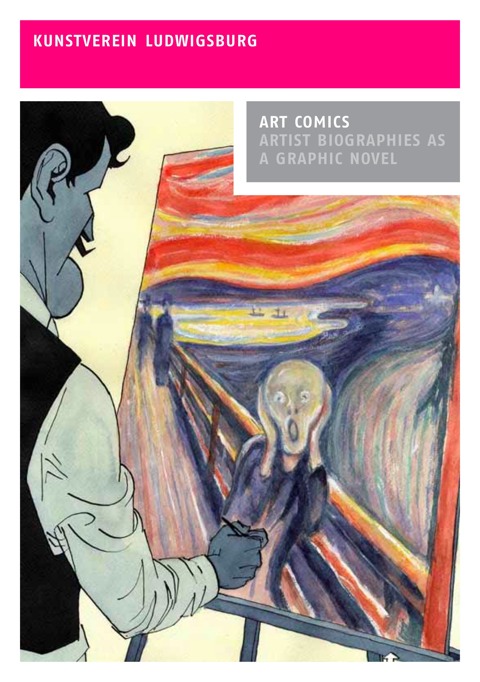

Art-Comics:

Artists' Lives As Graphic Novels

On Sunday November 23rd, the exhibition Art-Comics: Artists’ Lives As Graphic Novels opened at the Kunstverein Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart in Germany, presenting original comics art and preparatory materials from recent graphic biographies by six comics creators - two from Norway, two from the Netherlands, and two from France - about Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Munch, Schwitters, Gauguin and Schiele. This is my speech which I read in German to introduce the press and public to this significant exhibition.

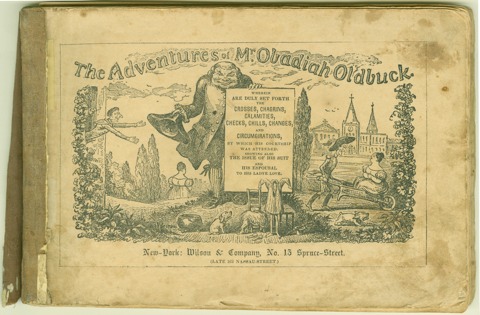

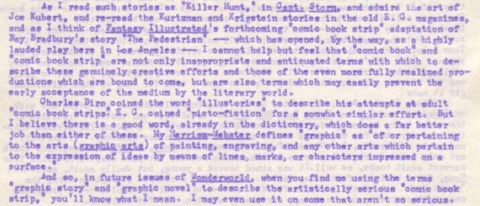

The concept of a complete work of comics in substantial book form can be traced back, in all but name, at least as far back as to the revolutionary albums of the early 19th century Swiss pioneer Rodolphe Töpffer (above), and indeed earlier still. The name ‘graphic novel’, however, was not coined in English until fifty years ago this month, in the second issue of the amateur press alliance publication Kapa-Alpha in November 1964 (below). At the end of his ‘Wonderworld’ essay, the American critic and dealer Richard Kyle proposed the ‘graphic story’ and by extension the ‘graphic novel’, as a provocative call-to-arms to creators to transcend the periodical, ephemeral, genre-defined nature of comic strips and comic books and to aspire to produce something more ambitious and lasting. Slowly at first during the Seventies, and then increasingly expanding, Kyle’s vision would become a reality, transforming the medium, its market and its status, not only in America but elsewhere, including Germany.

Richard Kyle introduces the terms ‘graphic story’ & ‘graphic novel’

Click image to enlarge

By 2005, the modern graphic novel had been catching on in Germany for many years. The issue remained, though, that some German journalists and publishing professionals had preferred to avoid the English phrase graphic novel altogether and tried to popularise various German terms like “grafische Novelle”, “Grafik-Novelle”, “graphischer Roman”, “Bildroman“, or the more general “graphische Literatur”, but no single term caught on in the book trade or the media. So in 2005, when my second book, Graphic Novels: Stories To Change Your Life, came out, Carlsen and other publishers in Germany were interested in translating it but were uncertain, especially about how to translate the title. Gradually, a consensus did emerge, especially once five publishers of German-language comics - major market leader Carlsen, Edition Moderne (1981-), Reprodukt (1991-), Edition 52 (1997) and Avant-Verlag (2001-) - joined forces to launch the website and blog graphic-novel.info in January 2008 (below). This portal has gone on to promote not just their own titles but also those of a growing number of other Germanophone publishers entering the field. Like that other now-familiar neologism imported from Japan - manga - the term graphic novel has crossed language and cultural barriers to become a truly international re-branding of comics.

Of course, the graphic novel is still fundamentally comics but in a new guise or disguise. This ‘makeover’ has helped institutions in the worlds of literature and the arts to reappraise the potential of the medium. This includes the Kunstverein Ludwigsburg which today is presenting the original artworks from contemporary comics on its gallery walls for the first time. The exhibition Art-Comics: Artists’ Lives As Graphic Novels, curated by Dr. Andrea Wolter-Abele, makes a perfect entry point for those less familiar with the graphic novel phenomenon, by demonstrating some of the varied, imaginative ways in which the growing genre of ‘graphic biography’ can re-tell the life stories of great artists in refreshing, accessible and illuminating ways.

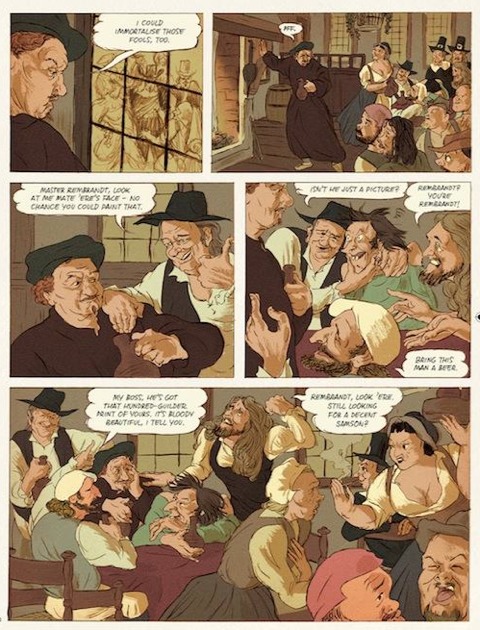

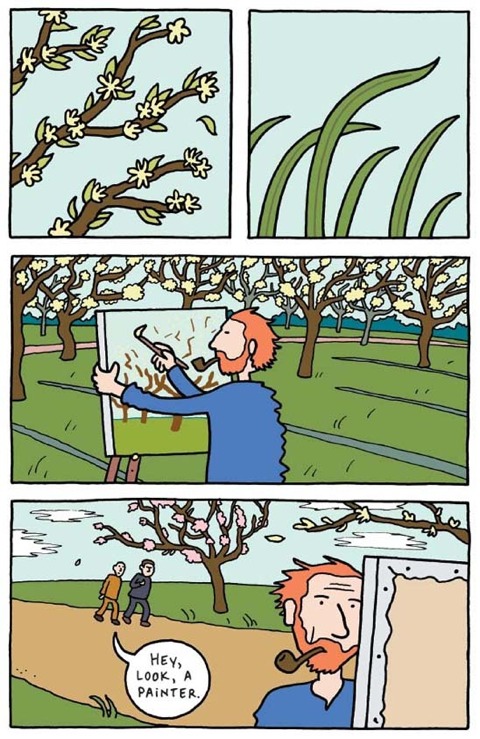

The challenge for any biographer is to identify and interpret those pivotal experiences and feelings that can fundamentally shape their subject’s life. While some graphic biographers will take on the full sweep of an artist’s lifetime, others choose to focus on their later years and dying days. Two of the graphic biographies included in this exhibition began as commissions from prestigious art museums, both as it happens in Amsterdam. The Riksmuseum had been closed for a 10-year renovation. In anticipation of its re-opening in 2013, they entrusted Dutch cartoonist Typex (a make of white-out correction fluid, so an appropriate pen-name for Raymond Koot) with the task of relating Rembrandt’s turbulent, compulsive life, looking at his daily life, his family, friends and rivals and how he interacted with them. Meanwhile the Van Gogh Museum sought out Barbara Stok who concentrated on Vincent Van Gogh’s last two years of intense creativity in the Provencal countryside and his close, supportive relationship with his brother Theo. (Both of these books have been translated into English by SelfMadeHero).

For both Dutch cartoonists these commissions were radical departures from their usual personal, self-generated output and became demanding and fulfilling projects. Typex and Stok immersed themselves in their assigned artist’s oeuvre, not to copy slavishly but to transform their drawing and distil a distinct, nuanced, entirely fitting style of their own, one that they had not employed before. Coupled with this is a fidelity to the artist’s voice, which also underlies many graphic biographers’ approach to their writing. Barbara Stok and Steffen Kverneland, for example, insisted that nothing should come out of their subject’s mouth that they had not spoken or written, requiring much intensive research and reading of correspondence and other sources. Through this processing of editing and integrating imagery and texts, the graphic biographer can combine the artist’s original artworks and original words through the visual-verbal interplay of comics into an insightful, often revelatory portrait.

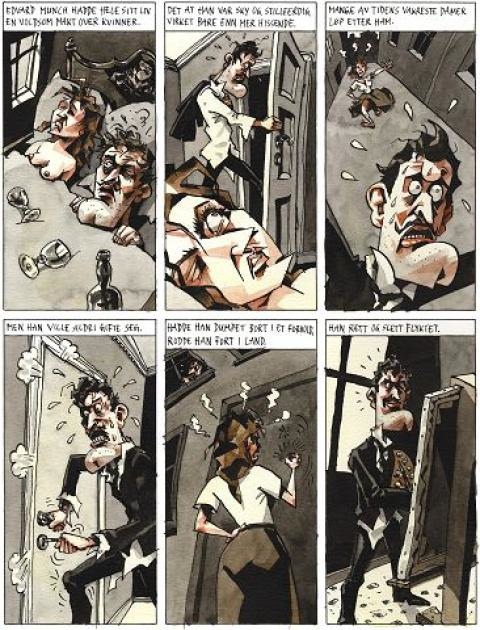

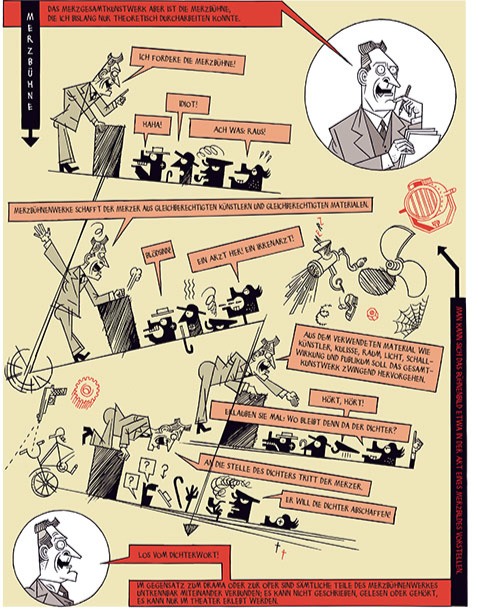

Since 2006, the Norwegian duo Steffen Kverneland and Lars Fiske have been serialising their individual biographies, of Edvard Munch and Kurt Schwitters respectively, in their more-or-less annual albums Kanon. Kverneland includes himself and his cohort as a satirical chorus undercutting the stuffiness of the museum world. Munch (No Comprendo) took seven years to complete, much of it spent digging through the artist’s private correspondences to uncover a different side to him from the widely known simplicity of his sadness and self-destructive excesses. A more complex and complete portrayal emerges, enhanced by Kverneland’s illustrations in a variety of styles, echoing Munch’s own changing approaches. Lars Fiske is if anything even more playful and irreverent in Herr Merz (No Comprendo), taking a Dadaist and collagist approach to reconfigure the language and layouts of comics to mirror Kurt Schwitters’ subversive originality. Fiske charts Schwitters’ lifelong determination and fierce optimism, despite great setbacks, and incorporates himself and Kverneland into the graphic novel, recording their travels through Germany, Norway and Britain to visit what little survives of Schwitters’ Merzbauen projects.

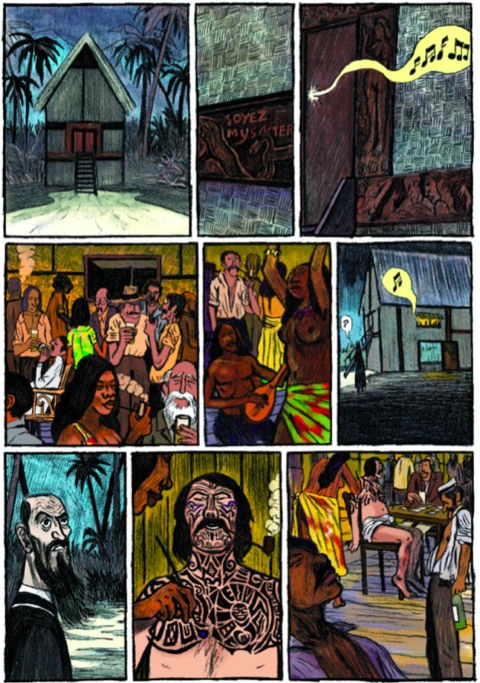

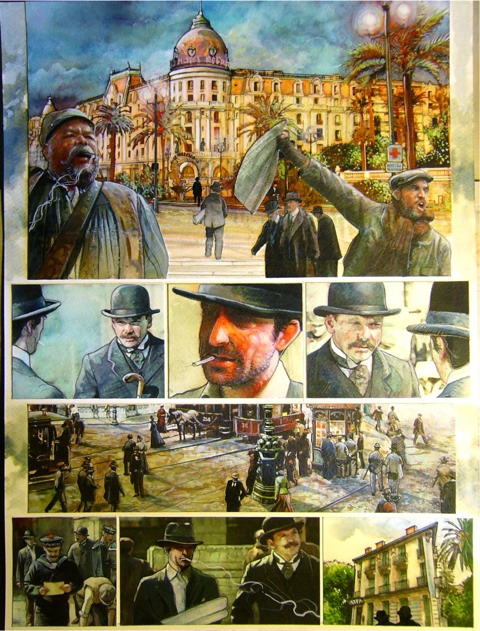

Rather than tackling a whole life, Maximilien Le Roy in Gauguin: Loin de la route (Le Lombard), drawn with expressive vigour and texture by Christophe Gaultier and coloured by his wife Marie-Odile, concentrates on the very last years of the painter’s life in self-exile in the Marquesas Islands, where his path crosses with that of writer and critic Victor Segalen. This retelling of history again tries to go beyond the familiar representations to bring out Gauguin’s values, vices and contradictions.

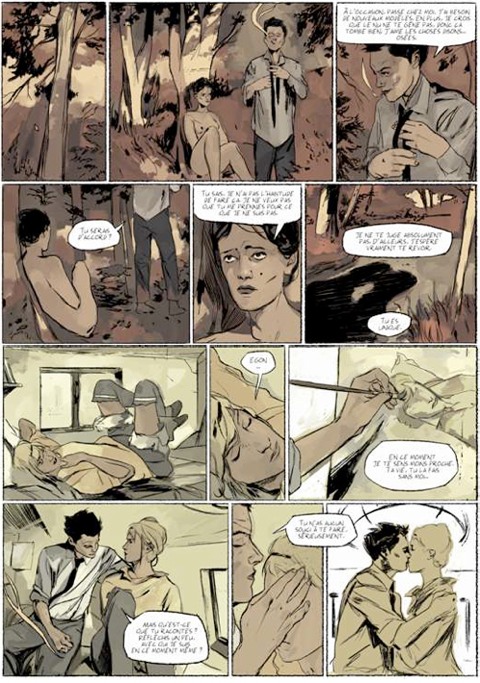

Xavier Coste’s debut Egon Schiele: Vivre et Mourir (Casterman) charts the life of the Austrian artist, cut short at the age of 28 by the Spanish flu epidemic, with an emphasis on his last years of celebrity and comfort as well as scandal and scorn. Rather than imitating Schiele’s art, Coste uses his own approach, but adapted to a palette of muted, melancholic colours reminiscent of the paintings by Schiele’s peers. With little biographical information available on Schiele, Coste elaborated what is known to flesh out the controversial prodigy’s story.

Graphic biographies present great opportunities and questions. How referential and how reverential should a comics creator be? How much or how little should the artwork in a graphic biography resemble the art of its subject? Should a biographer include herself or himself in a graphic biography? Should graphic biographies be made by creators from the same country and culture as the subject, or is that irrelevant? One thing is clear. Graphic biography of great artists is not some passing fad or opportunist vogue. The field is flourishing, especially in France. Notable recent additions include Laurent Seksik and Fabrice Le Hénannf’s Modigliani (Casterman), Dominique Osuch and Sandrine Martin’s Niki de Saint Phalle: Le Jardin des Secrets (Casterman) (both illustrated below).

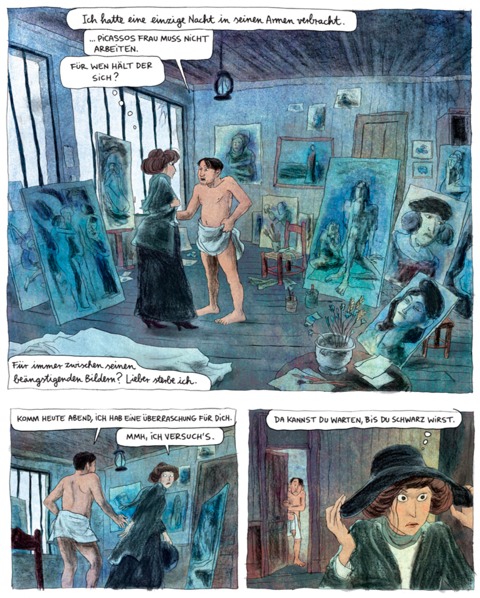

Julie Birmant and Clément Oubrerie’s Pablo (Dargaud) will be released in English in April 2015 from SelfMadeHero. Birmant and Oubrerie cover ten crucial years of Picasso’s career in four volumes totalling over 300 pages, several of which were exhibited this year at the Musée de Montmartre in Paris. Other fine examples have come from Canada, where Nicolas Debon examines four key periods in the life of Emily Carr, and from Japan where in 1987 the great manga author Shotaro Ishinomori investigated Hokusai’s obsession for perfection.

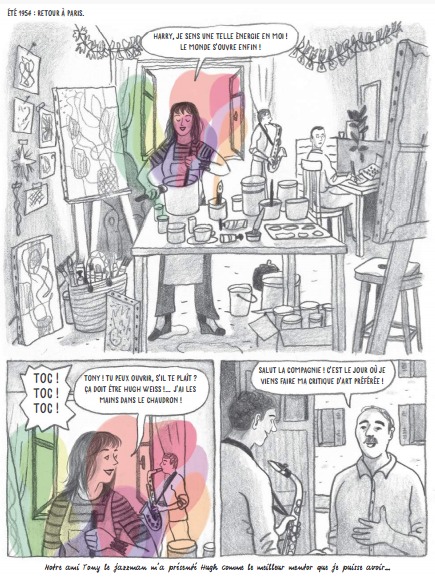

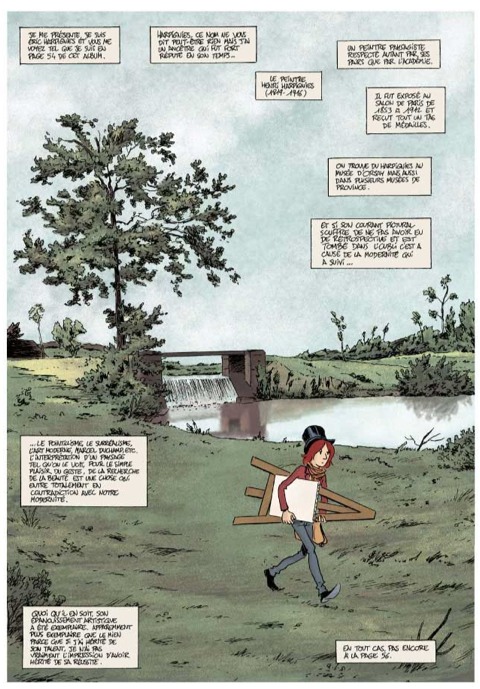

In this field, it is not solely the famous who are celebrated, but almost forgotten artists. In Harpignies (Pacquet), for example, we learn about the Barbizon landscape painter Henri Harpignies, as told by Darnaudet and Elric through a fictional present-day relative, also an artist, who looks back to his ancestor for inspiration.

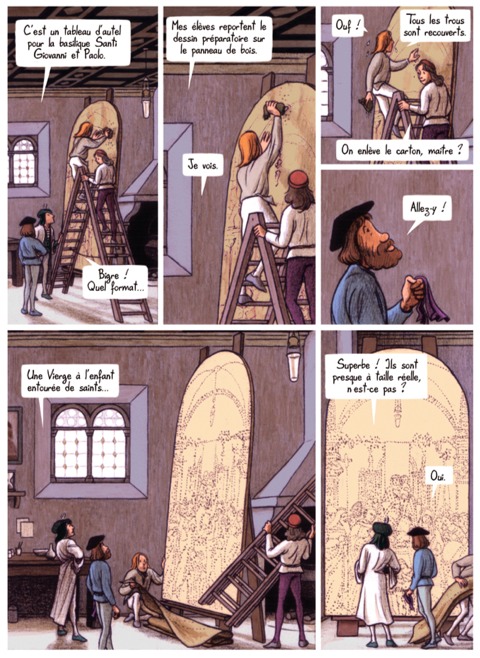

Other graphic biographies will narrow down to the genesis and secrets of one iconic painting. The background to Giorgione’s creation of his Renaissance masterpiece Sleeping Venus is the subject of the album La Vision de Bacchus (Delcourt) by Jean Dytar, while the meanings and mysteries of Las Meninas (Astiberri), the famous canvas by Velázquez, are revealed by the Spanish team of Santiago García and Javier Olivares.

As these examples show, at its best, graphic biography of artists and their art is developing into a rich, innovative genre of its own, alongside those of autobiography, reportage or graphic medicine. It can give us other fascinating perspectives on the struggles of an artist’s life, struggles that may resonate with our own lives. Graphic biography can also take us back to an artist’s work to see it with fresh eyes and deeper empathy. It also offers a wonderful introduction for newcomers to start exploring another art, the 9th Art as the French call it, the art of comics. I hope this landmark exhibition at the Kunstverein Ludwigsburg encourages visitors to discover more of the wonders of the graphic novel medium and to come to enjoy and appreciate its own remarkable writers and artists.

Postscript:

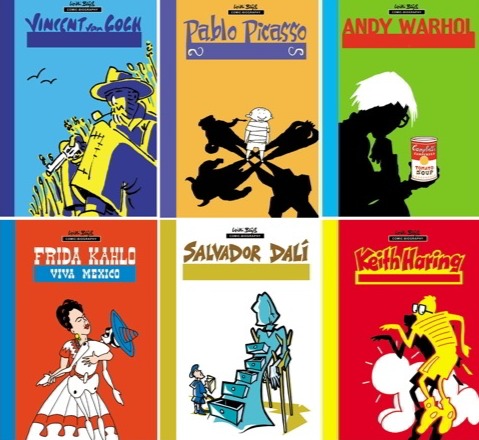

An exhibition of only six artists cannot come close to encompassing this genre. It is important to add that in Germany itself, a number of comics creators have also produced intriguing graphic biographies of artists. The most prolific by far is the Aachen-based Willy Blöß, whose compact Comic-Biographie booklets condense the stories of twenty-four artists or art movements so far, from Bosch to Beuys via Grosz, Hopper, Warhol and Hockney, into 32 colour pages drawn in a variety of styles, typically with quite extensive text narration. Blöß was awarded the 2012 Deutscher Biografiepreis for his innovative series and a number were optioned by Bluewater Comics in America for release as comic books in English.

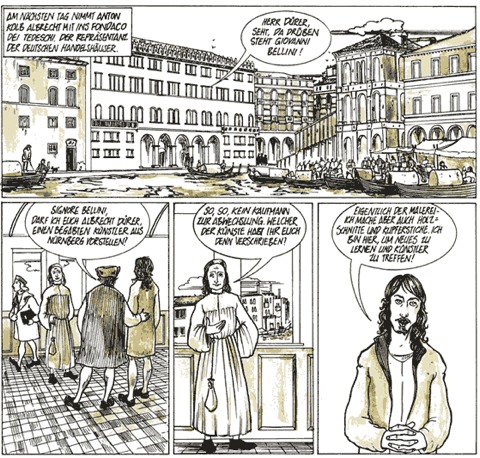

In addition, for Prestel Junior children’s books, Barbara Yelin has chronicled the lives of Albrecht Dürer (above) and Vincent Van Gogh, while Mona Horncastle has presented Gustav Klimt (with Vitali P. Konstantinov) and Claude Monet (with Matthias Lehmann), all in 48-page colour ‘Kunst-Comics’ albums. Albrecht Dürer is also the subject of a graphic biography self-published by Berlin-based cartoonist and storyboard artist Ingrid Sabisch (below).

Commentary and Photos from the Exhibition Opening:

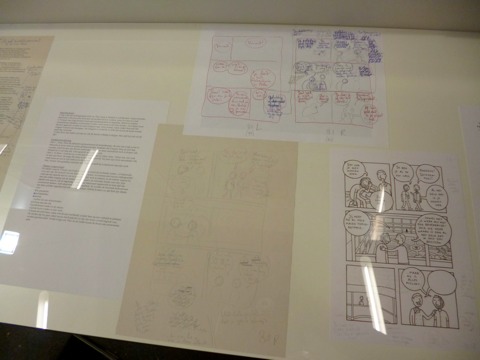

Reflecting the studio setting of the six international graphic novelists selected by the Kunstverein Ludwigsburg, the ‘Kunst-Comics’ exhibition installs their artworks both on the wall as framed originals or digital prints, and across a desk-level horizontal surface to show their preparatory layouts, scripts and research, with an angle-poise lamp shining overhead. So for example, Coste presents his photos and sketches based on his visit to the prison where Schiele was jailed. Opposite each of these ‘bays’ are two banners, one a brief biography of the artist with a reproduction of a key work by them on view in the Stadtsgalerie Stuttgart, the other a bio of each comics artist. Beneath these are benches where visitors can sit and browse both books about the artists and their graphic biographies.

Modest yet carefully chosen and elegantly presented, this exhibition has the potential to reach a very broad public. The most gratifying comment I received after my introductory speech at the opening came from one senior visitor, a lady who was beaming with delight, as she said to me, “Sie haben meine Augen öffnen!” - “You have opened my eyes!”

Barbara Stok, Larks Fiske & Typex

Steffen Kverneland’s section

Visitors to Kverneland’s section

Biography banners of the artists & their biographers

Typex in his section

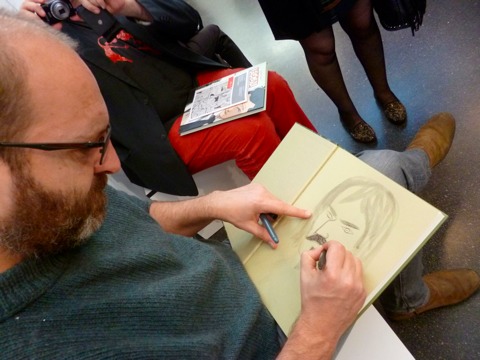

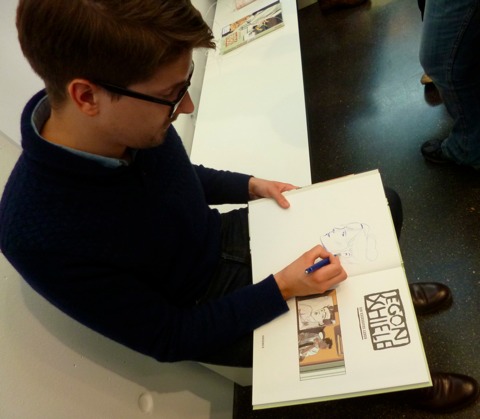

Christophe Gaultier signing his book

Barbara Stok’s VIncent scripts & sketches

Xavier Coste’s section

Xavier Coste signing his book

With thanks to Heiner Lünstedt for additional information.