Schuiten & Peeters:

Cities Of The Fantastic

In Belgium people have a nickname for the urban planners’ disease: ‘Bruxellisation’. Take a stroll beyond Brussels’ medieval marketplace and you’ll quickly understand why. In their eagerness to create a modernised capital fit for the Euro-bureaucrats, the city’s authorities permitted the wholesale demolition of many historic sites and in their place blighted the centre with soulless towering office blocks. How can planners and architects become so removed from reality, that they forget about the effects that their environments have on the human beings who have to live in them?

Born in Brussels to a family of architects, Francois Schuiten (pronounced ‘Frahn-SOOAH SKOYten’) grew up with the effects of ‘Bruxellisation’ all around him. That might explain why, although academically trained as an architect, he switched to studying another profession, comics. Belgium, birthplace of Tintin, Lucky Luke and many more all-ages favourites, boasts the most ‘bande dessinee’ creators per capita of any nation. As a student Schuiten had witnessed the post-1968 Francophone revolution of B.D. magazines and albums for adults. What better outlets in which to unleash his grandest designs, not left unbuilt as architectural impossibilities, but realised in ravishing, meticulous sequential art for everyone to explore?

Barely 21, Schuiten had his first 8-page science fiction fable ‘Shells’ snapped up by Metal Hurlant in 1977 and swiftly translated in its American counterpart, Heavy Metal. His further fantasies appeared there, but it was his partnership in A Suivre in 1982 with ‘writer-technician’ Benoit Peeters, novelist, critic, Herge expert, and a friend since student days, that resulted in their joint masterwork, the Cities Of The Fantastic series.

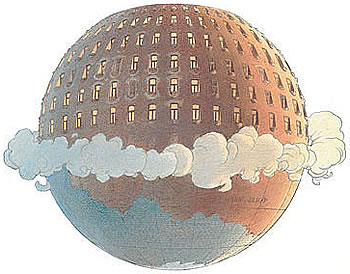

They set each new album in a different, often isolated city, rigourously ‘terraforming’ a coherent parallel world, through which, as in the best science fiction, they can allude to and comment on our own. Echoing our urban realities, their characters’ lives become dominated, even overwhelmed, by the extraordinary ‘psychetectures’ they are forced to inhabit. Building upon the imaginings of Jules Verne and the ingenuities of Jorge Luis Borges, Schuiten and Peeters construct each metropolis along distinct utopian ideals but taken to wild extremes.

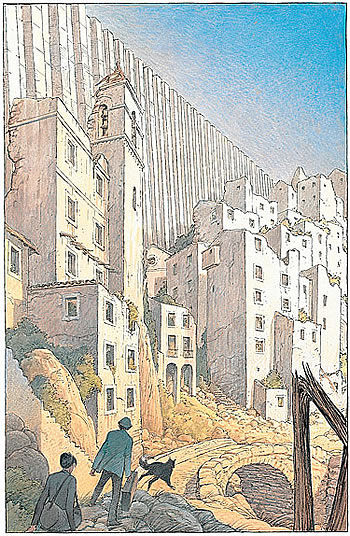

Since 1987, of the sixteen albums they have co-produced, NBM have translated five so far. In The Great Walls of Samaris, Franz is a citizen of Xhystos stifled by its Art Nouveau opulence, as lavish as Winsor McCay’s palaces in Little Nemo In Slumberland. Franz accepts a mission to investigate the mysterious Samaris, where previous scouts have vanished. He finds the walled city and its inhabitants outwardly normal, but can’t explain the unease he feels.

Finally, he breaks through a wall and discovers that all along he has been the only living person trapped within a vast mechanised stage set. He learns that Samaris, patterned on a carnivorous flower, is almost alive. To renew and expand itself, it needs to feed on an endless supply of images from people lured into her continuously moving labyrinth. Franz escapes and struggles home, only for his warnings to be ignored. In a still darker twist, Franz now see Xhystos too as a sham, but is he finally seeing the truth or is he deluded with paranoia?

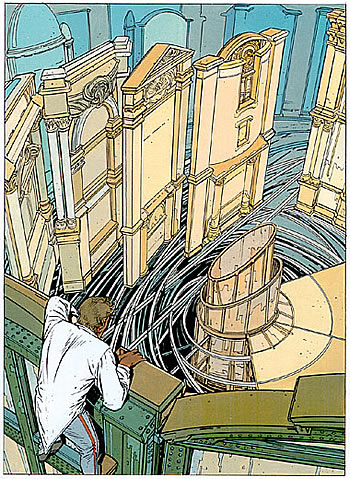

In the allegorical Fever In Urbicand in 1990, Eugen Robick, Urbicand’s self-important architect, is frustrated that his ‘regularisation’ of the north bank of the city has been left unfinished, his plans resembling the fascist monumentalism of Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer. On his desk sits a metal lattice cube, recently unearthed, which bafflingly proceeds to replicate and expand exponentially, passing harmlessly through walls and flesh. It’s a humbling lesson for Robick when it grows big enough to bridge both banks and finally connect Urbicand’s divided halves. The Tower in 1993 centres on Giovanni Battista, a lone caretaker of one section of a huge Babel-like structure. Without contact for ages, he ventures down to the ground and becomes embroiled in the power politics behind this lofty folly.

After a gap, NBM resumed the series in 2002 with Brusel, a thinly disguised retro-version of their native Brussels, which also falls foul of callous redevelopment in the name of progress. Though their satire is more pointedly topical here, it strikes universal chords. There’s broader humour too, especially in the hospital, supposedly a model of technology, which proves alarmingly inefficient.

In January 2003, as stars of the 30th Angouleme Comics Festival, Schuiten and Peeters hit a new peak in part one of The Invisible Frontier, their oblique comment on the break-up of Yugoslavia. While an apprentice cartographer is caught up in a ruler’s ambitions to re-draw his country’s territories, he falls for a mystery woman with a map drawn onto her body.

Make these elegant, fascinating, sensual Cities Of The Fantastic your next destination.

The original version of this article appeared in 2003 in the pages of Comics International, the UK’s leading magazine about comics.