sci-fi future out of one of Glenn Dakin’s loopier Abe strips, when compared to just twenty years ago, pre-internet, pre-manga (Barefoot Gen had barely begun), pre-Maus (only the first chapters in Raw), pre-the full-scale British Invasion of America comic books (sparked by Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing the next year). Back then, it was more low tech, haphazard and human, in a way. For instance, in Britain the comics community would write each other letters, usually by hand, and might meet up in each other’s homes, down the pub or at Comic Marts or the annual Conventions. And through the modern miracle of xerography almost anyone could photocopy their own comic, sometimes as few as ten or twenty copies, and try selling them in shops, at marts and, if you got it reviewed in one of the few fanzines, through the post.

Around September 1982, Peter Stanbury and I moved into our first apartment together, where we decided that it would be fun to run a comic magazine. It was Peter who hit on the perfect name - Escape - not so much for ‘escapism’, more from the idea of breaking out from the stifling conformity of the comics mainstream. At the time, Peter had risen through the ranks at Harpers & Queen magazine, a high-society, high-fashion women’s glossy, and he knew everything about print design and production. I was less than a year into my first proper paid job in comics at the unfortunately named pssst! magazine. This was the misguided dream of a delightfully wacky and wealthy French couple, Serge and Henriette Boissevain, who were convinced that a British attempt at the sort of luxurious ‘adult’ bande dessinée magazine that sold in France would make a fortune here; instead, it nearly lost them theirs.

I had started at pssst! late in 1981 as their promotions man, touring England in the middle of winter with a beefy driver Mick and a punky assistant Nick on a double-decker London bus. Outside, its side windows were covered and painted with wild cartoon graphics, while inside, the seats downstairs had been removed to make a shop, and the seats upstairs were kept to form a cinema screening a back-projected, sound-and-light comics slide show, for adults only. On the road one of my duties was to seek out new artists and we found more than we could imagine. One discovery when we hit Manchester’s art college was curly-haired student Glenn Dakin, whose devilish cartooning on Temptation quickly made it into pssst! magazine.

In the end, after being hounded out of town by irate council officials and scraping ice off the inside of the windows (thankfully we never had to sleep on the bus), it was a relief to be taken off the road for good. I got an ideal job back at the offices as Traffic Manager, co-ordinating artwork and interviewing potential contributors. There was a buzz to opening each day’s submissions and presenting them to the weekly editorial meetings. I got to see loads of art and artists and I learnt a lot about magazines, both what to do and what not. Put together by committee, pssst! was a camel of a magazine, which was forced to close after ten ssues.

Escape partly grew out the frustrations I felt at having no say about pssst! magazine’s contents and seeing them reject such great material, including Eddie Campbell’s life-affirming, autobiographical Alec. I had landed the job at pssst! in the first place, because its main editor Mal Burns knew about my contacts within the UK small press scene. Earlier in 1981 I had started Fast Fiction, a stall, ‘Info Sheet’ and mail order service, based at the bi-monthly Saturday Comic Marts at Westminster Hall, London and open to everyone. By providing encouragement, feedback and a regular meeting-place, Fast Fiction brought together self-publishers from across the country into an ever-changing, do-it-yourself revolution, one source to find many of the Escape Artists to come.

Once I started working at pssst!, comic artists Phil Elliott and Ian Wieczorek, local Essex friends since my school days, had taken on Fast Fiction and soon wanted to publish their work in a Fast Fiction magazine. The first artist to join them had to be Eddie Campbell, another Essex boy down in nearby Southend-on-Sea, his ‘Letratone Impressionism’ and seaside slice-of-life total revelations when we discovered his limited-circulation ‘apa-zine’ Flick. I think it’s safe for me to confess now that on Saturday mornings, I’d moonlight with the three of them in the pssst! darkroom and reduce their pages for free on the fancy PMT (photo-mechanical transfer) machine for printing. What’s more, several artists in the first Escape had either debuted, or were about to, in the pages of pssst!, not only Glenn Dakin, but also Paul Bignell, Rian Hughes, Paul Johnson and Shaky Kane. In a real sense, Fast Fiction magazine, and Escape that followed, owed much of their beginnings to pssst! magazine.

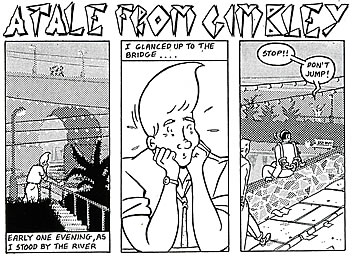

For our models for Escape, Peter and I were looking as much to Europe as to America. There is no denying the fundamental example set by spiegelman and Mouly’s Raw, bridging the American underground with its European counterparts. To give the Escape strips, largely by unknowns, some context and help them sell, we wanted to interweave them with editorial and ‘Snacks with the Stars’ interviews (Clerc, Beyer, Swarte, Mariscal, Briggs, Burns, Moore, etc), a recipe applied by anthologies like Métal Hurlant, Charlie Mensuel, A Suivre and PLG in France and Seventies’ American forerunners Arcade, Heavy Metal and Cascade Comix Monthly. We settled for the first seven issues of Escape on a digest or ‘A5’ size, cheaper to print, handy for mailing and what most small pressers were used to and suited to. Covers were wraparound, laboriously hand-separated by Peter until full process color arrived from issue six. With nobody getting paid except the printers, Peter and I put in a couple of hundred pounds each to produce the first issue and Phil Elliott drew the cover and lead strip starring his quiffed teenage Tintin, Gimbley. We were off.

Considering its modest quality, Escape #1 generated a disproportionate amount of media interest, especially in the music and style press, and we found subscribers, retailers, distributors and from the second number much-need advertisers. We also found more artists, through the Fast Fiction channels, and by other means. Myra Hancock was selling her spiky, spirited Myra Magazines on Camden Market dressed like a punk match-girl or cinema usherette, while Chris Long had just got back from Italy where he’d been contributing trendy fumetti to Frigidaire. Later, there was the thrill ‘discovering’ Carol Swain drawing her first ever magical comic at an Escape workshop, and Warren Pleece, exhibiting his mean and moody noir strips at a degree show.

Rightly or wrongly, Escape was a living thing in restless evolution, in format and contents. No issue was ever exactly like another. Inevitably, not every contributor liked everything in every issue. While we had some regulars for a time, this turnover was partly due to our finding the next ‘young guns’ to promote, making some artists feel eclipsed or no longer ‘flavor of the month’. It was also partly caused by artists moving to other projects and publishers, for example Knockabout, Fox Comics, Splat!, Ark, Heartbreak Hotel, Fantagraphics’ Honk! and the black and white, boom and bust of Harrier’s genre comic books. It was only human nature for us to be a bit nervous and reactive about this perceived threat to Escape‘s identity. Knockabout could pay their contributors, so that helped persuade us that we should too. Escape had always been run in an informal, gentlemen’s agreement manner, but when Honk! insisted on tying cartoonists strips down in contracts, we felt obliged to try also, to a mixed response. Peter and I lived and breathed Escape, few people saw how much thought and work we poured into it, and in the end we came to realize that the most important element that defined Escape was our editorial vision.

I think there is a natural life cycle to comics anthologies. Like rock bands or marriages, they can’t always last or stay the same. There is a tendency to start off with a core group and add to that, often expanding the page count to bursting point accommodate them all. A total re-think often follows and a shift in format, the addition of colour, a switch from complete stories to a serial or two perhaps. In Escape‘s case, we kept on adding new artists, culminating in our bulging ‘Bumper’ issue seven.

Next came the most controversial stage, a change in logos to Peter’s extra-pronged, eccentric typeface and expansion to American magazine size, reflecting a greater confidence in the contributors’ artwork, enabling us to translate work from Europe (Tardi, Munoz & Sampayo, Mattotti, Swarte, Götting etc.) and putting us more prominently on newsstand and comic shop racks. With issue ten, after protracted negotiations, we were published squarebound by Titan Books. Try as they might, we resisted any attempts to dictate the contents, but it was occasionally a bumpy ride. Titan was never behind our goal of getting Escape distributed more widely into newsagents across Britain. After two years and ten issues, we parted ways with our last issue, nineteen. Peter and I showed around a third incarnation of Escape, a gorgeous monthly, bigger still with colour and imported serials, which impressed several non-comics publishers, but not enough to take the plunge. Escape left a void and I’m not the only one who thinks it has never quite been filled by further Brit anthologies, big-time or small press - Crisis, Deadline, Revolver, Xpresso, A1, Inkling, Scenes From The Inside, Blast, Strip.

I’ve asked some of the contributors about their feelings about the Escape days. Eddie Campbell’s emigration to Australia could have meant his being remote if not completely exiled from the US/UK comics industries. Instead, through sheer drive and creativity, he has become a major force in the field and come full circle back to being a self-publisher again, though this time on a much grander scale, thanks his massive From Hell tome written by Alan Moore becoming a movie and an international best-seller. Eddie once commented, in Arkensword #17-18, 1986, "the whole small press movement…[is] the first real upheaval in this country of Comics as a genuine Art - Art being to me a thing which is a lively part of life while commenting on life - as opposed to comics as journalism-cartooning or comics as a collecting-hobby or comics as boys power fantasies."

Eddie has transformed his experiences of Escape and the whole heady period into a unapologetically skewed diary-cum-self-help graphic novel, Alec: How To Be An Artist. I can’t help feeling flattered by his mostly positive portrayals of me as ‘The Man At The Crossroads’, but everybody had their own experiences and perspective, their personal history. With hindsight, I’m more aware of all the expectations which, knowingly or not, Escape helped to raise in many people, not least in Peter and myself, the fallings out and the difficulty of going on with your life. Phil Elliott has written movingly about these ambivalent feelings in two stories drawn by Paul Grist, another light that shone in later Escapes. In Stage Struck, I appear in these stories in a less flattering guise, as ‘Tony’, a flighty band promoter, always positive but always in search of new acts, in a field that becomes ‘all glitz without a conscience’. Phil’s alter ego is a woman singer-songwriter who feels hurt and disappointed. In its coda, In Sight Of…, set a year later, Phil’s songstress seems reconciled, more realistic, less trusting perhaps, yet unable to resist the ‘tantalising enticements’ from publishers. These are sobering, sensitive pieces. I had never thought how dangerous raising hopes could be.

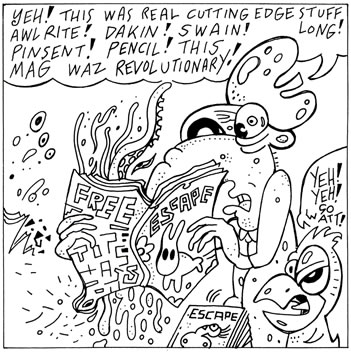

It would be a mistake to pretend that everything went smoothly and everyone got along. Glenn Dakin in The Comics Journal #238, October 2001, explained that Escape "provided a focal point for people. People would meet up and discuss their dreams and ideas and get together as friends or have arguments and fall out and sometimes even if somebody annoys you or if somebody didn’t seem to have respect for your work, that would be enough to fill you with enough anger to go out there and try to prove them wrong." Recently, John Bagnall told me, "To some readers at the time, Escape Artists were sometimes generalized as the school of strips "where nothing happened", but their approaches were actually much more disparate. As for the social scene, there was a loose sense of unity when we would meet up in London, though naturally not everyone got on well or were even huge fans of certain people’s work. I remember on one visit laughing at Mark Robinson’s wry comment that the UK scene was more ‘Vicar’s Tea Party’ than the Haight Ashbury revolution he’d just watched in a TV documentary on Robert Crumb!" I remember another reviewer likened the first issue to a village cricket match.

Nevertheless, after Escape was over, many of the creators whom we helped get wider exposure soon found clients and outlets for their work, from strips in national and local newspapers (Phil Elliott’s The Suttons, Woodrow Phoenix’s Sumo Family, Warren & Gary Pleece’s Seventies Cop) to solo comic books and graphic novels (Carol Swain’s Way Out Strips and Chris Reynolds’ Mauretania graphic novel from Penguin Books). Both Hunt Emerson and Savage Pencil had already clocked up several years in UK underground comix and rock papers, but they were youthful, committed mavericks and we were so lucky to be able to invite them to cut loose in Escape‘s pages. And a pair named Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean, first seen together on the Escape graphic novel Violent Cases, have gone on to do a few odds and ends, together and separately.

To wrap up, I’ll let John Bagnall blow our trumpet for me. "Picking some back issues off the bookshelf, I’m amazed at how many cartoonists were included, how most of the reviews were intelligent and non-fanboy-ish, and how well designed the whole thing was. It hasn’t dated significantly either, probably because the Escape vision was always forward-looking." So let’s take a look at some of the Escape Artists’ recent and upcoming projects. Phil Elliott’s graphic novel written by James Robinson, Illegal Alien, is in the pipeline for re-release, while he’s colouring Paul Grist’s Image debut, the charming British superhero Jack Staff. Glenn Dakin wears so many hats, it’s hard to keep up, but his Abe collection came out last year from Top Shelf and still draws his Robot Crusoe weekly strip for The Sunday Times. Ed Pinsent just published his tenth issue of The Sound Projector, surely one of the most intense and enthused music journals on the planet. Chris Reynolds has a 30-minute live-action Mauretania film out Summer 2003, Hunters Of The Sun. Woodrow Phoenix is in heaven working on his Cartoon Network animated version of Pants Ant, one of the Sugar Buzz cast written by Ian Carney for Slave Labor. Carol Swain returns with her second Fantagraphics graphic novel Food Boy, published in Spring 2003. John Bagnall has his first all-new strip collection out imminently from Kingly Comics, Don’t Tread On My Rosaries, mining his affections for Roman Catholic excesses and Northern English peculiarities. Savage Pencil has illustrated Ken Hollings’ book Destroy All Monsters and Warren Pleece is laying out a new DC Vertigo Pop series for Philip Bond (yet another first promoted in Escape).

This is proof that many of Escape‘s contributors are still very much involved in today’s comics-related culture. Looking forward a little further, the 20th anniversary of Escape is looming. I’ll leave the last word to Mr Campbell who recently wrote to me: "I remember what I liked about your Escape philosophy was that comics were culture and that they were of a particular sort, comics culture, a vision of the world cultivated through the best cartoons. A hip, alert, humorous, informed, aware, international view. We could assume that one who knew all the right comics would not be a political jerk for instance. Nor would he or she be an Art jerk." That sounds like a pretty good philosophy to me.

This is dedicated to my friend through comics, Alan Gaulton (1956-2002), in gratitude for all of his generosity and humour through the years.

Posted: May 7, 2006A revised version of this 2002 article appeared in The Comics Journal Special Edition Vol 3, Winter 2003, accompanied by a portfolio of brand new one-page strips by several Escape Artists.