Bryan Talbot:

An Artistic Wonder From Wearside

One of my ‘Books Of The Year’ was Bryan Talbot’s Alice In Sunderland. In this ‘Bryan Talbot special’, I take a look at Bryan’s career in comics and examine Alice In Sunderland in detail. This is followed by a short interview with Bryan and concludes with a review of the Byran’s latest publication, The Art Of Bryan Talbot.

"Have you seen my book?" Lancashire-born and bred, Bryan Talbot has never been backward in coming forward about comics. Give him the slightest opportunity and he’ll be thrusting his latest project into your hands, enthusing about some initial designs, a proposal, a work in progress or maybe another finished and published opus. It’s all part of his genuine, infectious passion which has kept him crafting all manner of projects for over thirty years and which if anything are stronger than ever now that he in his fifties. It was maybe four years ago that I got another of Bryan’s private views over an Indian dinner during a Bristol convention. He stunned me and our fellow curryphiles with tantalising first glimpses of his latest and unquestionably most audacious graphic novel yet, Alice In Sunderland.

Last January, when I met Bryan again at France’s Angoulême International Comics Festival, in no time he was showing me yet another forthcoming comic he’s cracking ahead on and gave me sneak peaks at full-colour portraits for Grandville, an inspired reimagining of some of the first French anthropomorphic caricatures.

An engaging, confident performer himself, Bryan is excellent at presenting his work to the public in his solo illustrated lectures and in group discussions. Back in March, he joined a Graphic Novel Panel I hosted at the Bath Literature Festival. During this, Bryan intrigued me with the story of what had first prompted him to conceive that comics might become the graphic novel. His mind travelled back to 1966 and as a teenager reading the fanzine column in the imported American horror movie and fantasy magazine Castle Of Frankenstein. He related, "The news item itself took up about a quarter page and consisted of an illustration from the book (the title page I think) and a caption beneath. It didn’t use the term ‘graphic novel’ but said that (whoever it was) was adapting Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword into comic book form. That was what inspired me - the idea of a complete novel in one big comic."

So from an early age, Bryan was already envisaging the medium as something much more than brief, throwaway periodicals and began hatching overambitious plans. "I spent ages developing a pseudo-Tolkien epic that never came to anything. In 1971, when I was being interviewed for degree courses in Fine Art, I was telling the lecturers that I wanted to do this comic novel as a project. Funnily enough, my portfolio consisted entirely of abstract art, which I had absolutely no interest in but was what you had to do in the early 1970s if you were a fine art student. Of course, I got short shrift and didn’t get on a course. Which is why I ended up doing Graphic Design in Preston instead. But the idea of a “comic novel” stayed with me and it eventually materialised in the form of The Adventures Of Luther Arkwright." After the first volume of Arkwright was serialised in Near Myths from 1978, and then reprinted and completed in pssst! magazine in 1981, Proutt, alias Serge Boissevain, his charismatic wealthy comics-loving patron from France, published it in book form in December 1982 and helped support him so that he could complete this complex cult trilogy, compiled as "one big comic" in 1989.

Luther Arkwright

Despite hunting through his collection for me, Bryan couldn’t find that magazine item which had first sparked his belief in comics as novels. Luckily, thanks to the internet, I contacted Mike Scott, who runs a fine vintage monster mags site. He swiftly emailed me a scan of the precise piece from the 1967 Castle Of Frankenstein Annual, published in 1966, which I forwarded to Bryan. "Cor blimey! That’s it. It’s so familiar - I must have stared at it many times." Shown here, the item reports that "Science-fantasist Poul Anderson gets the comic-strip treatment in Tom Reamy’s Trumpet" and shows the splash page drawn in 1965. I discovered that science fiction author Tom Reamy (1935-1977) adapted Anderson’s The Broken Sword in his fanzine beginning in Trumpet No. 4 in April 1966. The artist was renowned fantasy illustrator George Barr, who drew three episodes unpaid over three years, totalling twenty-two pages, before the two of them left it unfinished. According to Jim Vadenboncoeur on www.bpib.com it was Barr’s first and probably last comic work.

Fortunately for us, Bryan Talbot has never stopped creating comics, from his beginnings in 1970s British fandom and undergrounds, notably on the Chester P. Hackenbush trilogy for Brainstorm, compiled in book form in 1982, to his many gigs on major characters at 2000AD and DC.

A major turning point in his art and storytelling came in 1997 with The Tale Of One Bad Rat from Dark Horse. His drawings took on a greater sophistication, as sharp, clear-line images based on his photographic references of friends-turned-models became key to creating compellingly believable characters, while his newly vivid, subtle palette brings their worlds to colourful life. In his layouts, compositions, dialogues and narrative techniques, his creativity reached new highs. What he began as a life story of children’s book illustrator Beatrix Potter he deepens into a rich, affecting drama about her modern namesake Helen Potter, a young victim of parental abuse, who runs away from home with a rescued lab rat. Living on the streets of London, she can’t erase her father’s leering face from her dreams or her relationships. To escape, she traces Beatrix Potter’s steps to the Lake District, where she finds some security and the strength to confront her father face-to-face. This book is all the more powerful for not offering easy answers and finding some cause for hope in an allegory in the form of the expertly executed ‘missing’ Beatrix Potter tale of the book’s title. Lessons learnt here were then applied on his 1999 ‘sequel’ to Arkwright in the ornate, grotesque Victorian ebullience of Heart Of Empire, again from Dark Horse.

Making the jump from one British genius of children’s fiction to another, from Beatrix Potter to Lewis Carroll, from Helen and her rat to Alice and that white rabbit, has resulted in a further leap in Bryan’s artistry, experimentation and sheer scale. Clocking in at a weighty 318 full-colour pages in hardback with matte gold blocking on the title, Alice In Sunderland is "one big comic" alright. Despite its droll title, Alice In Sunderland is not some slight cartoon parody of Lewis Carroll’s famous tale. Among other things, it is a fresh retelling in the graphic novel form of the surprisingly interwoven stories of Carroll and his young muse, and of the city of Sunderland.

Shortly after the Wigan-born comics artist Bryan Talbot moved there, he became intrigued by the researches of local historian Michael Bute into Sunderland’s links with Carroll - links which in Bute’s and Talbot’s view have been overshadowed by Oxford’s claim on him. Equally intriguing are the area’s close connections to the real Alice and her family, the Liddells. The more Talbot enquired, buoyed by Bute’s further discoveries, the more complex and compelling his tapestry became.

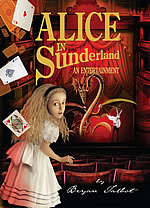

Shrewdly, Talbot avoids turning this minefield of information into a worthy “educational” comic. Instead, he subtitles the book “an entertainment” and delivers this by structuring it as a highly theatrical performance on paper. On the front cover we follow a wide-eyed Alice into the plush, deep-red auditorium of the Sunderland Empire. Turning inside, we find a safety curtain fills both endpapers, ready to rise, while on the title page a weathered playbill trumpets the variety show to come. The whole production unfolds, freewheeling and wide-ranging, across 318 colour pages, with an intermission, a visit backstage, two finales and “numerous diversions and digressions”.

The three principal actors are all personifications of Talbot. First in order of appearance, from Talbot’s rough sketch through pencilled composition to finished drawing, is The Plebeian - plump, unshaven, surly, in leather jacket and jeans, impossible to impress, typical of the Empire’s tough audience. Next, stepping through the curtain in a rabbit mask, is The Performer, an ageing classical actor in billowing white shirt, self-important, hammy, uptight. He is our master of ceremonies and joint narrator, mainly stage-bound but able to adopt assorted disguises such as Woody Allen, Sherlock Holmes or Groucho Marx.

The third cast member is The Pilgrim, or the writer-artist Bryan Talbot, creating the book we are reading and playing its other narrator. He is more free to stroll around Sunderland, once the world’s biggest shipbuilding port, and far and wide through our past and present, meeting people real and imaginary from Her Majesty the Queen and George Formby to the Mad Hatter.

The comics medium seems ideally suited to this project of presenting both the passage and simultaneity of time. Unlike the flickerings of film, comics can fix panel after panel of different moments to be read, re-read and related to each other. Apply this to a whole book, and you have a way to convey these various interrelated histories as they ebb and flow through time.

On many pages, Talbot also experiments with a different, less rigid approach to the usual grids of panels. Building on traditional collage, he takes full advantage of the hi-tech options of digital cameras and Photoshop software to merge images, objects, maps, into a kaleidoscopic stream, giving his photographs a watercoloured softness.

These multi-layered fantasias serve as backdrops and sets for Talbot’s three alter egos, and other characters whom he depicts in crisp black-and-white lines, with occasional grey tones. In this way, they stand out on the same plane as the black lettering in their white speech balloons and commentary captions. Meanwhile, to distinguish Carroll, the Liddells and other figures and artefacts of the period he tends to apply sepia or pale blue washes.

Well aware that his mission to explain needs to be kept entertaining, Talbot seeks to instil a healthy scepticism in the reader by making the Performer brandish a sealed envelope in which one “complete whopper” of a falsehood is kept, only to be disclosed at the end. Talbot is also aware that his narrators’ sometimes dense monologues risk seeming like lessons, so he cleverly undercuts them with outbursts by the grouchy Plebeian, by the ghost of the late Carry On comedian Sid James - who literally died on the Sunderland Empire’s stage and is said to haunt it still - or at one point by the “real” Talbot, waking from a nightmare, plagued by doubt.

Other “diversions and digressions” tap into the evocative stylings of our comics and graphics heritage: a Tintin-style Moroccan interlude; the battle speech from Shakespeare’s Henry V spoofed in Mad magazine’s ‘jugular vein’; a Fifties American horror comic about a ghost story; a meticulously engraved retelling of “Jabberwocky”; the Battle of Hastings given a Marvel Comics makeover; The Legend of the Lambton Worm, part William Morris, part Alien; a critique of current anti-refugee hate-mongering on a torn-off lined notepad; a visitation by Scott McComics-Expert alias Scott McCloud; a Boy’s Own account of brave Jack Crawford: even a page scripted by Beano legend Leo Baxendale. These form part of an underlying theme celebrating the alchemy of words and pictures, from the Bayeux tapestry and Hogarth’s prints to Sunderland’s sculpture trail. And to the timeless Alice books, the first illustrated by Lewis Carroll himself.

Alice In Sunderland is a tour de force landmark in graphic literature. The book’s subjects expand and as more patterns and connections form, the reader’s imagination expands with them, until, like the dissolving borders between panels, like the stunned Bryan at the end of the book, we are awoken to the Wonderland that surrounds us everyday. Its cumulative effect, each scene leading to the next while linking back, feels mind-expanding. This comes home in his first downbeat ending, where Talbot, sketching urgently on to a torn-off notepad, converges multiple references planted in our heads into an eloquent indictment of anti-refugee hate-mongering. Then the curtain has hardly fallen before a second ending unravels and everything converges again. As the “real” Bryan Talbot stirs as if from a dream in the Empire theatre, the same climax awakens the reader to the continuity and connectedness of all our lives.

Meanwhile, Alice’s other reincarnations in comics grow ‘curioser and curioser’, none more so than the ongoing Alice Experiment by avant- garde Franco-Belgian collective Frémok. Frémok have also reissued Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, the version of Alice which was hand-written and illustrated with 37 drawings by Carroll himself and given as a Christmas gift to Alice Liddell on November 26 1864. That his Alice lives on today in comics and graphic novels would no doubt please Carroll immensely. Bryan Talbot remarks on Carroll’s pleasure in comics and cartooning, pointing out that he owned a copy of Rodolphe Töpffer’s landmark 1840 proto-graphic novel The Adventures Of Obadiah Oldbuck, and he was a keen reader of Ally Sloper, Britain’s great Victorian strip hero, in Judy magazine, to which he tried unsuccessfully submitting his writings. So the thoughts Carroll gave Alice in the book’s opening paragraph - "What is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?" - could very well be his own.

THE BRYAN TALBOT INTERVIEW

The following interview with Bryan Talbot was conducted by Paul Gravett Interview on November 11th 2007 by email for The Comics Journal.

Paul Gravett:

In your researches, did you discover more secrets and links than you could fit into Alice In Sunderland’s 300-plus pages? And have any new revelations come to light since?

Bryan Talbot:

There were quite a few interesting nuggets that I had to discard purely because I couldn’t fit them into the structure of the book without them seeming forced. The faux stream-of-consciousness style that I used for a lot of the book has to flow extremely smoothly to work. The structure of the book has to be rock solid. If I’d tried to crowbar them in, they’d have stuck out like sore thumbs. Still, I managed to get in all the important elements and nothing major has emerged since.

How would you explain the crossover success of Alice In Sunderland? How much of it builds on Alice’s fame and people’s abiding fascination with Carroll’s stories?

Quite a lot, I’d have thought. Alice is a phenomenon, totally pervading our culture. Whether people know it or not, they’re quoting Lewis Carroll almost every day of their lives. His words, like Shakespeare’s, are so much part of our language. The book also seems to be being read by people with no knowledge or interest in Alice, which is encouraging. The fact that the book is non-genre makes it appeal to a wider audience.

How much of it also helps that literary publisher Jonathan Cape are publishing it? How have they been to work with?

Having Cape publish it has had a huge effect in the UK. The mainstream press has treated it as a “proper book” instead of a comic. If it had been published by a comic publisher I’ve no doubt that it would have been ignored. As it is, it’s had large and extremely positive reviews in all the quality UK newspapers and I’ve been interview on local and national radio and TV. This has resulted in great sales figures, with the book just going to it’s third reprint since April. In the US, it’s published by Dark Horse Comics, so hasn’t had this literary seal of approval and consequently hasn’t been reviewed (as far as I know) by the mainstream media.

It’s been a joy working with Cape. They are super efficient at PR and seem to have done everything possible to bring the book to people’s attention since it was published.

What has the reception been like to the book in your home town of Sunderland? Are you now a local superstar celebrity?

The local newspapers have gone crazy over it. I’ve lost track of the number of articles that have appeared. Seems like there’s been one about every two weeks since it was published. It was the cover feature on most local culture mags. One bookstore in the city has sold over 500 copies and expects to sell the same amount again over Xmas. Still, I don’t think I’ve become a “superstar”! I can still walk down the street without being recognised! The book’s inspired quite a bit of “Alice tourism”. I keep hearing of people coming to the town (even from as far away as the States) to visit the locations. I’ve actually been made an official ambassador of Sunderland by the city council!

How did the experts at the Lewis Carroll Society of North America react to your propositions and especially reevaluating the significance of Sunderland on Carroll’s life and oeuvre?

The presentation I did for them at their annual meeting at Columbia University on the seventy-fifth anniversary of Alice Liddell’s visit there was extremely well-received and the members very flattering about the talk - even in their blogs about the event. I was a bit intimidated just being there at first but they were all very welcoming and many said they loved the book. I did the talk again to the British Lewis Carroll Society a month later and had a great reception there too.

Am I right that Alice could never have been produced in its present multi-faceted form without PhotoShop - what do you see as the pros and cons of this software on your writing and drawing?

This is the first book I’ve produced that’s composed on computer, though the drawings were done traditionally with pen, brush and ink before being scanned in. Quite a few of the images had a multitude of layers and the collages had as many as two hundred. They couldn’t have been produced any other way. Some of the line drawings were placed on old, yellowing paper, or even parchment in one sequence, photographs were run through various filters and images were blended together in a way that would have been impossible in traditional collage.

How would you answer any comics purists uncomfortable with the predominant collage approach of Alice’s more didactic sections, whereby you eschew panel borders and prefer images to blend and bleed into each other and off the edges of the page?

I’d tell them that Alice IS pure comics. It uses all of the toolbox and couldn’t have been done in any other medium. I first used collage nearly thirty years ago in a lengthy sequence in The Adventures Of Luther Arkwright, something inspired by Jack Kirby’s innovative use of it in the 60s. And drawn metapanels - panels dealing with multiple images - have a long and honourable history.

Might Alice In Sunderland work as well as an interlinked website? What does the graphic novel format do that a website can’t?

An interlinked website wouldn’t work as a story. If there’s anything at all that’s clever about this book it’s the structure hidden beneath the surface. It shouldn’t be obvious to the reader but the order that the information is presented in is crucially important. It holds everything together. Clicking on things at random wouldn’t produce a cohesive narrative, just a series of uncoordinated pieces. For anyone who has an attention longer than that of a gnat, it would be very unsatisfactory. Besides, the book is a nice artifact to hold in your hand. I wanted it to be a weighty and sumptious tome.

As if to avoid seeming too serious and literary, you’re also putting out two other new books that display your much wilder, wackier humorous side that goes back to your underground and satirical roots. First there are your squirm-inducingly scandalous exposés about comics creators in The Naked Artist. How much did you censor yourself? Have you had any complaints or threats of lawsuits yet?

None… yet. I do use the word “allegedly” quite a lot! Most people seem happy to be in there, revel in it, in fact. As Oscar Wilde said, there’s only one thing worse than being talked about and that’s not being talked about. Anyhow, it’s simply a fun book. It’s not “Comics Babylon” - it doesn’t dish dirt, it just tells funny stories. Many people have told me that it’s made them cry with laughter. I deliberately avoided telling tales of extra-marital affairs, serious criminal activity or outright nasty behaviour. I could have told much worse stories about some people - and they know it. Anyway, they can’t really complain - I take the piss out of myself more than anyone else.

After about four years of working on Alice it was sweet relief to quickly bang out a book of funny prose - it was hugely enjoyable to write.

The other new book is Cherubs! with you writing and laying out pages for the brilliant, underappreciated Brit artist Mark Stafford. What’s the premise and goal behind this irreverent ‘divine comedy’?

Yeah, Mark’s the hottest Brit indy artist and he’s done a staggeringly great job. His stuff really rocks. I’ve just received a PDF of the finished graphic novel and it looks incredible. Cherubs! is an irreverent fast-paced supernatural comedy-adventure. It concerns a gang of five cherubim who are put in the frame for the first murder in heaven and escape to New York on the eve of the apocalypse. Pursued by two terminator-like seraphim enforcers they encounter a vampire hoard, fairy hookers, renegade archangels and an “exotic dancer” named Mary. It’s exciting and funny and cool.

You told me your wife Mary has a new job in Nottingham so you plan to relocate there. Any plans to explore the city’s legendary figure Robin Hood in graphic novel form?

I already had some books on him. Don’t think I’d like to do a straight version of the legend but, if I do something, I may come at it from left field, as I did with Alice. I’ve already started watching DVDs of the 1950s British TV serial staring Richard Greene. It’s very interesting as it was written by American writers blacklisted by McCarthyism.

Following Cape’s success with Alice, what are you lining up with them next? Are Cape now committed to you as an author?

They seem to be. They’ve been very impressed by the performance of Alice. Next spring they’re publishing a British edition of The Tale Of One Bad Rat as the first in their new series “Classic British Graphic Novels”. They’ll also be publishing the graphic novel that I’m working on now - a detective steampunk thriller entitled Grandville [due for release in spring 2009].

You have done so much to unlock the potential of the graphic novel, but what still remains to be unlocked now?

If I knew that, I’d be psychic.

Any latest news on Alice?

It’s now in it’s 3rd printing and UK sales have passed 10,000. In November the first foreign edition was published in Italy, with 3 more countries publishing it in 2008.

PG TIPS EXTRA

The Art of Bryan Talbot

by Bryan Talbot

NBM $19.95

“When it comes to art, I usually claim that I’m self-taught. That is to say, I was taught by a very ignorant person indeed.” From his first words, Bryan sets the witty, self-effacing tone of his commentary that accompanies an impressive scrapbook of his ongoing artistic maturation. Not well served by his art teachers at grammar school or art college, he learnt how to draw only by studying for himself from library books. “I finally began to learn about the fundamental principles of drawing. I’m learning them still.” To me this is one of Bryan’s greatest strengths, his tireless eagerness to evolve, to improve, to experiment with different styles, media, subjects.

Here he goes right back to some of his very earliest childhood comics made when he was only ten, like ‘Fred Kelly in Bricks Are Forever’. He also shows some of his first forays into fanzines which led to the breakthrough in Brainstorm Comix (1975-78), a stand-out anthology from the British underground published by Lee Harris’s Alchemy. Unpublished treats include a previously unpublished painting from 1975 called The Hermit, set inside an ornate Victorian frame, and a ‘G-Man’ cover co-created with Pat Mills for the aborted comic magazine Heroes, intended by Egmont in 1986 as a rival to 2000AD (Mills & Talbot completed a six-page pilot episode). Zappa, Hendrix and Adam Ant feature in his rock art portfolio, while Luther Arkwright, Dan Dare, Judge Dredd and Nemesis represent the British comics icons. To improve his drawing still further, Bryan took life drawing classes from 1988 to 1993 and includes 12 pages of fine nude figurework. Rare posters, cover and card art, frontispiece illos and private commissions are mixed with highlights from his graphic novel and comic book career, right through to a teaser portrait of badger detective LeBrock from the forthcoming Grandville.

Let down only by slightly thin card covers, this glossy 96-page paperback offers sharp reproduction and generous oversized presentation, an intro by collaborator Neil Gaiman and a 3-page stripography. Bryan’s constant evolution is inspiring proof that with dedication and application you can teach yourself and never stop learning.

Sarah Blaireau from Grandville

The main article above first appeared in Comics International and is represented here with Paul’s review of Alice In Sunderland first published in April 2007 in The Independent newspaper. The short interview with Bryan Talbot first appeared in The Comics Journal.