Learning To Read From Comics:

Comics As Gateways To Literacy

The idea that comics can be gateways to literacies - both verbal and visual - for those of any age or ability learning or struggling to read is nothing new. Seventy years ago, one Florence Morrison Hogan from the U.S. Department of Education wrote an MA thesis at Atlantic University on ‘A Survey of the Literarture on the Use of Comics as a Means of Promoting Interest in Reading’ (you can download her entire thesis here…). The title and contents pages and bibliography were shared by David Best on the Facebook group, Comics History Exchange. Morrison Hogan lists eighteen references dating back to December 1937 on this topic.

Only the year before, in 1944, as Gene Luen Wang mentions in his comic below, the august Journal of Educational Sociology devoted a whole issue to comics. You can read one of the articles therein here: ‘The Comics and Instructional Method’ by W.W.D. Sones. And on the Comics History Exchange group, Maggie Thompson shared this related story: “I’ve tried to track down information from time to time on the Superman English workbook from that era. The experiment was deemed a “failure” because the kids were so excited, many took workbooks home and completed them in a day or two. Which meant the lessons weren’t being doled out properly as a back-up to instruction.”

These provide evidence that the ground work and groundswell were there for comics in the classroom, but there have been setbacks along the way, especially due to the demonising of comic books in America and elsewhere which increased after World War Two. Thankfully, many educators are currently embracing comics more and more. A recent documentary Comic Book Literacy invited Françoise Mouly, Art Spiegelman and others to address the need for greater visual as well as verbal literacy through the comics medium.

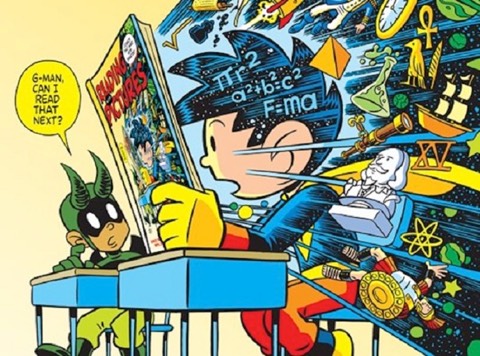

As part of this drive, last year Andrew McMeel published Reading With Pictures: Comics That Make Kids Smarter, edited by Josh Elder. As the introduction explained, “Comics have gone from ‘scourge of the classroom’ to legitimate teaching tools, and the Common Core State Standards for scholastic achievement now explicitly recommend their use in the classroom.”

This full-colour volume features ‘more than a dozen short stories (both fiction and nonfiction) that address topics in Social Studies, Math, Language Arts and Science, while offering an immersive textual and visual experience that kids will enjoy. A 145-page downloadable Teachers’ Guide includes standards-correlated lesson plans customised to each story, research-based justifications for using comics in the classroom, a guide to establishing best classroom practices, and a comprehensive listing of educational resources. Tracy Edmunds provides a handy beginners’ instruction manual on how to read comics.’

And in Britain, as well as Dave Gibbons as our first ‘Comics Laureate’ and schools voting for the annual Stan Lee Excelsior! Awards, Comics Literacy Awareness (CLAw) was founded last year as an exciting new literacy charity by a group of passionate and highly experienced trustees from the fields of education and comics. The mission of CLAw is to dramatically improve the literacy levels of UK children through the medium of comics and graphic novels. CLAw also aims to raise the profile, image and respectability of comics and graphic novels as both a valid art form and as works of literature.

Change is also happening here on the frontlines, in our classrooms, led by forward-thinking teachers who want to reach reluctant readers and awaken a passion in them for reading. During Comica Festival 2014, at the inaugural discussion day S.M.A.S.H. at The Barbican Library, I got talking with two such London schoolteachers who were introducing their young pupils to graphic novels. They each agreed to let me interview them about their challenges and achievements in doing this. To respect their confidentiality I have removed their names and specific schools. I think their interviews are very revealing, worrying and inspiring. Both of them hope that their experiences can inform and encourage others in education to embrace and pursue for themselves this vision of comics as powerful and effective tools for literacy.

Interview 1:

Please introduce yourself, your position and background and the course and kids you teach.

I teach high school English in one of the poorest boroughs in the city of London. I teach years 7-11 (11 to 16). I’m 33 years old and originally from Canada. This is my 4th year in London and have been working at the school I’m currently employed at that whole time.

How did you persuade your Head of Department to pilot a project around graphic novels?

I’ve actually been trying to get graphic novels into the curriculum since arriving at the school. Originally it was almost impossible to get anyone to listen. English Curriculum is so rigid in this country that it almost leaves no room for new ideas or new forms of literacy. I steadily kept at it, working on the 2nd of department quite a bit who started championing my idea. The final straw was that it is almost impossible to get kids, especially white British boys, to read. This has always been a flagged group. So finally my department head came to me wanting a plan for how to introduce Graphic Novels into the school with the hopes of getting kids to read. My original plan was to do one graphic novel in each year group from years 7-9. I was told I could have year 7’s and we would see how that went. I have a teacher friend at a different school and when I told him what I was doing, he told me he’d like to help. So together we created a 6-week scheme of work around “The Arrival by Shaun Tan and Mouse Guard by David Peterson.

What resistance did you meet and how did you counter it?

My initial resistance came from teachers. Basically a lot of them couldn’t see the educational merit within them. Also they were texts which they themselves had little knowledge of. I had to break it down to them. Educationally comics are great because it teaches kids inference skills. Most kids in year 11 can’t read between the lines of a book. And in year 11 it’s almost impossible to teach those kind of skills to the kid. At that point you are just bailing the water out of the sinking ship, while they row it across the lake hoping to make it across. But if you can teach those skills young, then they will be embedded in the kid once they reach year 11. It’s much easier to infer from a picture. Kids are way more used to it from TV or just their normal interactions with others. For example, if someone tells me they are fine but appear to have been crying, then they probably aren’t. Kids get that concept and even in really subtle drawings they pick it up. So I had to argue that and get my co-workers to understand what we were trying to accomplish.

One member of leadership actually was completely against it and tried to torpedo the whole project, based on studies she had read that showed graphic novels were not good for EAL kids (English as an Additional Language) and that high-ability kids (smarter children) find comics boring. My response to her was I was not aware of any such articles and all such educational research I’d seen points to comics as a great tool for EAL and high-ability children, because the EAL kids do not necessarily have to rely on the words and the higher kids become engaged with the more subtle nuances of the art. After that meeting I never heard anything more about that and she never actually forwarded me any of that research she said she had read.

What were the initial reactions of your pupils towards comics?

Initially, to my surprise, kids weren’t that into it. they saw it as baby stuff. This soon changed. They loved it. We read Mouse Guard last September and now, in June, they still ask me if we can read it again and constantly tell me it’s the text they enjoyed the most all year. Also year 10’s and 11’s who saw what I was reading with my year 7’s asked to read it. They got jealous that we don’t do anything like that with them now and didn’t when they were in year 7.

Had any of your students read comics already or were any reading them now? Were boys less interested in comics than girls for example?

None of my kids where reading comics. I believe a lot of parents got requests last Christmas for the next couple of Mouse Guard series. I made sure to let them know that if they enjoyed the book, they could continue reading at home. Which was one of the main reasons we wanted to do this. Get kids wanting to read at home. The book seemed to have an impact on both boys and girls. It got everyone excited. Having said this, I also run a comic club at the school which initially was almost all girls but as the year has progressed is now much more equal genderwise.

Why do you think a whole generation of British kids seems to have grown up without reading comics?

That’s a hard question because I haven’t grown up here but my feeling is that there was just no reading material period. There is just a large lack of literacy period. No books, no magazines, no newspapers. I remember picking up a newspaper after my Mum or Dad had finished reading it in Canada and turning to the funnies section and even when I couldn’t read it, I would enjoy the pictures. There is none of this in most homes it appears, especially in the area I work. Lastly, kids are exposed to these characters through TV and movies and then never make the jump to the comic shop.

How did you introduce comics to the students - did you explain distinctions like graphic novels or manga?

The first week we had to introduce comics to them. They didn’t know how to read a comic. They didn’t know how to transition from panel to panel. We had to introduce a new language and terminology to them. Luckily they picked it up fast. We didn’t get into manga. There was just to much to look at. Though I have introduced manga into my comic club.

Why did you choose to start with Shaun Tan’s wordless - or at least English text-free - graphic novel The Arrival?

Firstly because it’s great! But also because kids are more familiar with picture books. For these kids comics are a completely new form of literacy, so you can’t just chuck them straight into the deep end. So it’s helpful to scaffold it for the kids. Start with just pictures and get the kids thinking about how to read them and have the story make sense in their heads. The kids begin to work on those inference skills I talked about previously and when we got to Mouse Guard, they understood that they had to use the pictures and words to complete the story. Plus it’s an excellent text for EAL students.

What were your experiences teaching with The Arrival and what did you learn from them?

We have 2 advanced year 7 classes. One of the teachers pretty much spent all 6 weeks on The Arrival. Not because she didn’t want to read Mouse Guard but because her class fell in love with the book and they began to dissect and discuss almost every page in class. To me that’s still a success, because without even reading a single word, those kids where engaged and in my opinion still working on literacy skills. That teacher got amazing stories out of that class. She actually left the school at Christmas because she was moving to Wales and I believe she took the whole scheme of work with her to her new school.

Personally I loved teaching The Arrival. There is just so much room to explore for the kids. I love novels, but I can understand why some kids may have an aversion to them. The story is there on the page. But with something like The Arrival you are allowing the child to create their own story in many ways. I started by stating that the English curriculum is rigid. There is almost zero room for a kid to use his or her imagination. Well in something like The Arrival they can.

How did you proceed onto David Petersen’s Mouse Guard? What made you select this in particular?

Lots of research. So I started by picking up a lot of different comics. I Kill Giants, American Born Chinese, Mouse Guard, The Runaways. I decided I wanted the book to challenge the students, be age-appropriate and also be fun. Mouse Guard hit on all three points. Though I was close with American Born Chinese. In the end you’ve got to go with swashbuckling mice. The art is beautiful to look at and the story is completely original yet has a familiarity to it that I felt would hook the kids right away. Petersen created this enormous world and we got to play in it. That’s how you engage kids.

How did the rest of this ‘trial’ project around Comics As Gateways To Literacies develop and what ‘results’ were you able to report back?

Well the comical bit is that even with such success from all parties, both kids and teachers, it’s been a struggle to get it expanded to higher grades. We are keeping Mouse Guard for next year but nothing more has been green-lit. In the next few weeks we will be deciding texts for next year and at that time I’ll be fighting for expansion into years 8 & 9. I’m hopeful I can convince them to let me do something for year 8’s, but I don’t think I’ll be able to get them to agree to reading a graphic novel in year 9. Education moves at a glacier’s pace here and comics just can’t catch a break.

What were the school’s reactions to this and how have comics been introduced more broadly into the curriculum?

Well to go further, even though it was a success in English, I’m not 100% sure leadership is aware of the project. My personal thoughts are that this is why I’m not allowed to expand it to other grades. People still cling to old thoughts and ideas.

Have you considered adding a comics-making element to this?

Yes, for my comic club I think I will. Also I was thinking of purposing this comics-making element to the art department in order to foster an English/Art cross-departmental project.

What are the opportunities and challenges ahead for making greater use of comics in the classroom to stimulate visual and verbal literacies?

The challenges are the same as always, that they are constantly seen as something with little educational value by most. Also my goal is to read them with year 10’s and 11’s eventually, but the governmental curriculum doesn’t allow that. It’s just a small set of novels, poems and plays and nothing else. That’s the frustrating part.

What resources have proved useful - reports / conferences / websites / textbooks / teachers’ notes - as you take this forward?

Definitely our Department meetings. We were able to discuss what was going on as it happened. Also really the kids have become our best resource. Thir pushing for more of these kinds of books and telling their parents and other teachers.

Do you see the teaching establishment coming round to seeing comics as a useful tool in encouraging reading and inference, to make young people more media-savvy?

Sadly no. Not in this country. My colleague and I did something that I feel was highly successful. All the feedback I got back from other teachers, kids and my department head was how successful our Mouse Guard unit was. Yet, even with all of that, I’m going to have to fight to expand it to other grades.

How do you envisage this progressing still further ideally? What other needs could comics address in the classroom?

Ideally, I would love to see kids do one graphic novel a year from year’s 7 to 11. You know, as a teacher, I have to teach Shakespeare, poetry, novels, etc, every year. Well why not add a graphic novel to that? Especially in this day and age when we have so many amazing pieces of literature that also just so happen to be graphic novels/comics. Could you imagine teaching Watchmen to year 11? That’s my dream and I believe it can happen. This all became a possibility to me when I was back in Vancouver, talking with someone who was teaching Watchmen and had gotten one graphic novel into each year group. I asked him how he did it and he told me he became the Head of English. In other words, I just have to open my own school. Which in this country is actually possible.

Interview 2:

Please introduce yourself, your position and background and the courses and kids you teach.

I am 32 years old and have been teaching for 6 years, two in Canada, two in America and now two in Britain. As well as English I have taught history and religious studies. Currently I teach English in East London and the students I teach are statistically the most at risk in the entire country. One of the biggest issues I see in the classroom, and in the school as a whole, is the insecurity of the students. Their insecurities are the biggest hurdles they have to overcome both socially and academically. Socially, the majority of students come from difficult backgrounds and homes and this has affected the way they build relationships, especially with adults. It is difficult for students to trust adults, navigate the appropriate power dynamics and not to take constructive feedback personally. Academically speaking, it is often hard for the student to get the appropriate differentiation and support they need, for they are being pushed ahead based on their target, and the teaching becomes destination-focused instead of process-oriented. Students are basically told what to write and how to write instead of being taught how to do it themselves, and this leads to a negative cycle – never allowing the student to become an independent learner.

For Years 7 and 8, students are divided into sets from 1 (being the top students) to 4 (being the lowest). Additionally there is a 5th set, and this class is reserved for the most vulnerable or special of our students. Furthermore, from Years 9 to 11 the students are divided amongst 8 sets, plus a 9th set - again for the most vulnerable students. Students are split into the Sets based on levels generated from a standardised test taken in Year 6 known as a SAT. To put it into context, these results are taken as the ‘Word of God’ when it comes to the potential outcomes of target grades and GCSC scores for the students, at least at my school. However these scores are ridiculously unreliable: you will have students in Set 2 with targets of an A or B on their GCSC, but in Year 9 (13-14 years old) with the reading level of a 6 and 7 year old. Additionally, it is extremely hard to move a student’s set as well. For example, take the prolific examples of the student with a high targeted grade and low reading and writing ability: this student is in set 2 based on their Year 6 SAT, but their reading and writing assessments in years 7, 8 and 9 shows that they should be in Sets 6-8. It is near impossible to move them down to a more appropriate set.

How does this occur you ask? The pressure on teachers to have their students reach their targets has become paramount in the British Education system. In many schools, including the one I teach in, teachers’ pay raises are specially tied to the achievement of students. Moreover, League Tables have become a prominent benchmark for school success, and in Primary schools SATs are the scores which rank you in your league table. The outcome of such measuring systems has led to schools becoming exam factories. Sadly, Primary schools take this route to achieve high standards, and then Secondary schools repeat the problem to maintain an upward progression. This has been a problem at the school I teach in English that we are hopefully moving away from. Currently students will read or review the same literature and poetry from year 9 to 11. That means that students will read the same poems over and over again, as well reading A Lady in Black and An Inspector Calls three times by the time they have to take the GCSC. Additionally, if you can believe it, for years 10 and 11 students will have at least 12 weeks of language exam prep; 12 weeks of preparation each year for a test that only has 6 questions.

How did you persuade your Head of Department to pilot a project around graphic novels?

Relentless nagging! Hahaha. Funny, but true! Last year, our Year 7 students read one novel, and it was divided by Sets. Our Set 1 classes read A Little Piece of Ground by Elizabeth Liard (Blurb from Amazon: ‘12-year-old Karim Aboudi and his family are trapped in their Ramallah home by a strict curfew. Israeli tanks control the city in response to a Palestinian suicide bombing. Karim longs to play football with his mates – being stuck inside with his teenage brother and fearful parents is driving him crazy. When the curfew ends, he and his friend discover an unused patch of ground that’s the perfect site for a football pitch. Nearby, an old car hidden intact under bulldozed buildings makes a brilliant den. But in this city there’s constant danger, even for schoolboys. And when Israeli soldiers find Karim outside during the next curfew it seems impossible that he will survive’.), and Sets 2-4 read My Week with The Queen by Morris Gleitzman (Blurb from Amazon: ‘Colin Mudford is on a quest. His brother Luke has cancer and the doctors in Australia don’t seem to be able to cure him. Sent to London to stay with relatives, Colin is desperate to do something to help Luke. He wants to find the best the doctor in the world. Where better to start than by going to the top? Colin is determined to ask the Queen for her advice’.)

Personally I did not believe either of these books was suitable for our year 7 students. A Little Piece of Ground would require a lot of social and historical contextual lessons to provide students with the necessary background to understand the narratives. I took a year-long history course at University examining Israeli and Palestinian conflict and have a hard time comprehending how an 11 year-old could fully grasp the complexities of this issue in 2-3 context lessons. On the other hand, Gleitzman’s Two Weeks with the Queen is best suited for Year 5’s. It is not at all relevant to the lives of the young people I teach, nor are the plot or narratives engaging in any way.

It was under these pretences that I pitched the idea to my department head. The department head that I originally pitched the idea to became a ‘lame duck’ department head by the beginning of October and a second within the department was promoted. This led to me having to pitch the project again, and as well as stating what I did above, I argued strongly for the benefits of visual literacy. Many of the students I teach struggle with visual literacy, even when watching a film it can be difficult for them to follow what is happening. Paired with the low reading abilities, I personally think this reflects how students are not being read to as children. For those of us who were lucky, we were read to as children, and often those times are spent discussing the images that are paired with the short descriptive sentences. For example ‘look at the beautiful colours. What colours are those? Why do you think the dragon is that colour? Does the dragon look happy or said?’ Etc. etc.

Another benefit is the pairing of images with language. An area where this is highlighted is the comprehension of feelings. Often my students’ feeling descriptors are simply ‘sad’, ‘happy’ or ‘mad’; when they encounter more complex and ambitious vocabulary describing one’s feelings they are unable to access the sentiment being presented by the author. I believe this is the great advantage of using comics or graphic novels for students who may have difficulty understanding a word such a ‘morose’ or ‘exhilarated’, but if it is paired with an image they can associate the word to, all becomes evident. In conclusion, another element I factored in, especially when it came to Shaun Tan’s book The Arrival, was the ability to use his work to begin teaching students the importance of implicit and explicit meanings.

What resistance did you meet and how did you counter it?

I met resistance from my department head, fellow English teachers and an administrator. However, the majority of this resistance did not occur until the week before the graphic novel unit was about to begin. I chalked this resistance up to two elements: Politics, of which schools are rife, and ignorance, of which schools are also rife! The sad part about the criticism and resistance I faced was that it was evident, by their arguments and concerns, that they had not even read through the scheme of learning which my friend and I developed, nor had they looked through the six weeks of powerpoint lessons we designed. It got to a point where I would have quit if the unit was abandoned. My department head’s concern was they wanted the students to ‘engage with a whole text’, and I assured them that both Shaun Tan’s The Arrival and David Petersen’s Mouse Guard were both whole texts. I cannot fully explain my colleague’s resistance, only to assume they wished to do what was comfortable. I prefer to think it was that, instead of something personal. Haha.

From an administrative perspective, the administrator who did not like the graphic novel unit did not approve of the unit, because it would not match anything students would need for their GCSC’s in year 11. It was at this point I felt like I was arguing with a brick wall, for there were many skills that applied to the GCSC embedded into the unit that we had developed; plus we were discussing year 7’s! I believe there were only a few factors that allowed this unit to be taught: one, my consternation, which led to me threatening to quit, as well as being more aggressive in the exalting of the benefits; two, an assistant year lead who believed in the project; and third, no one in leadership could develop anything better a week before the unit would begin. Consequently, some changes were made. Set 1 classes continued to read A Little Piece of Ground, while the reading assessment based on Tan’s Arrival was modified with an additional extract from Unpolished Gem by Alice Pung. All in all, despite the drama that unfolded around the unit, I was happy it was taught.

What were the initial reactions of your pupils towards comics?

The initial reaction of the students was amazing! They were all so excited; I had built up the unit with posters around the school. When students first realized that The Arrival had no words they were flabbergasted. They loved the idea though! It was such a wonderful way to teach implicit and explicit meaning. The students would approach each panel like a treasure hunt, they knew that there was so much to be discerned from the image or images that Tan presented and they relished the discussions and activities used to decipher the theme and plot.

Had any read them already or were any reading them now? Were boys less interested in comics than girls for example?

The students had not read any of the graphic novels we were studying previous to being taught, however some have now purchased the next instalments of Mouse Guard. Our library has also purchased four additional Mouse Guard graphic novels. I would also say that the excitement and engagement transcended any racial, cultural or gender pretexts.

Why do you think a whole generation of British kids may have grown up without reading comics?

This is a good question and I think the answer is multifaceted. Firstly, I think there is simply a large portion of the population that does not read, and I think it is hard for them to engage with their children in reading of any kind. Secondly, I think it is not often associated in people’s minds with the growth and development of literacies in young people. I myself was a late reader, age 9, then subsequently a reluctant reader, and never once was a comic presented to me as a written form with which to engage. I can only assume, but I think it may be the case, that in the past years the literary milieu may have viewed comics as being something completely ‘other’ to literature and that may have been reflected in the accessibility of comics in bookshops. I personally did not have a comic shop anywhere near my childhood home, while at local high streets or shopping centres there were various bookshops, none of which carried comics or graphic novels on their shelves. Last but not least, we must not underestimate the ease of dropping a child in front of a television, computer or tablet.

How did you introduce comics to the students - did you explain distinctions like graphic novels or manga?

Many of my students were already familiar with comics. As of late, with the addition of this graphic novel unit, our librarian had been stocking more graphic novels and comics. Additionally, manga are extremely popular books for the students to borrow, particular boys and students with lower reading abilities. The most popular manga borrowed by students are Naruto and Bleach, followed closely by Dragon Ball Z, Case Closed and One Piece. Despite the fact that many of the students did read manga, it was still imperative to teach them how to read a comic. For this we utilised Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud (above). It was an amazing resource and it allowed us to have a framework on which to build and attribute examples.

Why did you choose to start with Shaun Tan’s wordless - or at least English text-free - graphic novel The Arrival?

We choose to begin with Shaun Tan’s The Arrival because it simply would be the most enriching in regards to engaging the students in this medium. Through The Arrival students would be able to become more adept in the practice of visual literacies and this would be beneficial leading into David Petersen’s Mouse Guard, for we were able to scaffold the visual literacy skills achieved in The Arrival to allow students to interact more effectively with the language in Mouse Guard.

What were your experiences teaching with The Arrival and what did you learn from them?

.

Teaching The Arrival was one of the most exciting moments of my teaching career. The anticipation and excitement the students had coming to class every day was wonderful. They were captivated by the images and eager to see what awaited them each day with each turn of the page. To see the students’ confidence grow in identifying implicit and explicit meanings was rewarding. Watching students debate and discuss the meaning and significance of certain panels and the images therein was profound. Likewise, when the students had to assign language to the panels through speech/thought bubbles and captions, whether it was their own words or those borrowed from a song or poem, the result was enlightening. The narratives developed, even from the same pieces of text, were varied and carried their own themes and tone. So, the benefit of The Arrival was twofold: it allowed students to develop their visual literacies, but it also allowed them to develop and grow their own sense of imagination, in which sadly many of the students lack confidence.

How did the rest of this ‘trial’ project around Comics As Gateways To Literacies develop and what ‘results’ were you able to report back?

My friend and fellow teacher and I wanted to do something that would inspire students. We realised the students in our areas faced major disadvantages regarding literacy. We believed that comics and graphic novels would be a great opportunity to build the skills necessary to access other pieces of literature. I would say that in the classes I examined, it helped the students to understand the choices authors make, and why they would use implicit and explicit meanings. This skill has permeated through the other units of work. Additionally, for some of the weaker students, it was an opportunity to prove and realise their natural abilities without being constrained by the written word. This freedom ignited the confidence needed to engage and interact with written text, and the result has prevailed. Moreover, the development of vocabulary regarding thoughts and feelings around many of the images, particularly The Arrival, set a base that would allowed students in the future to utilise more ambitious vocabulary in new pieces of writing.

What were the school’s reactions to this and how have comics been introduced more broadly into the curriculum?

My school and department have carried on as if the unit and success that we had within the unit never happened. It was welcomed with great anticipation and excitement on new parents’ evenings, but at the end of the day it is not something admin is interested in, as it’s not something that the Ministry of Education is interested in. Most administrators (my school has 1 head teacher, 2 Deputy Heads, 3 Assistant Principals, and 2 Associate Assistant principals) did not get their roles because they are trailblazers. To get someone to fight for something new, progressive and ‘edgy’ is almost impossible. It is sad, because there are so many great graphic novels that can be used to enrich other subjects, particularly history and geography.

Have you considered adding a comics-making element to this?

I did and I had scheduled into my timetable an enhanced class to teach comics-making once a week for an hour. However, my timetabled hours already exceeded the legal amount of hours required and it was cut.

What are the opportunities and challenges ahead for making greater use of comics in the classroom to stimulate visual and verbal literacies?

Challenges ahead are the perception of comics being a lower level text, the insecurity of teachers teaching something new, and the reluctance of administrators to engage with materials that challenge the establishment. Despite these challenges, I believe that this is only the start when it comes to comics as a teaching tool. The more teachers are teaching comics, the more resources are developed and the more evidence is correlated to support its effectiveness will only empower others to introduce comics in the classroom.

Do you see the teaching establishment coming round to seeing comics as a useful tool in encouraging reading and inference, to make young people more media-savvy?

Sadly, I do not see the teaching establishment coming around, at least in Britain. As we speak, the education system is quickly becoming more and more corporatised and standardised in terms of organisation and presentation. The rise of Academies and programmes like Teach First and School Direct are ushering an age of ‘yes’ men and women, where individuals are driven to achieve positions in management instead of developing creative and critical pedagogy in the classroom. This corporate attitude, paired with the active disregard of unions and teachers’ rights, will lead to a less qualified, less creative teacher in the classroom. In connection, the new GCSC reading list developed by the Ministry of Education harkens back to the old days of education where modern classics like Of Mice and Men have been replaced by British Victorian era novels such as Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. God forbid students learn that the ‘American Dream’ does not exist. (Don’t get me wrong, I love Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, but there are at least 3-5 words a page that a top set year 10/11 class is simply not going to understand). These older novels, paired with the rigidity of the rules within Academies regarding teachers’ practice, as well as the immense pressure teachers face to have their students reach targets, paints a portrait of an establishment that is moving backwards instead of forwards.

How do you envisage this progressing still further ideally? What other needs could comics address in the classroom?

I hope to see graphic novels and comics used to aid weaker students access more complex GCSC novels. Allowing them to use images in panels to contextualise the language they are reading. Additionally, stronger students would be afforded the opportunity to explore different literary structures, platforms and narratives. Comics could be used to promote British Social and Cultural Values, which is now an element expected to be embedded into every classroom lesson. In my own case, despite the fact that comics and graphic novels will not be taught in lesson, I plan on having two comic clubs next academic year, for underachieving KS3 students and for underachieving KS4 students.

Many thanks for both of you for so generously sharing your insights.

Posted: July 12, 2015