Dylan Horrocks:

All Pens Are Magic

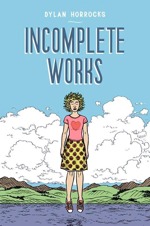

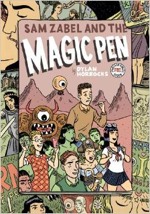

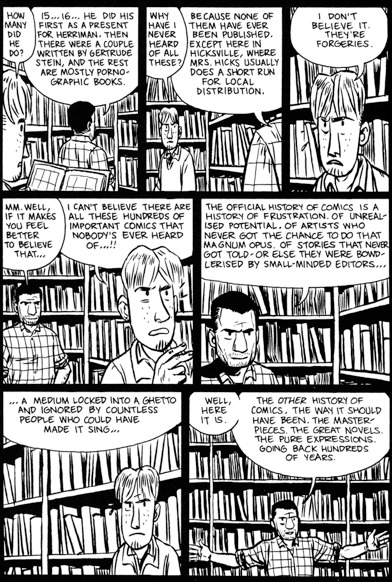

In his solo debut graphic novel Hicksville (1998), Dylan Horrocks envisaged a modest, perhaps unattainable utopia for his chosen medium in the eponymous remote coastal town in his native New Zealand, whose every citizen appreciates the wonders of comics. Hicksville’s symbolic lighthouse brims over with a Borghesian library of masterpieces, including unknown comics composed by Lorca and Picasso.

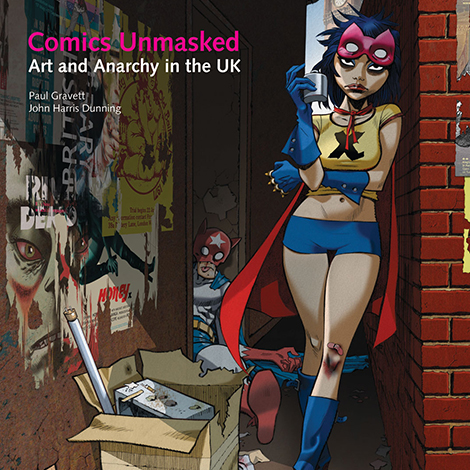

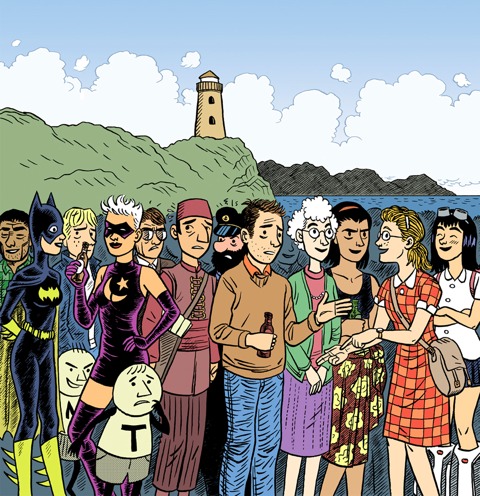

Horrocks soon found himself hired by New York giant DC to script, but not draw, commercial comic books like Batgirl (#39-#57, a 19-issue run, extract below) and Hunter: The Age of Magic (one mini-series and 25 issues), a dream ticket for some, but for Horrocks a nightmare he had to escape. “It almost killed me as a cartoonist. I was writing in a voice that wasn’t mine and felt trapped in other people’s wish-fulfilment fantasies. Eventually, I lost my cartooning voice entirely, and my lifelong faith in stories and art.”

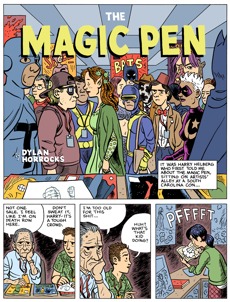

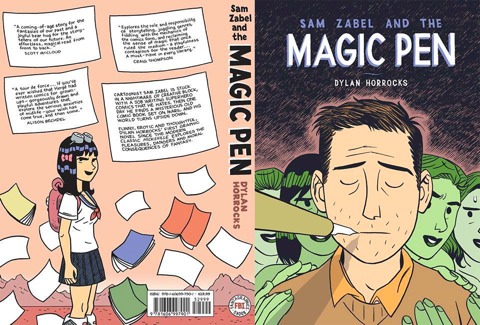

To rebuild that faith and find his voice again, Horrocks eventually devised another metafictional myth, not a paradise, but a pulp-confessional fairytale about the joys and pitfalls of making comics a playground for your wildest imaginary desires in Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen (Fantagraphics/Knockabout). As Horrocks reveals in his new Strip for ArtReview magazine (below), “The legend of the Magic Pen has been passed by word of mouth from cartoonist to cartoonist for generations, offering a small glimmer of hope to struggling freelancers and frustrated dreamers.” All it takes is one puff of breath and paper and ink become flesh and blood and a creator can step inside his panels and consort with his characters.

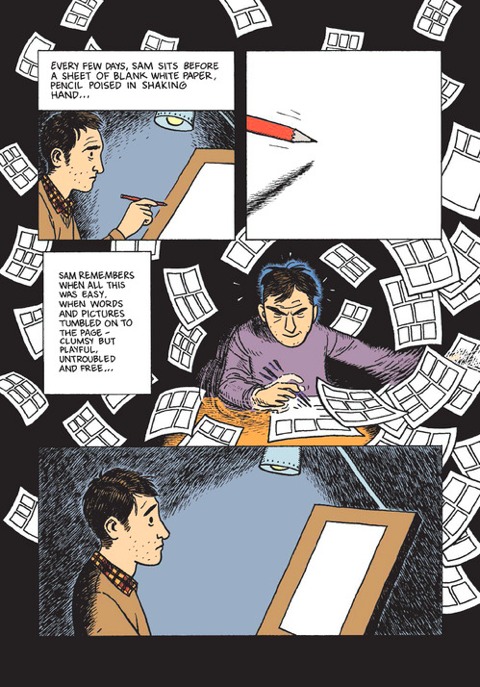

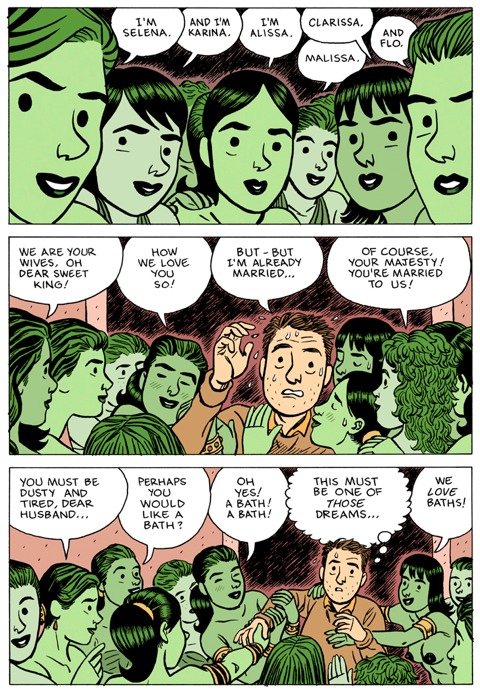

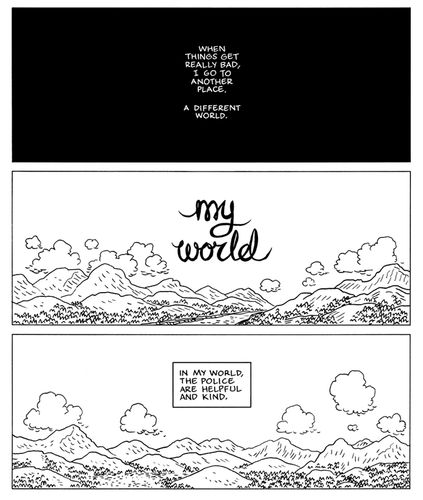

Sam Zabel plays Horrocks’ alter-ego, frozen with cartoonist’s block and torn between the need to express himself in marginal autobiographical strips and the need to pay the bills by working on corporate-owned franchises. Zabel is whisked between genres, confronting the male gaze and its escapist clichés, whether as a pneumatic super-dominatrix, a green-skinned Martian harem (below) or a manga fan’s tentacular pornotopia.

Horrocks admits, “I allowed the story to take me in directions that made me distinctly uncomfortable, because I felt the need to be honest. I’m fascinated by artists who allow themselves to be indulgent, who dive deep into their fantasies and desires. They’re like spelunkers exploring the depths of our strange mind-body cave-systems. But do I worry about what we’ll find down there? Do I believe we should always bring it to the surface and share it around? That’s more complicated.”

At one crucial stage, neither Horrocks as narrator nor Zabel as his avatar can bring themselves to assert that we are morally responsible for our fantasies. Nevertheless, thanks to the magic of comics, that unvoiced opinion and those fantasies appear on the page. “I don’t want the reader to try and work out my answers, I want them to explore the questions for themselves. To experience the pleasure and power of fantasy, even as they question what it means. I don’t trust simple answers, I just think it’s a conversation worth having.”

Stimulating doubt and debate, Horrocks’ meditation on the power of images and stories finally raises cautious hope for the fresh magic awaiting in every cartoonist’s pen. But Horrocks cautions, “If you’re feeding me a wish-fulfilment fantasy, it better be your wishes, or it won’t ring true. It’s very hard to lie about desire. Mind you, people fool each other with fake orgasms all the time. So who knows?”

‘The Magic Pen’ for ArtReview

Click images to enlarge.

Web Exclusive

Here’s the full text of my email interview with Dylan Horrocks - with many thanks for his engaging, sometimes equivocal answers - and his further questions!

Paul Gravett:

From imagining a charming, modest, remote and perhaps unattainable utopia for comics in Hicksville (above), in Sam Zabel and The Magic Pen you employ an avatar to explore the less idyllic realities of making comics more or less for money. What were the obstacles and dilemmas you faced to finding your way back to making comics again and what enabled you to overcome them?

Dylan Horrocks:

After Hicksville, I spent several years writing commercial comics for Vertigo and DC, which was a fascinating experience (and paid off a lot of bills!), but almost killed me as a cartoonist. I was writing in a voice that wasn’t mine, and spending a lot of time feeling trapped in other people’s wish-fulfilment fantasies. Eventually, I kind of lost my cartooning voice entirely, and also lost my lifelong faith in stories and art. I couldn’t trust stories any more. Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen was my attempt to find my way back.

So much has changed in the world and in comics since you serialised Hicksville in black and white in Pickle. Now Sam Zabel was serialised on the internet in colour and is being published in multiple simultaneous editions worldwide. What are your perspectives on these changes, for better and for worse?

I remember when photocopying machines became plentiful (and cheap) in the 1980s, which led to a blossoming of the small press, mini-comics and zines. It felt like a revolution. But the internet takes that to a whole nother level. Not surprisingly, many publishers and retailers are struggling to adapt, but the main thing for me is the explosion of new and incredibly diverse artists who are embracing comics and are taking them in countless new directions online. Living in a tiny country at the bottom of the world, I’m especially conscious of the possibilities opened up by the internet to empower previously marginalised artists and writers: not just in terms of nationality, but also gender, sexuality, ethnicity and more.

Not that everything’s peachy, of course. Governments and corporations are doing their best to bring the internet under their control, and things are changing quickly. Interesting times…

The other huge change in comics since the days of Pickle is the rise of the graphic novel. Twenty years ago, the idea that comics would be regularly reviewed in classy literary journals and nominated for major book awards seemed as utopian as Hicksville. I still find it hard to believe. And I still love finding some strange little hand-stapled mini-comic at a local zine-fair….

God of Manga Osamu Tezuka once said we are living in the age of comics as air. He was partly warning about the medium’s potential polluting effects. What are your thoughts about his concern?

I don’t worry about the effect of comics, so much as I worry about stories and art in general. We live and breathe them (hence Tezuka’s beautiful metaphor); they shape and filter our experiences, thoughts and feelings, our politics and ethics, religion and science. I can’t understand writers and artists who never feel a vertiginous anxiety about the power of images and stories. It scares the hell out of me. But oh my God, I love them so much…

Speaking of anhedonia, part of me wishes I could enjoy my favourite superheroes still. For me the big moral issue is the injustice of Disney and Time-Warner-AOL towards the (co-)creators of these characters which has tainted their continuing sagas. Out-of-court settlements or failed lawsuits do not help. Can we really ever go back to these fantasies?

Around the time I started writing Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen, I spoke at a conference in Christchurch, on the future of New Zealand literature. I was deep in my crisis of faith in stories, and so instead of concentrating on comics or novels, I talked about Dungeons and Dragons, and other fantasy games – on the creation of imaginary worlds as an artform in its own right, and a way to evade the seductions of story-structure. Afterwards, someone in the audience said he had played D&D obsessively as a young man, but then one day he simply lost the ability to enjoy it. He could no longer suspend disbelief, and suddenly it just seemed silly. “Sometimes,” he said rather sadly, “I wish we could switch our post-modernity on and off at will.” I don’t know if it’s post-modernity or simply a matter of getting older, but I know what he means. Some days, I’d give anything to be able to go back. But then I start drawing, and, in a way, I have.

I worry and wonder about the brainwashing from the cradle - or the push-chair and baby clothes - of Spider-Man, Batman et al on kids today. Am I stupid?

You’d be stupid not to worry and wonder. Which is not to say it’s actually a problem. Maybe it’s wonderful? And yet… and yet….

Only in America are two global multi-corporations set on perpetuating a limited range of franchise brands all around the world. True, there are some long-running, big multi-author brands elsewhere - Monica in Brazil, Pokemon in Japan, Blake & Mortimer in France/Belgium, Tex, Diabolik or Dylan Dog in Italy, I suppose Beano and Judge Dredd in the UK - but they have not been imposed worldwide or dominated their local creative scenes quite so much. Should we be worried about this tendency? Will this change or will these never-ending stories never end?

The thing I find most difficult is the way these characters that dominate our shared imaginative space are all corporate franchises. I’d feel a lot more comfortable with it if Batman and Captain America were in the public domain. A couple of hundred years ago, the key cultural icons were in the shared commons. Today’s icons are treated as private property, owned by neither the creators nor the countless fans who invest so much in them, but by huge corporations. I love it when fans subvert that relationship, taking creative possession through cosplay or fanfic. Often, that’s where the most interesting versions of the popular superheroes can be found (one example: New Zealand cartoonist Robyn Kenealy’s brilliant webcomic Steve Rogers, American Captain).

Neither you nor Zabel can bring yourselves to state in the book that “We are morally responsible for our fantasies” - and yet of course, thanks to the magic of comics, that unvoiced opinion still appears on the page. You also use comics both to show Sam’s erotic fantasy and then question and confront it.

I never wanted The Magic Pen to present a simplistic answer to that question. The book opens with two contradictory epigraphs: one from Yeats, the other from porn performer (and creator) Nina Hartley. Together, they start a conversation, a debate. And the book then keeps that conversation going: expanding, bringing in different perspectives and complications, raising new questions. I don’t want the reader to try and work out my answers, I want them to explore the questions for themselves. To experience the pleasure and power of fantasy, even as they question what it means. I don’t trust simple answers, I just think it’s a conversation worth having.

Are you against state or industry censorship of comics? What about self-censorship? Did you censor yourself in The Magic Pen?

I believe the dangers of state (and industry) censorship of comics are far greater than any benefits. Self-censorship is more complicated. I don’t know that it’s possible to avoid. There are pages in The Magic Pen that I redrew several times because I felt the first version had gone “too far.” I wanted to strike the right balance, to find the right tone. But I also allowed the story to take me in directions that made me distinctly uncomfortable, because I felt the need to be honest. I’m fascinated by artists who allow themselves to be indulgent, who dive deep into their fantasies and desires. They’re like spelunkers exploring the depths of our strange mind-body cave-systems. But do I worry about what we’ll find down there? Do I believe we should always bring it to the surface and share it around? That’s more complicated.

I wonder if the freedom to fantasise all too easily lapses into overused clichés and reinforces stereotypes? These are shared, populist, deeply ingrained in cultures, and perhaps hard to shake off or subvert? Is it inevitably easier to stick to fulfilling expectations rather than challenging or disappointing them?

I don’t think that’s necessarily a problem. The repetition of familiar trope and clichés is a key element in folk art and storytelling; it’s part of how we explore the landscapes of our culture and ourselves, by returning to the same pathways over and over, getting to know their every nuance intimately. Those comfortable places can be interesting and revealing, and also healing and affirming. Of course, challenging them is just as revealing – but I don’t think it negates their value.

For me, the most important thing is whether a particular fantasy is honest. Even if a writer, cartoonist or pornographer is doing nothing more than repeating the usual clichés - if they’re doing so because that is what resonates most deeply for them, then I figure it’ll probably be interesting and powerful. But if they’re just trotting out what they think the market wants, or what their editor is asking for, I’m less likely to be interested. If you’re feeding me a wish-fulfilment fantasy, it better be your wishes, or it won’t ring true. It’s very hard to lie about desire. Mind you, people fool each other with fake orgasms all the time. So who knows?

I believe you are also working on an erotic graphic novel - what is your moral compass for this? What are your views on erotic/porn comics, say Manara, or Moore/Gebbie’s Lost Girls, and the underexplored potential of this subject in comics?

I like Lost Girls very much. Manara is more complicated, but I can’t deny the power of his obsessive single-mindedness. There’s a long history of erotic comics, going back as far as the form, but I still believe the subject has enormous potential. Sexuality is so complicated, so important, so fascinating, so delicious and disturbing – and our ambivalence about exploring it so extreme – it amazes me that everyone doesn’t write about it.

As for my moral compass? Writing and drawing is like exploring uncharted territory. If you don’t know where you’re going, a compass can only help you so much. It’s important to keep your eyes on the terrain….

Many thanks, Dylan, and we’re looking forward to seeing you in the UK when you attend the 2015 Australian & New Zealand Festival of Arts in London from May 28th to 31st.

Posted: January 9, 2015The opening Article first appeared in ArtReview Magazine.

Photograph of Dylan Horrocks © Grant Maiden.