Best Comics of 2017: An International Perspective Part 2:

Year in Review

You know, there’s an awfully big world of comics out there! And it’s that time again to invite my International Correspondents, connoisseurs across the planet - Heitor Pitombo, Matthias Wivel, Harri Römpötti, Gert Meesters, Matteo Stefanelli, Pedro Moura and Michał Chudoliński - to recommend to you their favourite comics and graphic novels created and (in most cases) also published in each country they know well during last year. This annual International Perspective remains vital in my view to broaden our knowledge and appreciation of the diversity of this truly global medium.

BRAZIL - DENMARK - FINLAND - FLANDERS - ITALY - POLAND - PORTUGAL - SPAIN - THE NETHERLANDS

Brazil

Selected by Heitor Pitombo

Heitor Pitombo began his career in Brazilian comics in 1990 writing articles for the Carioca newspaper Tribuna da Imprensa. In the following year he was a member of the Rio de Janeiro International Comics Biennale’s staff, the first major Brazilian event of its kind. From 1992 on, he began a long association with the Brazilian Mad magazine as assistant editor and then a Portuguese translator, and started writing for most of the country’s specialist comics magazines. In 1998 he won the HQ Mix award for The Universe of Super Heroes, the first Brazilian CD-ROM about comics. As a translator, he wrote Portuguese versions of comics originally produced by Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, John Byrne, Garth Ennis and several others. He wrote two books about comics: 300 Mangas and Endless Beings: The Oneiric Universe of Neil Gaiman. A third book is on its way. Right now he’s a member of Mundo dos Super-Heróis’s (World of Super Heroes) staff, the most important publication about comics in the country.

Angola Janga - Uma História de Palmares (‘Little Angola - A History of Palmares’)

by Marcelo D’Salete

Veneta

Marcelo D’Salete has just won a 2018 Eisner Award for the Best U.S. edition of international material with the English translation of his 2014 book Cumbe (‘Run For It’) from Fantagraphics. But his latest major work published in Brazil is by far his greatest achievement up till now. In its 432 pages, Angola Janga tells the story of the rise and fall of Palmares, the biggest quilombo ever assembled in Brazil’s history. For those who don’t know, quilombos were settlements founded mostly by escaped slaves of African origin, which came into existence when they arrived in colonial Brazil around the 1530s. Palmares developed from 1605 until 1694, when it faced suppression by the Portuguese settlers. The fact is that the quilombos were starting to grow in size and importance and were turning into somewhat of a threat – also the Portuguese wanted “their slaves” back. Palmares had two larger consolidated entities (“Great Palmares” and “Little Palmares”), each with a large fortified central town that held 5,000-6,000 people, and was surrounded by valleys filled with many mocambos or refuges for slaves in the woods. Since 1654, the Portuguese had been organising expeditions against Palmares and in 1694 they made their final attack and captured their leader Zumbi, who was beheaded the following year.

Angola Janga is definitely the most incisive story in comics written about this theme, as it demystifies certain “historical convictions”. Although Palmares was a great entity with several major settlements and many smaller ones, at a certain point in time it was not considered an isolated territory in colonial Brazil. The quilombos were spread out all over the colony and in someway a part of its landscape. The changes in this relationship are not only due to the need for more slaves, but also deeply connected with the growing tensions related to the origins of racial prejudice in this country. Apart from its literary content, very rich in itself, this comic portrays a very intelligent use of sequential art. Each frame is magnificent on its own and sometimes the reader doesn’t need a huge amount of text to understand what’s happening.

Couro de Gato - Uma História do Samba (‘Cat Leather - A Samba Story’)

Couro de Gato - Uma História do Samba (‘Cat Leather - A Samba Story’)

by Carlos Patati & João Sanchez

Veneta

The late Carlos Patati (1960-2018) had a long career as a comic writer, and was the first Brazilian correspondent for this website. His legacy for Brazilian comics will be remembered for years to come and by all who got in touch with his expertise at conveying all sorts of themes, most of them unusual in the comics form. His last work in life was no exception. Here, Patati uses real and imaginary characters to recall the origins of Samba, Brazil’s most typical style of music. João Sanchez’s superb art embellishes this book using a style very reminiscent of the 19th century in this country: xylography or wood engraving. In the first chapters of Couro de Gato, Sanchez actually engraved his art onto wood, but due to deadlines, he opted to work on the rest of the book using a process Patati called “xyloderivative”, in which he tries to maintain wood engraving’s distinguishing marks in search of an original format. The title of the book, ‘Cat Leather’, alludes to the skin of cats, reputed as being the material (along with the metal frame) used to make the Brazilian tamborim drum in those days, one of the main instruments used to play Samba. The plot goes back in time to the end of the 1800s, up to the beginnings of the 1900s, in Rio de Janeiro, to evoke Samba legends such as Donga, Sinhô, Pixinguinha, Noel Rosa, Ismael Silva and Cartola – all of them notable Brazilian composers and musicians of the genre. This work suits the writer’s talent very well. After all, one of Patati’s main virtues had nothing to do with outlining great narratives, but was about contemplating their backgrounds, expressing very well the atmosphere of the periods he chose to portray.

Já Era (‘It’s Gone’)

by Felipe Parucci

Lote 42

Felipe Parucci has already displayed his talent in his first major work Apocalipse, Por Favor (Apocalypse, Please, 2015). The good thing is that his latest book, Já Era, reaches the same standards his previous graphic novel achieved. Using his very personal style, Parucci works with a mix of social criticism, interplanetary voyages, language codes and all kinds of gags available to poke at consumerist society. Já Era tells the story of Regina, an advertising woman who gets fed up with her work and quits her job. Soon her cellphone is stolen and she decides to buy a sailing boat in order to begin what’s supposed to be a long trip adrift. It’s when she’s in the middle of the sea that she gets abducted by a spaceship that takes her to an unknown planet. The directions Parucci’s tale sends the reader are completely unpredictable. More than that, he plots a tale that never gets lost in more than 300 pages, partially due to his pencil work that seduces the eyes and improves the storytelling. Felipe uses the variation of blacks and whites to emphasise passages of time and displays silent panels in the most clever way. Amazing virtues for a guy who has just published his second major work.

Olimpo Tropical (‘Tropical Olympus’)

by André Diniz & Laudo Ferreira

Jupati/Marsupial

André and Laudo are two of the greatest Brazilian comics artists of today. Separately, both have built tremendous careers over the last 30 years. Together they’re unbeatable. Although they live in different countries – Laudo is still a resident in his native São Paulo, while Diniz is trying to establish an international career living in Lisbon since 2016 – the two of them managed to work on a major project together for the first time. Inspired by an earlier book written and pencilled by Diniz (Picture a Favela, 2012, in English from SelfMadeHero), Olimpo Tropical spies on the universe of drug trading in a favela in Rio de Janeiro and it never lets the reader down. The life of Biúca, the story’s main character, is unveiled in a plot that’s common to several other youngsters from similar places, both in what’s glorious and in what’s disastrous. Whilst André‘s plot is accurate and doesn’t have discrepancies, Ferreira’s art is dynamic and makes the story more captivating. Sometimes, physical distance makes no difference.

Denmark

Selected by Matthias Wivel

Matthias Wivel is Curator of Sixteenth-Century Italian Paintings at the National Gallery, London. He has written about comics widely for about twenty years.

Fiesta-Magasinet (‘Fiesta Magazine’)

by various authors

Fiesta-forlaget

Last year, a trio of veterans of the Danish comics scene, Mårdøn Smet, Peter Kielland and Johan F. Krarup, revived the kind of comic book concept in which they made their names: the saddle-stitched, occasional, (mostly) black-and-white anthology. The result is Fiesta-Magasinet and in many ways it’s like the Eighties or Nineties all over: three highly accomplished cartoonists and a bunch of invited talent producing short strips purely for fun and pouring their heart into it. Smet continues to refine his particular type of cartoon (e)scatology and philosophy, pushing the limits of cartoon readability while aiming his always mordant satire at identity politics. Kielland finds a winning formula by having dictators such as Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-Un and Recep Tayyip Erdogan tell us about their comics collections. And Krarup continues his long-running, harrowingly funny adventures of the dysfunctional and homosocial everyday heroes Bruce and Robin. Fiesta has so far appeared with surprising regularity — five issues are out already, plus a special edition devoted to the end of the world. Excellent work by such underground luminaries and up-and-comers as Line Høj Høstrup, Christian Henry, Clara Jetsmark, Nanna Amstrup and others are the icing on the cake. Who would have thought an anachronistic endeavour such as this would become a platform for some of the best Danish comics of the moment?

Grus (‘Gravel’)

by Anna Degnbol

Fahrenheit

In her second graphic novel, Degnbol tells the story of a woman who returns to the small countryside town in which she grew up to tend to her mother after she has fallen into a coma. Degnbol marshals the well-established narrative device of physical homecoming, triggering a return to an unresolved past with great sensitivity and narrative purpose. The flashbacks she interweaves from the protagonist’s youth are pitch-perfect renditions of high school anxiety and abandon, while the tersely staged present-tense narrative combines empathetic psychological realism with a bona fide ghost story of the kind that might feel contrived, but reads as an entirely natural enhancement of the story. Degnbol’s visual storytelling is unfailingly clear, while suggestively textured in ways that are reminiscent of cartoonists as different as Debbie Drechsler, Jason Lutes, and Edward Gorey. This book establishes Degnbol as a major emerging voice in Danish comics.

Tusindfryd (‘Daisies’)

by Signe Parkins

Cobolt/Aben Maler

Parkins is amongst the most imaginative and provocative drawers in Danish cartooning. In this, her most satisfyingly resolved book to date, she combines more or less randomly generated verse with free-form drawing to craft a sustained lyrical mediation on sex, gender and nature. She avidly employs organic metonymies, such as plants and insects doubling as signifiers of human procreation and ageing, as well as motifs of dissection and small-box categorisation to describe the way we inevitably order our life. One senses suppressed rage in the otherwise light-footed, intoxicatingly flowering proceedings and it seems to be here that Parkins needs to concentrate her energies in the future, without flinching, if she wishes to take things to the next level. In the meantime, these are exhilaratingly distinct and enjoyable comics that deserve an international audience.

Hjem (‘Homes’)

by Bue Bredsdorff

Basilisk

A small slip-cased collection of four thematically-linked mini-comics produced by Bredsdorff over the last few years, this publication pulls into focus his distinct talents as a visual storyteller and chronicler of the intersection between place and memory. “Huset i Sønderhå” (‘The House in Sønderhå’) threads together individual verbal-visual details, that are simultaneously memories, of the artist’s childhood home in the Danish countryside; “Husumgade 30” (´Husum Street 30´) does the same for his bachelor’s pad in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen, while “Ly” (‘Shelter’) mixes things up by detailing visually the construction of a small wooden house in almost DIY-catalogue fashion, but rendered with a nervous line that enunciates emotional investment. The contrast to the smudged pencil of the preceding booklets, “Ly” brings Bredsdorrfs memories into the present and applies them to the fundamental theme of (literal) homemaking, of constructing where we belong, in every sense.

Fortress

by Sofie Louise Dam

The Animation Workshop

Last year saw the first class graduate from the newly-established four-year Visual Storytelling programme at the Animation Workshop in Viborg, a major new institutional presence in Danish comics and cartooning. Sofie Louise Dam is one of several distinct talents to have emerged from that first crop and her graduation comic is a remarkably confident work of comics reportage. Marking the centenary of Denmark’s sale of its three West Indian Colonies, St Thomas, St John and St Croix, Dam travelled there to meet an American descendent of Danish-owned slaves, a contemporary of hers, to learn together about their shared past. She works in a sketchy, digitally drawn line and two tones of colour reminiscent of Frank Santoro’s work to detail a fairly banal tourist visit and summarised narration of the discussions and thoughts it brought to the two travellers. While no profound insights are gained, it’s an earnest and quietly powerful chronicle of discovery that prompts questions of Danish self-understanding through the elucidation of a past, which we as a nation have collectively wiped from our imagined community.

Finland

Selected by Harri Römpötti

Harri Römpötti has worked 30 years as a freelance Helsinki-based journalist specialising in comics, cinema, music and literature. He’s written books on Finnish comics and documentary cinema and curated comics exhibtions in Helsinki and abroad together with Ville Hänninen. He also curated a programme of animated films related to comics for the Stuttgart Animation Festival in 2015. The program was also shown at the Tampere Film Festival in 2016.

Armo (‘Mercy’)

Armo (‘Mercy’)

by Emmi Valve

Asema Kustannus

In Armo Emmi Valve tells her readers about her long running mental health problems more openly than she would to her therapists. The nearest comparison in lack of inhibition is the old master of autobiographical comics, Robert Crumb. Valve has made autobiography before, but at 300 pages Armo is her major work and real breakthrough. Her structure of flashbacks could be confusing, if it wasn’t extremely carefully constructed and composed. In wild psychedelic colours, Valve draws the distressing mood of her struggle, which started when she was three years old. For her, art is not therapeutic like for Crumb, as he admitted himself. Valve says that she became an artist despite her illness, not because of it. By the end – like in the book’s name that means ‘Mercy’ or ‘Grace’ – there glimmers a spark of hope.

Vihan ja inhon internet (‘Internet of Hate and Disgust’)

by Johanna Vehkoo & Emmi Nieminen

Kosmos

Journalistic comics have rapidly been getting more common in recent years but good examples are rare except for Joe Sacco’s. Even Vihan ja inhon internet suffers from being text-heavy like so many. But only a little and it is a very ambitious work. Written by experienced journalist Johanna Vehkoo, it dives deep into the racism and misogyny which have become intertwined and mainstream on the Internet and in social media. A specialist in media, Vehkoo has interviewed victims, researchers and even a few hate-mongers. Journalistically the album is flawless. Emmi Nieminen draws in an effective and effortless style that is a pleasure to the eye. The problem of the abundance of text and undramatic talking heads has been noted and the exceptionally large format helps by allowing a lot of space for the images. Still the album feels often more like a heavily illustrated text than a comic; however, better journalistic comics are hard to find.

Eka kerta (‘The First Time’)

by

Petteri Tikkanen

Like

Petteri Tikkanen has been following his character Eero for over ten years in five books. Together they form a coming-of-age story or a Bildungsroman in comics form. Eero is on the threshold of adulthood, his military service behind him, and ready to move away from home. He’s still to lose his virginity. Prophetically the title of this book means the first time. Tikkanen has always drawn in round and deceptively simple brush-lines that place him in the proud school of the ‘Clear Line’. He opens the book with a six-page silent passage that anchors Eero to his wintery environment. It closes with an equally muted seven pages. Even inbetween there’s little speech. The images – expressions, glances, gestures – do the talking. The atmosphere is calm even though the story deals with deep emotions. There’s a hint of sadness. Tikkanen seems to be saying farewell to Eero, who is leaving home and entering adulthood, something which doesn’t belong anymore to the story in this series of books.

Flanders

Selected by Gert Meesters

Gert Meesters is associate professor of Dutch language and culture at the University of Lille, France. He is a co-founder of the comics research group Acme in Liège, Belgium and co-edited essay collections about French publishing house L’Association and about independent comics publishing (bilingual English-French). Since 2001, he has been writing weekly comics reviews for the Flemish news magazine Knack.

Wolven (‘Wolves’)

by Enzo Smits & Ward Zwart

Bries

Hazenberg is a village surrounded by woods, a fictitious place, somewhere halfway between Belgium and the United States. It is the setting of Wolven (‘Wolves’), the first book length comic by Ward Zwart and film director Enzo Smits. As if it were the opening credits of a television series, Zwart starts the book with a gallery of scenery and portraits to establish the right atmosphere. Houses look deserted and chaotic, young people do not seem to belong here. Several stories share this setting during a hot summer. Adolescent boys try to kill time and go looking for a wild animal, but find something completely different. A loner lets himself be persuaded to go to a party, but things get out of hand really quickly. A skater has a head wound that causes visions of himself with film legend James Dean.

Zwart and Smits evoke a time of endless boredom that presents adolescents with the opportunity to discover their personalities while venturing off limits. Zwart has been a small press favourite for years. His dreamy pencil drawings full of thoughtful details and tacit faces bring the reader in a nostalgic universe. He has a preference for unfinished drawings. Too tidy lettering or glossy paper would not fit with his stories. Wolven is also very special as an object. Several extras make it a treasure trove: a newspaper article glued into the book, a flyer of a closed theme park and a mini-comic with the bizarre story of a man who features in the other chapters of the book. Wolven is a whole world in which you can retreat. Not bad for a debut, I would say. Also available in French from Même pas mal.

Papa Zoglu

by Simon Spruyt

Bries

Fairy tales are fairly common in comics, but fairy tales for adults are not. Papa Zoglu, the newest book by Simon Spruyt, winner of the Willy Vandersteen prize for best Dutch language comic with his previous book Junker, fits into that category. His story about Zoglu, a child that is born from a cow and transforms into a bull with a moustache during his adolescence, plays with the genre laws of fairy tales, but distances itself from them as well. The witch who raises Zoglu leaves him without much further ado. Zoglu starts wandering, thus inviting the adventures that are part and parcel of the genre. By chance, Zoglu makes it possible for three unusual couples to have a child, which causes the progeny of these couples to worship the young boy with the moustache. Zoglu himself starts a family as a bull, but is less lucky.

In spite of the repetitions and other typical fairy tale elements, which Spruyt accentuates in his storytelling, many twists and turns in Papa Zoglu still come as a surprise. This is the result of Spruyt’s rebellious fantasy, his humour and his literary talent, but it’s the visuals that really single out this book. Spruyt has studied the look of medieval manuscripts and modelled the book after them. He does not follow the laws of perspective and the characters look like puppets, as they look completely alike in different images. But that is not the only remarkable aspect in the graphics. Spruyt also gives the two-dimensional line drawings texture by applying warm watercolours, making the pages look artistic and well-executed. Papa Zoglu is at a crossroads of medieval illustration, picture books, a puppet show and a traditional comic. Also available in French from Même pas mal.

Italy

Selected by Matteo Stefanelli

Matteo Stefanelli is a media scholar at Università Cattolica of Milan, and a comics critic and curator. He has written on comics for several newspapers and magazines, and published books on the theory and history of comics including La bande dessinée: une médiaculture (Armand Colin, 2012) and Fumetto! 150 anni di storie italiane (Rizzoli, 2012). He is the founder of comics culture online magazine Fumettologica.it.

Ghirlanda (‘Garlandia’)

by Lorenzo Mattotti & Jerry Kramsky

Logos

More than ten years in the making, Ghirlanda is a book of marvels, because of its story, set in a fantasy world inhabited by imaginary creatures, focused on the adventurous journey of a shaman in search of his beloved. But also because of the enchanting line in black and white of Mattotti. In their longest graphic novel the authors tell a metaphorical and dreamlike tale about human instincts, even the most abject ones, even in a dreamlike fairytale. And what we feel during the reading is a dance for/with our gaze, hypnotised by the mastery of the greatest linework we can possibly imagine in contemporary comics.

Mercurio Loi

by Alessandro Bilotta & various artists

Sergio Bonelli Editore

If you think that Italian serial “floppy” fumetti, still mainly sold on newsstands, are vintage stuff, and maybe boring, don’t try this. Ok, it’s verbose. And it’s boring: no action, no punches. But every episode is a surprise, a challenge to the reader’s expectations. Mercurio is not a “Bonelli hero”: he’s just a “flaneur”, a particularly brilliant man who likes to wander through the streets of his Rome in 1826, and get carried away by the emotions provided by meetings, coincidences and inconveniences at every corner. The series is not even historical fiction, but a vague walk in the past that focuses more on the intellectual games of the protagonist. In the end it’s a story that offers itself as a way of thinking about narrative devices (not only in Bonelli’s model, and not only in comics). Thanks to the writer Bilotta and also to the quality of artists - from Manuele Fior (covers) to Andrea Borgioli, Sergio Ponchione or Francesco Cattani - Mercurio Loi is already one of the best series Bonelli have ever made.

Luna del mattino (‘Moon of the Morning’)

by Francesco Cattani

Coconino Press

Seven years after his first book, Barcazza (Canicola Edizioni), which won him the Best Emerging Talent Award at Napoli Comicon in 2010, Cattani comes out with a choral story that photographs the deviant reality of this Italian province, made up of small things, meetings, clashes and missed opportunities. The story develops within twenty-four hours, during one day of what is called the hottest winter of all time. In a spiral of events that degenerate into a series of violent and wicked acts, we follow the daily story of the characters who revolve around the little boy, Tommi. From his dissolute brother to his warehouse friend who passively undergoes his own alienating work, the story proposes itself both as a tale of the growing pains of the young protagonist and as a metaphor for the unpredictability of life. A tale that is very strong, and very well crafted.

Il grande prato (‘The Great Meadow’)

by Roberto Grossi

Coconino Press

This is the debut in graphic novel form by Grossi, an architect who builds a compelling narrative both about the environment (a very poor and deteriorated suburb) and about characters (two orphan twins). In the middle of an urban nowhere, these kids struggle to understand the reasons behind the violence and marginalisation, while people burn down refugees’ or Romani people’s camps. They live in a shack with a sick uncle, just trying to survive in and around a meadow that looks like their existential prison, but is also their only vital space. Grossi’s line is as thick and robust as it is delicate, especially when focusing on the faces - and big eyes - of the characters. Tales of the marginalised are nothing new, but the author’s sensitivity is so deep and limpid that he really manages to make us feel scared.

Il signor Ahi e altri guai (‘Mr Ahi and Other Troubles)

by Franco Matticchio

Rizzoli Lizard

The reclusive Matticchio, one of the best illustrators from Italy (you may have seen some drawings by him in The New Yorker) is finally back in print with a new anthology of his quite sporadic comics. The book collect the stories of a character whose extravagance is typical of Matticchio: a blind man, whose head is shaped like an eyeball. Matticchio, in his comics as in his illustrations, plays with images evoking contradictions which test the reader and their certainties, mocking reality itself. Mr. Ahi amplifies with his giant eye the disenchanted gaze upon the typical world of Matticchio’s work: everything is upset and everything is surreal, thanks to the unpredictable inventiveness of an author who recalls here the art of Edward Gorey and also echoes Peter Arno, but filtered through Franz Kafka.

Bonus list: Lunanera by Barbara Baldi (Oblomov); Brucia by Silvia Rocchi (Rizzoli Lizard); and Zambesi by Paolo Cattaneo & Fabio Tonetto (Self-published).

Poland

Selected by Michał Chudoliński

Michał Chudoliński is a comics and film critic. Chudoliński also provides lectures on American mass culture, specialising in comic book culture (Batman Mythology and Criminology) at Collegium Civitas. Founder and editor of the Gotham in Rain blog. Co-operating with magazines like Polityka, 2+3D, Nowa Fantastyka, Czas Fantastyki, Charaktery and on Polish Radio. Currently working for Polish Television TVP and TVP Magazine.

Totalnie nie nostalgia: Memuar (‘Absolutely not nostalgia: Memoir’)

by Wanda Hagedorn & Jacek Frąś

Kultura Gniewu

Without any doubt the best Polish graphic novel of 2017. Outstanding and autobiographical, Wanda Hagedorn’s story is about growing up in communist Poland and its characteristic vision of women, smothered and discriminated. Hagedorn emigrated to Australia in 1986, where she’s worked in NGOs, coordinating gender studies and violence against women projects. The 240-page memoir tells a story of her growing up, her family’s social life and psychic portraits, putting an emphasis on her sisters, mother and grandmother. Writing about their fight for freedom, she disputes on the old, typical model of a socialist Polish family. The storyline wouldn’t be as marvellous if it wasn’t for the metaphorical and brilliant graphic work by Jacek Frąsia. The artist did a great job portraying the world from the perspective of a child, marking characteristic, childish exaggerations, which bring to mind the style of magical realism. This graphic novel is a great opportunity for a reader to see and understand Polish reality from before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Bajka na końcu świata (‘Fairytale at the end of the world’)

by Marcin Podolec

Kultura Gniewu

An unconventional mix of a children’s story and a post-apocalyptic comic. Wiktoria and a dog called Bajka (or ‘Fairytale’) wander through a dead and destroyed universe to find her parents. The environment is not human-friendly; it’s full of abandoned houses, poisoned rivers and toxic rainfalls. Despite a pessimistic vision, Marcin Podolec manages to sneak in a share of an unforced humour. He proves that even in the worst situation one can find friendship, joy or simply cope with the adversities. Podolec definitely is a hope for Polish comics, at the same time being one of the most productive authors both in animation and comics.

Anastazja tom 1 (‘Anastasia’ Vol. 1)

by Magdalena Lankosz & Joanna Karpowicz

Kultura Gniewu

Joanna Karpowicz and Magdalena Langosz show readers the Hollywood of the 1920s in a stylish, moody crime story. In search of their American Dream, a mother and a daughter come to LA thinking of becoming actresses. It soon becomes obvious that working in the ‘Dream Factory’ is not what it seems from first glance. The authors’ duet shows that Harvey Weinstein’s way of living wasn’t any different back in this period. The vision in this story shows the portrait of a woman in the film industry told between the lines of the Hollywood history – i.e. the grim legends of The City of Angels such as the suicide of Peg Entwistle, Fatty Arbuckle’s case or the murder of the Black Dahlia. An honest panorama of the colours of Hollywood and a consequent demonstration of standards of behaviour which have survived in show business up to this day.

Bradl

by Tobiasz Piątkowski & Marek Oleksicki

Egmont

A great example of how to show the Polish reality during World War Two in the style of American comic books. The protagonist is presented as Kazimierz Leski (AKA Bradl), a participant in the Warsaw Uprising and a spy who acquired some of the most important secrets of the Third Reich. The authors, Tobiasz Piątkowski and Marek Oleksicki, create a spy thriller with a rapid storyline and intrigue, while at the same time appraising pulp and noir aesthetics. An extraordinary example of the popularisation of a rich and outstanding history of wartime Poland, retold in a modern way.

Tylko spokojnie (‘Take it easy’)

by Henryk Glaza

Kultura Gniewu

The full-length, 164-page graphic novel debut of Henryk Glaza centeres around dying in today’s Poland. It’s an authentic story of a pedagogue from Gdańsk who finds out about his diagnosis of cancer. An emotional drama portraying a vision of approaching death and a situation which changes lives, not only of the patient, but also his relatives and friends. The story is accompanied by the works of musical giants including Miles Davies, Neil Young and Bob Dylan.

Bonus list: Na szybko spisane 1980-2010 by Michal Sledzinski (Kultura Gniewu); Powstanie – film narodowy by Jacek Swidzinski (Kultura Gniewu); Bellmer: Niebiografia by Marek Turek (Kultura Gniewu); Lux in tenebris vol. 3: Jellinge by Slawomir Zajaczkowski & Hubert Czajkowski (Unzipped Fly Publishing); and Relax. Antologia opowieści rysunkowych #2 by various artists (Egmont).

Portugal

Selected by Pedro Moura

Pedro Moura is a freshly minted PhD (University of Lisbon and Catholic University of Leuven) who currently researches and writes on comics and trauma. Based in Lisbon, Portugal, he has been writing reviews, and peer-reviewed articles on comics for the past 15 years. He writes on comics for his Portuguese-language blog Lerbd, as well as collaborating in both print and online media such as The Comics Alternative and 9.org. He has also created a documentary on Portuguese comics.

Disclaimer: as my comics scriptwriter activities are taking precedence over my critical ones in Portugal, I have increasingly participated in a number of projects or collaborated with artists, some of which I’ll quote on this list below. So next year, Gabriel Martins will take over my role for this list. I’d like to thank Paul for his kindness and welcoming arms throughout these years.

Considering the last few years, which have brought a successful streak of new books from both veteran artists and many newcomers, in what one could call the strengthening of the contemporary Portuguese market, no matter how small in comparison to other European countries, 2017 was slightly less fortunate. But that’s from a merely quantitative point of view, as in terms of quality, it is always possible to find books that, given the chance, might well be placed side-by-side with some international titles. As usual, my list is more an attempt to show the diversity of contemporary Portuguese production than a simple “best of” from whatever narrow perspective.

There were some adaptations of both literary and non-fiction projects and even of real events into comics, such as Xavier Almeida’s autobiography-styled Santa Camarão about an Algarve boxer from the 1930s, and Filipe Melo and Juan Cavia’s Comer/Beber, which tells a story about the last wish of a death-row inmate. The informal collective The Lisbon Studio debuted their own anthology series, with short stories (I am one of the writers), which has proven to be a successful formula. There are also new publishers, from small press and fanzine circles, that have put out very diverse work of people who may grow into household names, if given the right opportunities. But let’s focus here on stand-alone books.

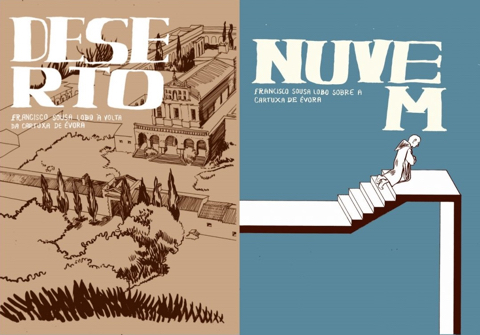

Deserto/Nuvem (‘Desert/Cloud’)

by Francisco Sousa Lobo

Chili Com Carne

There is no doubt that Lobo’s obsessive and proficient output is even more surprising for both its aesthetic and philosophical commitment. I’ve argued elsewhere that Lobo’s overall project touches an incredibly original and complicated autobiographical or auto-fictional project, but this double book (two titles, Desert and Cloud, bound back-to-back) ticks all the boxes of a straightforward autobiography. Lobo spent some time visiting Évora’s Carthusian Monastery of Santa Maria Scala Coeli, with the goal of creating a sort of ‘live’ comic project. Based on his observations, talks and theological discussions with the monks, Deserto explores issues such as isolation, silence and the relationship with God, which genuinely concern Lobo as an anxious, suffering Catholic artist (a pleonasm, I’m certain). Nuvem, on the other hand, takes the shape of short letters, addressing the history of the order and this monastery, as well as some of the concerns mentioned above. One half complements the other, reinforcing the themes and clearly making them an intrinsic ingredient to the artist’s recurrent obsessions.

Lugar Maldito (‘Damned Place’)

by André Oliveira & João Sequeira

Polvo

Mixing elements from genres and tropes such as the road trip, family drama, noir, horror and dark fantasy, Lugar Maldito is the story of a Samuel and Maria, who flee their families and the city after having a baby. They are in the pursuit of happiness and isolate themselves in a house in North East Portugal. But one could describe the story as a sort of Flight into Egypt meets The Shining. Samuel’s secrets, an external, supernatural threat and the impeding doom of justice all close in on the couple to amp up the suspense. Told in Sequeira’s frantic, nervous slashed lines and incredibly expressive brush-stokes, the action scenes are interrupted by the pages of Samuel’s diary, giving us yet another level of psychological insight into the character but also the perilous build-up towards the tragic end.

Nagual

by Diniz Conefrey

Quarto de Jade

This comics veteran has been seriously exploring, as an amateur scholar and creator, Pre-Colombian Mexican culture (the complicated network of the cultures named Nahua, Aztec and/or Mexica) for years, having written extensively about them, prepared workshops and created a cycle of almost classical European-styled albums with The Book of Days. The volume under discussion collects a number of short black-and-white stories that have been either unpublished or published in magazines with small print runs. All the stories tackle issues associated with that central interest. Most of the short pieces can be described as poetic, as they are less interested in following a linear story focused on a character than creating an ambient structure around a theme or a Mexica text, about a god figure, the origin of a natural phenomenon or resource. Being the most engaged of abstract comics practitioners of the country, some of the pages by Conefrey live on a very fine line between full abstraction and floral and animal motifs, creating an undefined territory that taps into philosophical concerns present in both the addressed culture and contemporary thought (Deleuze’s and Guattari’s becoming-animal is the operative term here).

Bruma (‘Mist’)

by Amanda Baeza

Chili Com Carne

This is an anthology of Baeza’s unrelenting output of short stories, published a little everywhere, from Portuguese magazines to stalwart trans-European titles such as Kovra and Volcan, including her own mini-Kuš title, Our Library (not included in the English edition). The Chilean-Portuguese artist is a serious reinventor of comics’ specific visual storytelling possibilities, experimenting with page composition, multiple storylines, diverting attention, not to mention the sheer diversity of materials she uses, always looking for the best option in any given project. But thematically speaking, she is also creating a path of her own, mixing autobiographical traits such as identity-building and crisis with political stances, the deconstruction of prejudices and the questioning of nationality. (A disclaimer: I wrote one of the short stories).

Conversas com os putos (‘Talks with the Kids’)

by Álvaro

Polvo

Álvaro is a satirist who has been putting out a number of books with his short strip-like stories, more often than not concentrated on a single situation – a xerox copy shop, the living room of an obnoxious couple, the Nativity scene – and then releasing the most universal and distinctive trait of humans: inherent stupidity. Talks with the kids is also his most autobiographical book, as the main character is, just like the author, a private tutor (of descriptive geometry, to be exact). The talks range from homework and understanding basic maths to movies, culture and life. The worst aspect about the hilarious things the kids say in this book is that they’re not made up.

No caderno da Tangerina (‘Tangerina’s Note Book’)

by Rita Alfaiate

Escorpião Azul

A light-hearted tale about a monster-slaying girl who has just arrived at a small village. Told in small chapters from the point of view of a boy, this book is clearly the product of a steady diet of Ghibli-influenced world-building and monster stories. Without excessive fanfare, the author shows incredible yet eerily slow-paced storytelling chops, all the better to wow us when the going gets tough. With an almost minimal but expressive line work, Tangerina’s note book is a short little classic, putting Rita Alfaiate immediately into the “artists to follow” category.

Spain

Selected by Alfons Moliné

Alfons Moliné is an animator, translator and writer on comics, animation and manga. He is the author of a number of books, including El Gran Libro de los Manga (Glénat, 2002) and biographies of Osamu Tezuka, Carl Barks and Rumiko Takahashi.

Pinturas de Guerra (‘War Paints’)

by Ángel de la Calle

Reino de Cordelia

Ángel de la Calle is a writer, illustrator and comic critic active since the late 1970s, known especially for Modotti, una mujer del siglo veinte (‘Modotti, a Woman From the 20th Century’), based on the life of Italian photographer Tina Modotti (2 vols. in 2003 and 2005; revised edition in one single volume in 2007). He now presents his newest graphic novel in over a decade, and it was certainly well worth waiting for: Pinturas de guerra is an excitingly complex 300-page work in which a Spanish writer (allegedly, the author himself) moves to Paris in the early 1980s in order to produce a biography of actress Jean Seberg. He settles in an apartment in which live several Latin American refugees with whom he will be able to mingle and share experiences… and get tangled in a political turmoil. This enables De la Calle to depict the tragic repressions that shook such countries as Argentina and Chile during their respective dictatorships, but also the role played by such organisations as the CIA or the French secret services to sustain those repressions. The plot also includes nods to the artistic movements of the period, or to well-known Latin American writers like Gabriel García Márquez or Julio Cortázar. The black-and-white artwork, sketchy at times, but always rich in details, matches the story effecitvely, with a clever use of lights and shadows that borders on Expressionism. Like Joe Sacco, De la Calle proves to be a master of graphic investigative journalism: even if Pinturas de guerra takes place in an ‘alternate reality’, he succeeds in creating an accurate reflection of the cultural and political scene of the times in which the story is set, while condemning the abuse of power. Pinturas de guerra has deservedly won the prize for Best Spanish Comic of 2017, awarded in the Saló del Comic of Barcelona.

Carvalho: Tatuaje (‘Carvalho: Tattoo’)

by Hernán Migoya & Bartolomé Seguí

Norma Editorial

The character of Pepe Carvalho, a cynical, bon vivant private eye, was created in 1972 in literary form by Manuel Vazquez Montalbán (1939-2003), one of Spain’s most renowned roman noir writers, for a successful series of crime novels. After having been adapted into movies and television, Carvalho now makes his debut in comics with this graphic novel, written by Hernán Migoya (some of whose previous works I have reviewed on this site here and here). It is drawn by Bartolomé Seguí, a Majorcan talent with a 35-year old career, whose previous work includes the award-winning Blind Snakes (2008, script by Felipe Hernández-Cava), a thriller set in the Spanish Civil War. Migoya adapts one of the first Carvalho books, Tatuaje, originally published in 1974, and the result is more than satisfactory. A dead body appears inexplicably on a beach near Barcelona, with a tattoo on his skin that says “I was born to revolutionise Hell”. It is up to detective Carvalho to find out the identity of the mysterious corpse, embarking on a case that will lead him to the canals of Amsterdam… Seguí’s artwork faithfully portrays 1970s Barcelona, with a masterful, nearly psychological use of colour and lighting. Tatuaje has been both a critical and sales hit, and Migoya and Seguí are currently working on further adaptations into comics of the Carvalho saga.

Arde Cuba (‘Cuba is Burning’)

by Agustín Ferrer

Grafito Editorial

Although he started drawing comics in the early 1990s, it was not until 2011 that Agustín Ferrer became a full-time comics author, achieving a big success in 2015 with his graphic novel Cazador de Sonrisas (‘The Smile Hunter’). Set in the 1950’s, ie in pre-Castro Cuba, the main character of Arde Cuba is Frank Spellman, a photographer who travels to the Caribbean island in the company of movie star Errol Flynn to assist in the shooting of a film. But Spellman does not know that this job will involve him in a plot to preserve the dictatorial government of Fulgencio Batista against the advance of Fidel Castro’s troops. The meticulously documented story involves both fictitious and real characters, such as Camilo Cienfuegos, a key player in the Cuban Revolution, who mysteriously disappeared in a plane crash in 1959, shortly after Castro’s triumph. Most of these characters are skilfully depicted by Ferrer, as are the backgrounds, including the urban Havana of the period and the tropical jungle. It’s an exciting blend of reality and unreality, that does not pretend to offer a faithful portrait of the Revolution, but instead succeeds in creating a thrilling plot… and in making us wait heartily for Ferrer’s next work, a biography of Dutch architect Mies van der Rohe, scheduled for mid-2019.

Don Talarico: El Castillo Encantado (‘Don Talarico: The Haunted Castle’)

by Jan

Amaniaco

Juan López, alias Jan, is one of Spain’s most famous children’s comic authors, with a career that spans over six decades, especially known for his humorous superhero Super López, who has starred in over 70 albums to date and has recently been adapted as a live-action movie. In 1971, Jan created a short-lived but brilliant character, Don Talarico, a medieval knight, for the comic weekly Strong. After that title was cancelled, its publishers, Ediciones Argos, contacted Jan to draw a new Don Talarico 48-page story to be published directly in album form. Unfortunately, shortly thereafter, the publishing company closed its doors, the album was never published, and Jan was never able to recover his original artwork. 45 years later, this ‘lost’ comic has finally seen the light of the day. Luckily, Jan had saved some primitive photocopies from most of the original pages, as well as a draft of the script. Using those materials, he has been able to re-draw the whole story. The result is a hilarious romp set in the times of the Reconquista, when the Muslims dominated most of the Iberian peninsula and Don Talarico and his men must conquer a castle dominated by the Moors with the help of a goofy wizard. There are neither heroes nor villains: both the Moors and the Christian knights are equally ridiculed in this fast-paced, clever anti-war satire for all ages. Bonus features include some sketches and an insightful article on the restoration of this story. And if thou art able to readeth Spanish, mayhaps thou shalt enjoyeth ye dialogues, drafted in a flavourful bogus archaic Castillian!

The Netherlands

Selected by Gert Meesters

Gert Meesters is associate professor of Dutch language and culture at the University of Lille, France. He is a co-founder of the comics research group Acme in Liège, Belgium and co-edited essay collections about French publishing house L’Association and about independent comics publishing (bilingual English-French). Since 2001, he has been writing weekly comics reviews for the Flemish news magazine Knack.

Wills kracht (‘Will’s Power’)

by Willem Ritstier

SubQ

Last year, Willem Ritstier got the Stripschapsprijs, an old Dutch prize with a serious pedigree, for his entire body of work. He is a writer of many series that do not travel well, like Nicky Saxx and Soeperman, who are known by comics readers in the Netherlands, but not elsewhere. He drew Wills kracht (‘Will’s Power’), his first graphic novel, himself, because it’s a very personal book. His wife Will died eight years ago of cancer and this book tells the whole process from the diagnosis until her passing. Ritstier includes everything, from the scientific and alternative search for healing to everyday details and small-time conversations. He shows the effect the disease had on the whole family, with a daughter and a son. The book is very honest; in Ritstier’s own words, it is a monument for his late wife. He drew it in a style not unlike Dick Bruna’s Miffy. The minimalistic characters do not have a face. Only after reading, it becomes clear that the cover image is in fact his wife’s face. His recounting of the events is rather restrained and the events follow each other quickly, which makes it hard for the reader to feel the underlying emotions. However, the combination of the subject and the style make it a remarkable book.

Familieziek (‘Family Illness’)

by Adriaan van Dis & Peter van Dongen

Scratch Books

Writer Adriaan van Dis and artist Peter van Dongen both have a family history in Indonesia, formerly known as the Dutch East Indies. Their families moved to the Netherlands after the Second World War and Indonesian independence. Familieziek (‘Family Illness’) was written by Van Dis in 2002. It is a ‘novel in scenes’ based on his youth as the youngest child in a family from the colony. With Peter van Dongen he found the ideal graphic sparring partner. Van Dongen had already drawn a diptych about the period after the war in Indonesia, Rampokan and Celebes. Familieziek does not have a beginning nor an end. It is a situation sketch. The dark-skinned father of the house thinks he was treated unfairly. He is gentle with the horses he takes care of, but is tough with his son. The white mother is often desperate and seeks refuge in Indonesian superstition. Three daughters from an earlier marriage form a front with their mother against their stepfather. The boy dreams of imaginary friends and of the Indonesia he never knew, in order to compensate for his emotional neglect. In the meantime, the family experiences many problems that are common for refugees in our time: racism, unemployment and lack of interest.

One has to read Van Dongen’s comics carefully, because he tells a lot in the images. The voice-over in the captions is mostly from Van Dis’s novel, but by adding new visual scenes, the text gains depth. The historical backgrounds and everyday objects from the Fifties, in a quiet colour palette of browns and greens, feel like a part of the story. Van Dongen gets more and more recognition as a practitioner of Hergé’s clear line, which should be apparent looking at what 2018 has in store for him: a new Blake and Mortimer book written by Yves Sente that he drew with his colleague Teun Berserik, and a reprint of his classic Rampokan in French from Dupuis.