Emmanuel Guibert:

Memories And Memoirs

As Emmanuel Guibert turns fifty this year, three overriding goals have come to motivate him: “Making people, especially children, laugh, so that I can get back to the source of my love of comics and give kids all that I felt myself when reading my favourites. Then, trying to capture life through reportage. And finally, collaborating with friends I get along with well but who are also very different from me, so they take me where I’d never go on my own.” The results are a vibrant diversity of projects and approaches from a natural collaborator, whether he is working as writer or artist with his fellow French comics creators, or with his close friends, transforming their memories into unforgettable graphic memoirs.

Born in Paris, Guibert enjoyed a blissful childhood and supportive parents, who nurtured his love of drawing. “One of the first words I spoke was ‘pencil’.” He grew up in the south-east of France in the Basses-Alpes, formerly part of Provence. “A lot of what I am doing now comes from the enthusiasm that filled my childhood, the idea that life is something to celebrate.” By the time he entered art school in Paris, he was already working as an illustrator and storyboard artist, so he decided to leave after six months. Taken under the wing of Tanino Liberatore, co-creator of Ranxerox, the virtuoso Italian artist introduced Guibert to his publishers, who commissioned him to develop a plot about the rise of Fascism in Thirties Germany. So laboriously researched and hyper-realistically painted, Guibert’s 48-page graphic novel debut Brune took him six solitary, draining years to complete by 1992.

Where had his childhood passion for comics and drawing gone? Something had to change. Guibert set himself the daily task of making a fast observational drawing, to get to the essential. “I felt my drawing become more free, open up, move more easily into unfamiliar territory.” He also forced himself to experiment with unusual techniques, discovering processes he has used later in his books. “It’s my chronic dissatisfaction at being unable to reach a level of total confidence - which would actually be the height of boredom - that pushes me to keep on trying to find solutions.”

The other big change was joining a studio of his peers, who became his mates and part of ‘La Nouvelle Bande Dessinée’, the new generation who re-energised French comics. In 1994 he met David B. and through him was introduced into the Atelier Nawak, not far from the Centre Pompidou, and later the Atelier des Vosges, joining brilliant rising stars like Joann Sfar, Lewis Trondheim and Christophe Blain. The initial idea was simply a shared workplace but these studios soon became like a classroom without a teacher, for learning from and inevitably working with each other.

Guibert’s collaborations included children’s comedies about Sardine, a feisty pirate girl in space created by Joann Sfar, who drew over four hundred pages of them in BDLire monthly before Guibert took over the art as well. The pair swapped roles for other collaborations, each one a different process. On The Professor’s Daughter (above), a Victorian romantic burlesque between the leading lady and a resurrected British Museum mummy, Guibert experimented with washes and was closely involved in the writing, suggesting changes, scripting pages, working side-by-side with Sfar in the studio. First Second have translated this charmer along with six paperbacks of Sardine.

In contrast, on their three episodes, so far, of Les olives noires (‘The Black Olives’) set in Judea in Biblical times, Guibert left Sfar’s texts untouched and switched to a crisper brush technique. Guibert as writer also teamed up with cartoonist Marc Boutavant on the funny and tender Ariol, tales of your average everyday schoolkid donkey, secretly in love with Petula, the prettiest calf in the class. These are available in English from Papercutz and have been animated for television (see below).

Guibert and company were making bande dessinée albums that were a world away from the precious, time-consuming, over-rendered tradition, one year or more in the making. Theirs were refreshing comics of populist entertainment, brimming with wit and panache and produced at a pace. Luckily these prolific creators had France’s rapidly expanding market to supply. As Sfar urged Guibert, “Think of this as like making a B-movie. You can make books where you put in all you can, your whole life, but you can’t spend 107 years on each one.” Guibert heeded this advice; in 2002 alone he released no less than eight new titles.

Becoming part of this community also connected Guibert to the artist-run collective publishers L’Association, rebels against standardisation and champions of creative freedom. It was for their anthology Lapin that he started making a series of biographical vignettes. In 1994, while on holiday on a small island off the French Atlantic coast, Guibert met the American ex-G.I. Alan Ingram Cope, aged 69. Though separated by nearly forty years, Guibert struck up an intense friendship and spontaneous collaboration with this vivid raconteur, recording hours of his candid stories in his distinct foreign French. Over the next five years, Cope quickly grew to trust Guibert’s visualisations, leaving the artist free to picture the veteran’s life from tapes, letters, phone calls, family photos and the sketches he made, of Alan speaking and his surroundings. Occasionally Alan made drawings himself: “He’d drew me a little drawing if I asked him to specify something, like how his mess kit looked or how he held his machine gun.”

The forty chapters and over 300 pages compiled into Alan’s War offer no gung-ho glories of World War Two combat across Europe but pinpoint incidents of banality, incompetence, humour and horror, and above all Cope’s quest for meaning. After contemplating the priesthood, his growing disenchantment with religion and shallow consumerism led to Cope quitting America in 1948, never to return. Late in life, he realised, “I hadn’t lived the life of myself. I had lived the life of the person others had wanted me to be… And that person had never existed.” Using an astonishingly skilful water-drawing with ink, Guibert puts this personal history into sepia, making the panels look like faded archival documents, with a grainy look evoking the wartime photographs of Robert Capa.

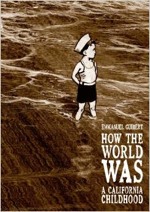

After his friend’s death in 1999, Guibert found a way to reconnect to Cope by visiting friends and locations in America and Germany and through a photo album he left to him, reproduced at the back of the book. Committed to completing his visual chronicle, Guibert turned to Cope’s account of his Californian childhood during the great depression, “probably the most intimate and beautiful part of what he confided to me.” The first part is published in August by First Second as How The Word Was, which Guibert launches at The British Library in London, drawing live at the free Comica Comiket fair on Saturday August 16th, and in a Comica Conversation on Sunday, August 17th (booking details for tickets to follow).

The book opens with flat-coloured vistas of present-day Los Angeles, cars speeding along freeways, in stark contrast to Cope’s recollections of the forgotten city, before the smog and skyscrapers, when “the air smelled like lemons” and oaks and cedars lined the roads (you can read an extract online here). “Life was complete different then.” A boy could find wonder seeing the first planes and his first film in colour, making pepper-tree swings that turn clothes and hands black, and running alongside a steam train, huge and hissing like a black dragon.

As his family move house fourteen times, Cope shares small but telling moments, as well as some very private secrets and tragedies, one in particular that was too big for him to cry about. As Cope confides, “I’m diving down deep to tell you this story, far beneath conscious memory.” Such was the meeting of minds between these two men, that in Guibert’s view, “In retelling Alan’s stories, I don’t feel I am serving any other story than my own. At the same time, it gives me that freedom to change one word into another. Whether he says it or I say it, it’s all become the same.”

In the late Nineties, Guibert undertook a testament to another life, that of French photojournalist Didier Lefèvre (1957-2007), a neighbour and passing acquaintance, always returning from one Doctors Without Borders mission and heading off on another. Guibert felt frustrated not knowing him better. “I thought I’m passing beside a friendship without really living it.” So he asked the photographer to choose one mission and take four hours to tell it to him in all its details. Lefèvre brought him box after box of contact sheets, like panels of a comic, to narrate a gruelling 1986 mission to Afghanistan to bring health care to those in remote regions, on either side of the conflict. “It was like a still movie, that was full of life, thanks to this combination of his words like a voice off and the photos I was looking at.”

Of these 4,000 photos, almost all were unpublished. Feeling this was an injustice, Guibert resolved to record Lefèvre’s story so it could reach the public by making a book together. This became three volumes of The Photographer, compiled into one in English by First Second. With designer and colourist Frédéric Lemercier, Guibert integrated the black-and-white photos, intact, into the page layouts and brought them to life by juxtaposing Lefèvre’s narrative captions and Guibert’s connecting drawings of incidents which the camera had not recorded. The process helps the reader to understand what is happening in each shot, and what happened before and after.

In one of the doctors’ house-calls to a girl paralysed after a bombing, the room was too dark to take pictures. So Guibert draws the scene in silhouettes, lit by the examining doctor’s torch on his head, as he spots a tiny hole in her back. It was made by a piece of shrapnel “no bigger than a grain of rice” and she will never walk again. Lefèvre breaks down, unable to take more photos, but is jolted out of this by the mission’s leader who has just videotaped a child’s death. She tells him, “The mother said to me, ‘Film it, Jamila. People have to know’.” Thanks to this innovative collaboration between Guibert and Lefèvre, more people can know about this tragedy through their timely, deeply humane documentary comics.

Guibert may omit himself from his graphic biographies, but his presence is always felt on the page, the silent other half of the conversation, the listener, observer and translator of his friends’ lives. It’s a way of preserving and prolonging these friendships and enabling us, too, to befriend these remarkable individuals.

Photograph of Emmanuel Guibert by Stanslav Soukup.