British Comic Creators:

The Heroes Of UK Comics

I don’t intend to get too flag-wavingly patriotic here, but it has to be said that British comics creators stand amongst the greatest in the world, whether in those favourite anarchic weeklies from childhood or the most bleeding-edge adults-only graphic novels. It’s tough to choose but here’s my shortlist of the ten of the most interesting innovators alive today who have transformed the UK and international scenes.

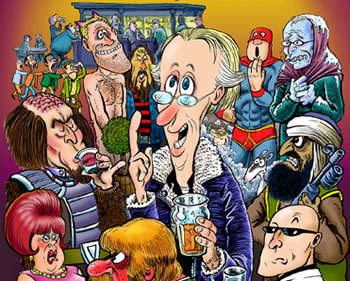

LEO BAXENDALE

"THWACK!" "AAAAAArrrrggghhh!" "THROB!"

This solid, soft-spoken, Lancashire-born genius, who injected some of wildest, most surreal, "Gooni-sh" buffoonery into The Beano, would have become a celebrated national treasure, if not for the fact that his Dundee-based publishers D.C. Thomson didn’t allow him, or hardly anyone, to sign their comics. But ever since 1953, Leo Baxendale’s beloved, unstoppable kid characters have warped generations of young Brits raised on role models like Little Plum, Your Redskin Chum, Minnie the Minx and Danny, Sidney, Herbert, Wilfrid, Smiffy, tomboy Toots, Fatty and Plug ("He was so damned ugly, but no matter how gormless he looks, he’s always blissfully content."), otherwise known as The Bash Street Kids. "I’m congenitally incapable of drawing two characters just talking to each other. So if Teacher was telling the schoolkids something in class, they wouldn’t just sit listening, they’d be cutting Teacher’s tie off or pouring treacle or ants inside his trousers." Hemmed in by Thomson’s moralising conventions and tight deadlines and page rates, Baxendale jumped ship to London competitors Odhams where he helmed a slicker ‘Super-Beano’ called Wham! between 1962 and 1964. This was home to such hits as Eagle-Eye Junior Spy and his macabre arch nemesis, Grimly Feendish, which finally bore his signature. In 1975, after 22 years of weekly deadlines, Baxendale quit the treadmill to invent his own pint-sized protagonist, Willy the Kid, star of three timelessly lunatic hardback annuals. He tried standing up to Thomsons and suing for the copyright to his Beano characters, but on legal aid he was forced to settle out of court, the money enabling him to found his own publishing company, Reaper Books. Long retired from drawing and 80 next year, Baxendale and his multiple styles live on in many of today’s funnies for children, in Steve Bell’s Guardian strip If and Savage Pencil’s deranged scrawlings, and in those millions of adults who as youngsters lapped up his uninhibited wackiness.

HUNT EMERSON

Cross-breed George ‘Krazy Kat’ Herriman with Robert ‘Fritz the Cat’ Crumb and you wind up with one of the zaniest adult comix artists in the country, if not the world. Hunt Emerson broke out of the 1970s Birmingham alternative arts scene with a litter of his own funny felines, sex-mad Firkin for Fiesta and frazzled Calculus Cat for Escape. His penchant for comedy timing and elasticated brushstrokes perfectly suits graphic novelisations of Lady Chatterly’s Lover, The Life of Casanova, even The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Hunt’s in purgatory right now, toiling on Dante’s Inferno, a very different version from those by Botticelli, Doré or Tom Phillips. "I’ve added a few modern references like mobile phones, but it’s not a satire. Dante and Virgil chat and squabble, while sinners, demons and monsters all seem to be getting on with their lives (or eternities). There’s a fair degree of slapstick, and some great opportunities for spectacular, ‘Crazy, man’ drawings." That triple-headed pooch Cerberus has never looked more insane or disturbing!

NEIL GAIMAN

Neil Gaiman portrait by P. Craig Russell

If all he’d ever done was start virtually from scratch with the all-but-forgotten 1940s DC superhero, Sandman, and dream up an allusive, elusive modern mythology hailed by Stephen King and Tori Amos, Neil Gaiman would qualify here. But he’s done so much more, in comics as well as award-winning fiction. He had the knack right from the start, as he and artist Dave McKean fused their skills in their milestone debut Violent Cases about faulty memory, fatherly abuse and Al Capone’s osteopath. As well as their further graphic novels and children’s books, Gaiman’s also surprised with his riffs on superheroes, fabricating 17th century incarnations of the Marvel Universe in 1602 and reviving Jack Kirby’s space-gods The Eternals. Then there are the movies, from his original scripts and others based on his works, from the CGI-animations Mirrormask and Beowulf to Stardust and now Coraline, released in the UK in May. "Stardust was all about compression, squishing a 10-hour story down to a 2-hour film and getting the same emotional effect. With Coraline, even though it takes three hours to read, so much is just her walking around and what’s going on in her head, that when you squish it down, it’s maybe a 50-minute movie. So Henry Selick, who made Nightmare Before Christmas from a Tim Burton outline, is adding stuff to make it a bigger. Henry also did James & The Giant Peach. Coraline has that atmosphere but it’s its own thing. It’s going to be very cool."

MELINDA GEBBIE

Her husband Alan Moore introduced her into his novel Voice Of The Fire as an "underground cartoonist late of Sausalito, California; former bondage model turned quarkweight boxer." Melinda Gebbie flowered as an artist and writer during the San Francisco Seventies hippy comix explosion in Young Lust, Wimmen’s Comix, Wet Satin and her surreal 1977 solo Fresca Zizis (Italian for "fresh cocks"). Eight years later, mere months after moving to the UK, Fresca Zizis was seized in a vice raid and Gebbie was hauled up before a judge on obscenity charges to defend "depicting three women astride a giant green penis. His verdict was that all the comics should be confiscated and destroyed. They burned all 400 copies of my comic and made them illegal to possess in Britain." Luckily the same fate has not befallen Lost Girls, her three-volume porno-graphic novel, sixteen years in the making with Moore, in which they imagine the erotic destinies of children’s book heroines Alice, Wendy and Dorothy. Here, Gebbie’s exquisite hand-painted artistry shines referencing classic erotica from Schiele to Beardsley. "We just liked the idea of making everything as intricately sexual as possible, even the finest details. We were really influenced by things like the Yellow Book, by the grand old periods of illustration where there were beautiful designs on every page." A $45 single-volume hardcover of Lost Girls comes out in April.

BRENDAN McCARTHY

We live in the pop culture age of McCarthy-ism. This virtuoso London visionary has designed pop videos for Michael Jackson and Def Leppard, movies like Coneheads and Sweeny Todd, kids’ TV classics like Jim Henson’s The Storyteller and Reboot, and loads of stunning, signature comics, including Morrison’s Zenith and with writer-friend Peter Milligan the Indian psychedelia Rogan Josh and the controversial Thalidomide skinhead exposé Skin. Home from Hollywood after co-writing and designing a new Mad Max movie, so far unmade, McCarthy has been hired by Marvel to craft a Spider-Man and Doctor Strange team-up, Fever, out in three parts this summer by the Marvel Knights imprint. It’s his tribute to the fantastic Sixties weirdness of artist and co-creator Steve Ditko. "I can never hope to match the astonishing beauty and oddness of Ditko’s visual style, but to pay homage and have a lot of fun was the basic idea! I’m a bit bored with the ‘hard edged’ vibe prevalent in the industry, so I prefer to create a comic that owes more to The Wizard of Oz, Yellow Submarine and The Mighty Boosh, a comic that’s a bit different." By the Hoary Hosts of Hoggoth, Spidey and Strange will have never looked stranger!

PAT MILLS

Marshal Law created by Pat Mills & Kevin O’Neill

Prolific, provocative and above all passionate, writer and editor Pat Mills has been hailed as "the godfather of British comics" for essentially rescuing the industry from the brink of extinction in the Seventies by developing three unforgettable, mould-shattering titles. Remember the terrifying trench warfare of Charley’s War, the shark-attack bloodbaths of Hookjaw, the Celtic warrior’s "warp spasms" in Sláine? Behind these and more is writer and editor Mills whose anarchic, anti-authoritarian bite kickstarted Battle (1975), Action (1976) and 2000AD (1977), "The Galaxy’s Greatest Comic". Here, as well as writing Judge Dredd, ABC Warriors and Sláine, Mills teamed with Kevin O’Neill on Nemesis the Warlock, a horned, hooved, demonic-looking alien, who was the ‘hero’ battling human bigotry on a galactic scale. Later for Marvel’s Epic line they collaborated on Marshal Law, a bitter, brutal superhero-hunter wrapped in leather and barbed wire, now in development as a movie. Branching out into France’s lavish fantasy bande dessinée field and a screenplay for his upcoming graphic novel American Reaper, this is one "dark, Satanic Mills" who is still buzzing with over-the-top concepts.

ALAN MOORE

Alan Moore portrait by John Coulthart

Beneath those unfeasibly florid, Rasputin-like locks lies the seething brain of one the world’s most remarkable writers and thinkers, and not solely within the pages of comics. Every genre and cliché he touches, he revolutionises and reinvigorates, whether garish musclebound superheroes in Miracleman, Watchmen and Tom Strong or Jack the Ripper theories in From Hell, an Orwellian fascist future-Britain in V for Vendetta or Victorian fantasy figures in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. The rumour has arisen that Alan Moore is some sort of odd recluse who never leaves his modest-looking (at least from outside) terraced home. Far from it, as he’s become a familiar, low-key legend on the streets of his native Northampton, garbed all in black, huge ornate rings on every finger, and he certainly does travel forth for public appearances and the occasional ‘workings’ or magical performances. That said, he hasn’t renewed his passport in years. Why bother when his most vital journeys these days are interior ones, into the realms of storytelling and ideas? As he told me, "If I did get a passport, I’d wish to be described in it as a ‘magician’, because that seems to cover writer, actor, singer, all those things I do that use words, representations, sounds, drawings, everything."

A bright working-class lad born with no useful sight in his left eye, and no hearing in his right ear, ("At least I’m balanced"), Alan was expelled from school for dealing LSD. Without qualifications or references the teenager was reduced to cleaning toilets and skinning sheep. And there his career might have ended, had it not been for his getting involved in writing and performing within Northampton’s Arts Lab counterculture and then trying his hand at humour comics, at first for the local press but soon for rock paper Sounds. Married with a child on the way, he switched from drawing - "I was slow and not very good" - to focus on scripts for others to draw, breaking into SF weeklies Doctor Who and 2000AD followed by "weird heroes" monthly Warrior. These brought him to the attention of major American publishers DC Comics who assigned him their poor-selling, man-turned-bog-monster series. In one issue, Moore turned the hoary concept on its head, revealing that Swamp Thing could never revert to his former self, because he was actually a form of plant-life dreaming of being human. It was the start of Moore’s meteoric reimagining of American mainstream comic books. "I found that collaboration is one of my big talents. I believe that looking at an artist’s work and understanding it correctly reveals a lot about them. I understand their sense of humour, what excites them, intellectually, visually, what their influences are." This skill continually brings out the best in every artist he works with.

A man of strong principles, Moore has stood firm against the exploitations and idiocies of the corporate comics industry, part shark, part dinosaur. He’s also spoken out against Hollywood’s adaptations of his stories, the majority mediocre. After the travesty of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Moore and artist Kevin O’Neill vetoed a proposed sequel and took the series they co-own from DC Comics to creator-friendly independents Top Shelf (US) and Knockabout (UK). This year they unleash an astonishing LXG trilogy, Century, whose sheer scope and daring outshine anything that a mere movie could hope for. When it comes to Zack Snyder’s Watchmen blockbuster, a graphic novel deemed "unfilmable" by first director Terry Gilliam, Moore explains, "I put a curse on the whole thing." And in no time, 20th Century Fox were suing Warner Brothers for the property and until late January jeopardising its March release. Moore is working his magic for other purposes too, starring in his own one-man documentary movie, The Mindscape of Alan Moore (out on DVD from Shadowsnake Films), writing a second prose novel, Jerusalem, set again in his home town, and with close friend Steve Moore (no relation) devising The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, promising "a clear and practical grimoire of the occult sciences." Moore has mastered that greatest trick, the magic behind all creativity, making something out of nothing.

GRANT MORRISON

"I like the irony of being able to explore or present sophisticated philosophical notions in the pages of a trashy superhero comic." Brimming with attitude, this shaven-headed, troublemaking virtuoso scribe has come along way from his Glasgow punk roots and presumptuous teen debut Gideon Stargrave in 1978. He’s not stopped radically re-mythologising superheroic clichés, from deconstructing them in 2000AD‘s swaggering brat Zenith and obscure DC oddities Doom Patrol and Animal Man to finding the primal appeal of mega-sellers X-Men, Superman and Batman. "Bruce Wayne is a very compelling fantasy figure. Super-rich, handsome, dynamic, troubled. The horns give him a hint of the devilish but his soul is spotless. He’s a proper Gothic hero: a romantic, Byronic figure that kicks ass." Equally thrilling and challenging are the ambitious series he’s conceived himself like the freedom-fighting occultists The Invisibles and the sad, beautiful We3, a dog, a cat and a rabbit transformed by the military into killer cyborgs. Morrison has written the screenplay for this one and Kung Fu Panda‘s John Stevenson is set to direct.

POSY SIMMONDS

Don’t be fooled by Posy’s demure appearance and plummy voice. Her powers of observation are laser-sharp, her mimicry of accents and types cruelly precise. For years, hardly anybody outside of Britain had heard of Posy Simmonds unless they read her weekly Guardian social satires or the occasional book collections. But all that’s changed with the tragic leading beauties of her very English murder-mystery graphic novels, Gemma Bovery and Tamara Drewe, widely translated and internationally acclaimed. "Gemma’s dream was to live this rustic, simple life in France and somehow the very goodness of it would rub off on her and she’d be fulfilled. And of course she gets as bored as anything because life isn’t like that and Normandy is the piss-pot of France. So she has adventures, particularly with a young French aristocrat who is also fairly dim and shallow but has his own romantic thing about him." Complicating her life further is a secret, infatuated local who is convinced that Gemma will come to the same sad end as her namesake, Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Tamara fares little better after turning an English village’s surface calm into a maelstorm of passions. Riddled with class clashes and repressed desires, her comics are quintessentially English.

BRYAN TALBOT

Bryan Talbot portrait by Hunt Emerson

He’s drawn Batman Sandman, Dredd and Nemesis and come up with some unconventional leading men of his own, from Brainstorm Comix acid-tripper Chester P. Hackenbush to saviour of parallel worlds Luther Arkwright, but Bryan Talbot’s latest hero, Inspector LeBrock, is "a large working-class badger with the deductive abilities of Sherlock Holmes but also a bruiser who’s quite happy to beat the crap out of a suspect to get information." Taking his title, Grandville, from the nom-de-plume of the 19th century artist who satirised French society by morphing animals into humans sporting the latest fashions, Bryan describes his forthcoming graphic novel as "a steampunk detective thriller set in an anthropomorphic fin-de-siecle Paris. It starts with LeBrock investigating a murder in a small English village, which is actually Nutwood from Rupert Bear. The trail leads him to Grandville, where he unearths a shocking, far-reaching conspiracy." It’s a high-octane romp jammed with delicious details and another real tour-de-force alongside his acclaimed reimaginings of Beatrix Potter in Tale of One Bad Rat and Lewis Carroll in Alice in Sunderland.

Posted: February 15, 2009This article first appeared in the March 2009 issue of Bizarre magazine.