Moomin:

Tove Jansson's Dreamworld

Bless my tail! Between 2 March and 29 August, 2010, The Belgian Comic Strip Centre in Brussels hosts an exhibition I’ve curated devoted to Moomin: Tove Jansson’s Dreamworld. I went over last Monday to help Exhibitions Director Didier Geirnaert and his team with the final stages and media interviews before the opening on the Tuesday night. During the champagne reception, the Finnish Ambassador welcomed us all, followed by a choir of Finnish children who sang the Moomin song, in Finnish and then in Swedish, and cut a ribbon to declare the exhibition officially open. This was a dream project for me, with a special emphasis on Tove Jansson’s work in comics, showing examples of her delicate pencil sketches, many of them highly detailed, and some of her completed ink drawings for the first 1947-1948 Moomin strips. The extra attractions are a dozen finished ink “synopsis” drawings never before shown to the public for her 1950s Evening News Moomin strips.

The exhibition would never have been possible without the generous help of Sophia Jansson and her colleagues at Moomin Characters in Helsinki, Kalle Jamsen and everyone at the Finnish Cultural Institute in Brussels, Elina Bonelius and Eija Kangasmäki at the Tove Jansson Archives in Moominvalley, Tampere, and my good friend Juhani Tolvanen whose fascinating history of the Moomin strips is shortly to be published in English by Drawn & Quarterly. I thought I would share my English texts for the exhibition here and include a few photos to give you some flavour of what is on show. But this cannot beat experiencing the exhibition for yourself. I hope you will have the chance to visit it over the coming months.

Exhibitions Director Didier Geirnaert (left)

with Moomin exhibition curator Paul Gravett.

Welcome! Step on board and let’s set sail on a voyage of discovery into the Dreamworld of the Moomins. You may be familiar with these small, white, forest-dwelling creatures, who look a bit like furry hippos, and are handy with boats. The Moomins were created in 1945, 65 years ago this year, by Tove Jansson (1914-2001), a Finnish artist and writer from the country’s Swedish-speaking community. Perhaps you know them best from the various animated adaptations on television or in feature-length movies such as Muumi ja vaarallinen juhannus (‘Moomin and Midsummer Madness’). And of course, the Moomins are also still much loved thanks to Jansson’s perennial illustrated novels and picture books.

In this exhibition, you will (re-)discover these well-known versions of the Moomins. But you can also explore how Tove Jansson’s characters led a whole other life and further adventures in comics. As early as 1947, Jansson was commissioned to create a Moomin comic strip by Finland’s Ny Tid newspaper. For this she chose to adapt her second Moomin novel, Kometjakten (‘Comet in Moominland’) published in 1946. She turned it into the weekly serial Mumintrollet och jordens undergång (‘Moomin and The End of the World’) which concluded in 1948.

Even more important than this first commission are her later Moomin comic strips for Associated Newspapers in London from 1954 to 1959. For the London Evening News, she conceived 1,645 daily strips, six per week, Monday to Saturday. She told twenty-one Moomin stories in all, eight of them with help from her brother Lars, who took over the strip completely after 1959. Sadly, the London syndicate destroyed all the artworks from Tove Jansson’s 1950s comics except for one episode. Luckily, she kept many of her detailed pencil sketches and pasted them next to proofs of the finished strips, which you can see here courtesy of the Moominvalley Achives in Tampere Art Museum in Finland.

You can also enjoy some of the earliest prototypes of the Moomins from the 1930s in Jansson’s cartoons and covers for the satirical magazine Garm. And you will find some insights into Jansson herself, her family background, her personal life and some of her other creative projects. We are also grateful to Moomin Characters to be able to show in public for the very first time some of her preparatory synopses which have only recently been discovered.

Whether you remember the Moomins from your childhood or are enjoying them afresh today, we are proud to (re-)introduce this masterpiece with a timeless appeal to children and adults alike and to celebrate the artistry and imagination of this unique, visionary storyteller.

Moomin Animated Adaptations:

Moomin On Screen opens the exhibition with the familiar animated adaptations.

Moomin On Screen opens the exhibition with the familiar animated adaptations.

Over the years, there are have been several different animated versions of The Moomins made for television and movies. Two widely broadcast successes in particular stand out. Between 1977 and 1982, a Polish adaptation used felt-covered figures for a stop-motion series, for which Tove and Lars Jansson approved and contributed to the scripts. Then, starting in 1990, the Japanese-Dutch production Moomin (originally Tanoshii Muumin Ikka) was produced by Lars Jansson and Dennis Livson. However close in spirit some of these film adaptations may be, most are rather remote from Tove Jansson’s distinctive artwork.

1: Birth of a Moomin

The first appearances of Moomin

So where do the Moomin originally come from? They actually first appeared in Tove Jansson’s drawings long before she wrote and illustrated her first Moomin novel in 1945. The very first time she drew a Moomintroll was during one of the summer vacations she spent with her family from 1923 on the main island of the Pellinki archipelago, near Helsinki. Their fishing cabin had a separate outhouse toilet, whose walls they would cover with amusing magazine clippings and their comments and graffiti. During one heated debate between Tove and her younger brother Per Olov, he had written on the wall as his final word a quotation by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. Tove recalled that this “...was so impossible to argue with that my only chance was to draw the ugliest figure I could and write ‘Kant’ under it! That was the first Moomintroll!”

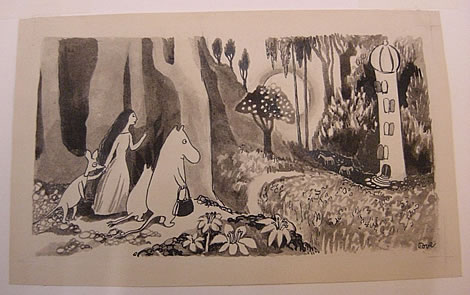

An ink and wash image from the very first Moomin book from 1945,

Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen

(‘The Little Troll and The Great Flood)

As for that peculiar name, Tove first heard it in the early 1930s while she was studying at the Art School in Stockholm and lodging in her Swedish uncle’s home. One night when she sneaked into the kitchen for a midnight snack, her uncle surprised her. “He told me that a troll lived behind the cooker. His name was Moomin and he liked to blow on the nape of people’s necks.” Perhaps she was remembering this when Tove painted this strange scene of a rather menacing black troll with glowing red eyes in 1936.

Starting at the age of only 15 in 1929, Tove became a regular contributor to the satirical monthly Garm, where her mother also worked. In a cartoon in the April 1943 issue she introduced two friendlier, long-snouted white trolls and gave one of them the name “Snork” written on his belly. From the autumn of 1944, she regularly included this creature as a signature observer and commentator in the sidelines of her cartoons and front covers. The magazine already had its own mascot, the black dog of hell in Scandinavian mythology named Garm, and now Tove Jansson had devised a mascot of her own, and a prototype for her Moomintroll books and comics to come.

2: A World of Reading

Originals by Tove Jansson from her Moomin novels and picture books.

As well as drawing and painting, Tove Jansson had always enjoyed writing and by 1944 was producing articles and several novellas. But during the dark winter days of 1939 to 1940, amid the Second World War and the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union, she had been feeling so sad, that to get rid of her sadness she found solace by creating her first story with a happy ending. Looking back in 1953, she reflected:

“In the beginning the stories about the Moomintroll were actually some kind of escapism, one was rescued into a world where everything was gentle and safe. Perhaps I sought to bring myself back to a childhood which was happy, and where the everyday and the incredible were intertwined in carefree fashion. I believe most children live in a world where the fantastic and the obvious are in equanimity, and it is that world which I have tried to reconstruct and describe to myself.”

A gouache painting from A Dangerous Journey,

out in English later this year from Sort of Books

In 1945, she went back to her forgotten manuscript and completed and illustrated it. The publisher Alfabeta then published it that year as Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (‘The Little Troll and The Great Flood’) in Swedish, the minority language in Finland. Moominmamma and Moomintroll search for “a snug warm place” and after various escapes, they are reunited with Moominpappa in the serene Moominvalley. By the end of this adventure, the foundations of the dreamworld of Moomin are already in place, as the family move in to their new home and adopt Sniff, here called simply “little creature”, as the first of numerous long-term guests.

Tove started right away in 1945 on the second book, Kometjakten (‘Comet in Moominland’), published in 1946. In all, Tove Jansson wrote and drew nine Moomin novels, culminating in Sent i november (‘Moominvalley in November’) in 1970, revising some of them many times. She also created several highly innovative Moomin picture books. Here you can see a selection of sketches and finished drawings from them, demonstrating her versatility with pen and ink, watercolour, scraperboard and other media, and her genius at evoking atmosphere and emotion.

3: First Steps into Strips

The first Moomin strips from 1947-8 in the newspaper Ny Tid.

Tove Jansson grew up reading comics in Swedish magazines and was soon making her own. In the spring of 1929, aged 14, she started drawing the adventures of two caterpillars, and she was paid to have them published in colour for seven issues from August 31st 1929 in the children’s paper Lunkentus. For these and other occasional comics, she used the old-fashioned system of putting all the narrative text beneath each panel.

What revived her interest in comics was a request in 1947 from her close friend, the left-wing intellectual Atos Wirtanen, to create a strip for his socialist newspaper Ny Tid (‘New Time’). Atos had been the inspiration for Snusmumriken (‘Snufkin’), who wore the same green hat. She decided to adapt her latest children’s book, Kometjakten (‘Comet in Moominland’), and changed its language, tone and resolution for a broader family readership, warning that it was “not suitable for very small children!”

She planned Mumintrollet och jordens undergång (‘Moomintroll and the End of the World’) on upright pages of six square panels in three rows of two. But when the 26 episodes ran on the newspaper’s children’s page, every Friday from October 3 1947 to April 2 1948, they appeared in single horizontal strips. Tove recalled, “Since at the time I hadn’t read comic strips in daily newspapers, I misunderstood most things, especially the idea of speech bubbles. Instead of speech, I wrote a sort of story under each picture.” Even so, her hand-lettering can be very expressive, changing size to convey volume, becoming more ornate when female characters speak and flying about when the Cyclone strikes. She also introduced new characters such as Tofslan och Vifslan (‘Thingumy and Bob’), based on herself and her new great love, Vivica Bandler.

Tove ended the story differently from her original novel and in rather a hurry, adding a spherical rubber lifeboat and an odd final flourish where the Moomins find their home with a pearl necklace on the roof “making the Moomin family into a millionaire family, just like that!” Ny Tid promised Tove’s return by the autumn of 1948, but instead it would be another four years before she would embark on newspaper strips again.

4: Moomin Goes Daily

A 1954 photo of Evening News vans promoting the Moomin strip in London.

Sporting a bowler hat and umbrella, English businessman Charles Sutton entered Tove Jansson’s life in early 1952 and changed it completely. From their relationship gradually developed the throughly modern and successful Moomin newspaper strip. Sutton was director of syndication for Associated Newspapers in London, publishers of the major national paper The Daily Mail and London’s Evening News. He saw how the Moomin novels, translated into English starting in 1950, were becoming critical and commercial hits in Britain and realised that they had potential as comics to syndicate nationally and internationally.

Sutton’s first proposal to Tove Jansson was for “an interesting strip cartoon, and not necessarily for children” that would use her characters “to satirise the so-called civilised way of life” and she responded enthusiastically. After more positive correspondence, Sutton came to Helsinki on May 1st 1952 and amid the Walpurgis Night festivities Tove agreed to a draft contract of seven years, until 1959. Short of cash and tired of the uncertainty of freelancing, she imagined a regular monthly salary to produce “only six comic strips a week” would leave her more time to paint and write, but this was not to be.

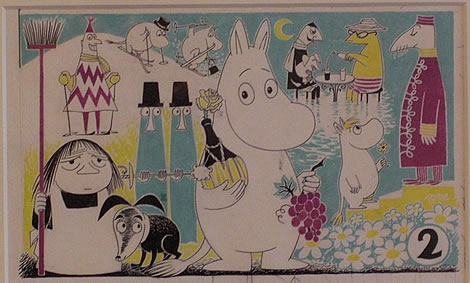

Cover art for the first Moomin strip collection in 1989.

Under Sutton’s guidance, the Moomin project underwent an unusually long and meticulous gestation. He encouraged Tove step-by-step to evolve an engaging, more sophisticated daily comic, as they wrote back and forth about storylines, techniques and characters. Time and again, its launch date was planned and then postponed. In March 1954 Tove was invited to Associated’s strip department in London for an intensive two-week course. The final results of all this careful planning premiered on Monday September 20th 1954 in The Evening News, then the biggest evening paper in the world.

Original art for the second collection of Moomin daily strips, 1989.

Far from a minor sideline, the Moomin strip is one of Tove Jansson’s great achievements, expanding her stories, settings and cast and invigorating her drawing and writing. She brings a sense of discovery to the medium, notably in her playful dividing of panels with trees, a sword, skis or a bedpost. Tragically, after so much care, Associated Newspapers later destroyed all of her original artworks; only one unsubmitted example survives. But Tove’s pencilled sketches let you examine her thinking processes and compare them with the printed proofs which she glued alongside them. With her brother Lars’ help, as her translator into English from the start and later her collaborator, Tove fulfilled her contract in 1959. By then it was a relief to hand the strip over entirely to Lars who kept it sailing until 1975.

5: Treasures Rediscovered

One of the 12 synopsis ink drawings on show for the first time.

These mysterious twelve sheets of ink drawings by Tove Jansson have recently been restored, so that they can now be exhibited for the very first time. They come from a selection of around forty such sheets discovered among her effects after she passed away in 2001. What were they for? They are labelled as “synopses” and consist of characters, settings, props and scenes for eight different comic strip stories published between 1955 and 1958 in The Evening News. The fact that Tove drew them on thin, fragile tracing paper, and not on the high quality board which she used for her finished strip artworks to be sent to London, and the fact that they survived in her Helsinki studio, suggest that she made them for her own personal purposes to prepare for each new episode.

Look carefully and these rare items reveal some secrets. Their numbers let us see the different order in which the stories were originally conceived, and ideas which never made it into the final comics, such as the rhinoceros with an orange on his horn. Many other drawings here were redrawn exactly, line-for-line, for the final comics. For example, in Episode 3. High Life, the poolside portrait of Little Audrey Glamour, a caricature of Audrey Hepburn, with dog and swimmers appeared complete in the 15th strip of the retitled story Moomin on the Riviera.

This process is especially useful for Tove Jansson to work out different outfits for her cast, for example designing Moomin dressed up in his leopard-spotted Tarzan costume or cowboy hat, boots and gun. She also employed it to develop and define fresh characters, so here you can spot the glowing Martians or the vamp Miss La Goona, her strongman suitor Emeraldo and her swimming, flower-eating horse.

For better or worse, the demands of creating her daily strips, six every week, sometimes led Tove to put her characters into surprising predicaments unlike anything they had experienced in the novels. Who would have thought that the Moomins would encounter jungle animals, American cowboys or a flying saucer from Mars? Unusually, one adventure, Moomin on the Riviera, was based on Tove’s holiday on the Côte d’Azur with her mother, who like Moominmamma got herself trapped inside a deckchair!

6: The World of Tove Jansson

As part of The World of Tove Jansson section,

visitors can watch the Moomin Memories documentary.

What sort of person could have dreamt up such a universally meaningful world as Moomin? It was all the dream of one very creative, perceptive woman, Tove Jansson, and its true source was her unique personal experience. She was born on August 9th 1914, a Leo, in Helsinki and was predestined to be an artist and a bohemian. After all, she was raised in an artistic household in the capital’s Jugendstil district by her father, the sculptor Viktor Jansson, and her mother, the illustrator Signe Hammarsten-Jansson.

Drawing from an early age, Tove became as close to nature as to art. Every May to September, she reveled in the family’s boating trips to numerous islands in the Pellinki archipelago, inventing adventure stories about them in her diaries. Her affinity with island life would fill her writings and call her back there as an adult.

Although she became best known as an author, painting was always important to her, having studied from the age of 16 to 24 in Stockholm, Helsinki and Paris. She held several exhibitions and was commissioned to paint frescos and murals. She also joined her mother as a regular contributor to the satirical magazine Garm, drawing every cover from 1944 to 1953. Mixing in Finland’s vibrant Modernist and Socialist circles, she met Atos Wirtanen, at one stage her fiancé. Together they had planned to buy a Finnish philospher’s villa in Morocco and Tove envisaged converting it into an artists’ sanctuary, complete with a tower topped by a hanging garden. This unrealised retreat anticipates the magic of Moominvalley and her own eventual home built on a Pellinki island called Klovharu with her partner, the graphic artist Tuulikki Pietilä.

After the death of her beloved mother, the model for Moominmamma, in 1970, Tove wrote one last Moomin book, Sent in november (‘Moominvalley in November’), and from then on concentrated on her writing for adults. To the end in 2001, she understood the promise of an idyllic community, a place of both security and freedom, because she herself belonged to a number of minorities. Like her parents, she was one of only six per cent of Finns whose first language is Swedish. She was also a discreet lesbian, an unconventional artist, writer and creator of comics, and a free-spirited woman. Her special empathy infused Moomin, and so much of what she created, with a warm, wise humour and a gentle appeal for the acceptance, even celebration, of individuality and spontaneity.

7: Beyond the Moomins

Tove Jansson’s cover for Alice in Wonderland.

In 1983, at the age of 69, Tove Jansson insisted to the American professor of English Nancy Huse that “The artist doesn’t retire!” Tove proved this by living a rich and diverse creative lifetime which spanned from her childhood and her first paid publications made at the age of 14 through to her last works in her Eighties. She has become reknowned worldwide for her varied Moomin oeuvre, which also features her cointributions to a number of Moomin-themed plays and her collaboration with her partner Tuulikki Pietilä and others on forty-one scale models of three-dimensional tableaux based on scenes from the stories,

In addition, Tove produced many paintings including self-portraits and more abstract compositions, and illustrations for books by other authors. Among these projects shown here are her interpretations for Swedish translations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and The Hunting of the Snark and J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, classics of imaginative fantasy for children and adults which relate to her own works.

Tove Jansson’s cover for Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

In 1966, she won the Hans Christian Andersen Award in recognition of her contributions to children’s literature. She has also been increasingly acclaimed for her adult novels, short stories and memoirs, such as Sommarboken (‘The Summer Book’) and Rent Spel (‘Fair Play’). Her 1974 novel Solstaden (‘Sun City’), whose striking cover is shown here, deals with the ageing owner and assorted residents of a rest home in Florida and the younger staff who provide for them. With parallels to the theme of tolerance in Moomin, she charts how contrasting individuals come to form a subtly supportive pretend family.

Tove Jansson & Tuulikki Pietilä

Working together on the Moomin models and tableaux.

In her Seventies, Tove Jansson realised that her original drawings and the Moomin models needed to be preserved for the future. She began donating them to the Tampere Art Museum in Finland, which today houses her archives of around 2,000 items and the Moominvalley Museum, whose exhibitions have been visited by over a million people since its opening in 1987.

In 1955, she reflected: “Duty and pleasure are a long story for me, constantly in question, and gradually I have come to a strange and quite private result. The only honest thing is pleasure, the wish, the joy - and nothing that I have forced myself into has been of joy for my surroundings.” Tove Jansson found joy in creativity and in life and she continues to give joy to everyone who enters her world.

All exhibition photos © Peter Stanbury