Curt Swan:

A Superman Walked Among Us

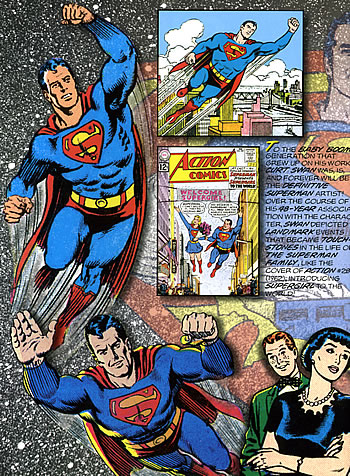

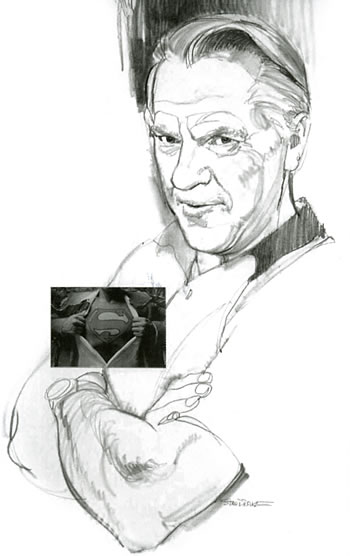

Once, a Superman walked among us. From the testimonies in Curt Swan: A Life In Comics it seems I am not the only child of the Sixties who believes that it was Curt Swan (1920-1996), more than any other artist, who brought out the man in the Man of Tomorrow. Swan’s artwork contributed hugely to making Krypton’s last son in exile, the alien in our midst, into someone like us, who would think and feel as well as act, who was approachable, big-hearted, considerate, maybe physically superpowerful yet gentle, noble yet subtly tragic. Under Swan’s sensitive pencil, Superman became as human as the rest of us, and won not just our awe and admiration, but our affection and sympathy. In Eddy Zeno’s lovingly compiled tribute (a companion to Cardy, Foster, Infantino and Simon in the series of essential Vanguard Career Retrospectives), Curt Swan, always the modest, hard-working craftsman, finally gets some of the praise he deserves from family, writers, editors, inkers, fans, bosses and army, golfing and comics friends for his nearly fifty years of artwork for the Superman family of comic books, from his first attributed one-off story in Superman #51 in March-April 1948 to his five pages published posthumously in the 1996 Superman: The Wedding Album.

Before and after Swan, Superman‘s physique and facial appearance have gone through many transformations over the years and are changing still. His co-creators, writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, were the first to conjure Superman into four-color life. Shuster gave him those wide, sweeping eyebrows, that steely squint of determination, that compact, squat body and massive chest. To meet the escalating demand for new material, both for the comic books and for the daily and Sunday newspaper strips that soon followed, Siegel and Shuster in Cleveland financed a studio of anonymous assistants to follow Shuster’s style. After Jerry and Joe’s lawsuit in 1947 against DC, or National as it was then known, forced them both to abandon their creation, their assistants swiftly filled their shoes.

One of them, Wayne Boring, had already begun working directly for DC and developed a distinct styling that supplanted Shuster’s for several years from the early Fifties. As editor Mort Weisinger oversaw the rapid expansion of the Superman mythology with Otto Binder and other writers, Boring’s bravura brushwork defined many of its key elements and made Superman look more powerful and imposing, now standing a heroic nine heads tall, and brought a fresh realism, a sleek sci-fi vision and a greater seriousness of tone. Boring’s Superman is much loved by many, but to my boyhood eyes could appear awkward and mannequin-like at times, striking poses and flying stiff-limbed, with the barrel-shaped torso of a weightlifter, as broad around the waist as it was around the chest. His face showed more varied and less cartoonish expressions than before but was usually set firm by his large, prominent jaw.

More naturalistic than Boring’s interpretation were the Superman covers and daily strips drawn by Win Mortimer. Zeno (his surname even sounds like a Sixties Superman alien!) explains that when Mortimer left DC in 1956 for a time to concentrate on his own strip David Crane, this paved the way for Swan, his ideal successor, to rise to the position of the principal Superman artist by the early Sixties. Zeno charts this ascendancy in a thorough 45-page career overview that opens the book, starting in 1945 with Swan’s initial connection to DC via his army buddy, DC writer Eddie ‘France’ Herron, with whom he had worked at the Stars & Stripes newspaper. Swan’s first DC assignments published from 1946 were on Simon and Kirby’s kid gangs Boy Commandos and Newsboy Legion. These were followed by SF back-up Tommy Tomorrow from 1948, inked by John Fischetti, another of Swan’s pals from his army days, who went on win a Pulitzer prize for his political cartooning, and the radio and TV crime drama Gangbusters. Swan was proving himself a versatile and valuable addition to DC’s roster.

Intriguingly, Zeno reveals that, though uncredited and unsigned, Swan’s early work can sometimes be identified thanks to his signature drawing of hands, especially those with the middle fingers together. From such clues, it seems Swan began pencilling Superboy from the fifth issue in 1949, but apart from the 1948 Superman one-off previously mentioned and stories in Superman #73 and #76, Swan always felt that his first meaningful Superman assignment was the one-shot Three-Dimension Adventures of Superman in 1953, and that his breakthrough came with the assignment to Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen, given his own title from 1954. Following Win Mortimer’s departure from DC, Swan took on his roles, drawing the daily Superman strip from June 18, 1956 through November 12, 1960 (a body of work that cries out to be properly reprinted in book form), and a year later becoming the cover penciller for the entire Superman family of comic books. As Zeno concludes, "It can be argued that history also needs to be rewritten in terms of when he became a primary Superman artist… Curt attained that status by 1957, not 1962, as is generally noted."

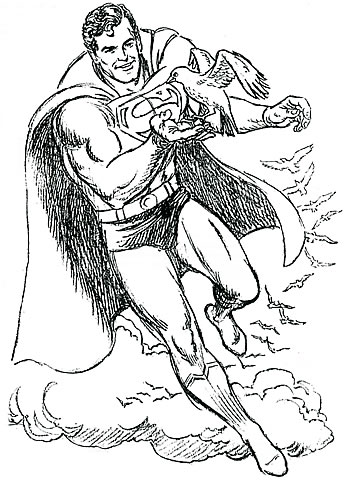

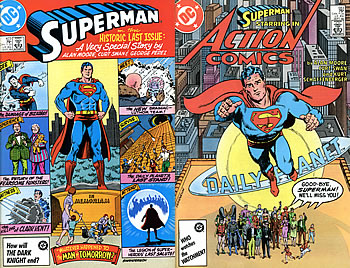

It was 1962, however, which Zeno identifies as the start of no less than four ‘zeniths’ through Swan’s career. The three years from 1962 to 1964 encompass the classic two- and three-part novels edited by Weisinger and inked by George Klein such as the poignant Imaginary Tales, The Death of Superman written by Jerry Siegel and The Amazing Story of Superman-Red and Superman-Blue written by Leo Dorfman. According to Zeno, Swan’s second zenith spans the ‘Swanderson’ years, teaming him with another of his greatest inkers, Murphy Anderson, on the landmark 1971 revamp of the hero under editor Julie Schwartz and new young writers Denny O’Neill (a surprising omission from the book’s interviewees), Elliott S! Maggin and Len Wein, with Cary Bates. The ‘Swanderson’ team’s characterful drawings of Superman chomping down a lump of deactivated Green Kryptonite served as a satirical farewell, at least for a time, to that overused plot device. The third zenith reflects his mature late period around the time of the touching two-issue ‘last Superman story’ written by Alan Moore in 1986 that drew to a close the Silver Age firmament wiped away for John Byrne’s reinvention. Zeno perceives Swan’s fourth zenith covering his private commissions from the mid-Eighties, several of which are shown here, which bloomed as his published work dwindled until his death in 1996. On these he would ink his own pencils, then color them too, finally returning to pencilling alone but with a still greater mastery of shading and detail.

Swan was famously unpretentious and unassuming; the last thing he would want to go on about was himself and his art. So instead at the heart of this book are the 100 pages of interviews, commentaries and correspondence from thirty seven of Swan’s many admirers, from army cohort Andy Rooney, editor Julius Schwartz and Legion of Super-Heroes writer Jim Shooter to Swan’s favorite inker Al Williamson and writer-artists Dan Jurgens and John Byrne. Their cumulative effect is to get to the true nature of this man and this artist. Zeno has talked to Swan’s ex-wife, his son and two daughters and learnt how he would always give his family time and attention while working from home and how his flexible approach, averaging three days on and four days off, playing golf if the weather was fine or helping his children with their homework, sometimes forced him to work for long stretches into the small hours to meet his deadlines, puffing on his cigarettes. The kids always knew they had to be very quiet in the house the morning after. We learn that the artwork didn’t always come easily to him; there would be dry periods, so at other times, when the drawing was flowing, he would push himself harder than ever. Amazingly, apart from a few months of night classes under the G.I. Bill, Swan was entirely self-taught from studying anatomy books and applying himself.

When it came to his original artwork, it turns out that, like many comic book journeymen of his time, Swan was pretty cavalier about keeping any for himself He had no problem that much of it used to be given away to readers as letter column prizes and gave a lot of it away himself for charitable causes. Swan might come into the city and pencil two or three covers in a day at the offices for Weisinger, who ‘paid’ readers like Cary Bates, future DC writer, for their arresting cover images, springboards for stories, not with money but with the original cover artwork. But one story meant a lot to him, one of the few he both pencilled and inked. He made a point of giving everyone in the family a page from the story I Flew With Superman from Superman Annual #9, 1983, in which Swan himself appears and helps the Man of Steel solve a case. Family tales like these tell us so much.

Swan speaks for himself here as well, in three short concluding interviews with Raul Wrona, one in person from 1986, two by phone from 1996. It’s here that Swan confirms that Weisinger’s editorial bullying forced him to quit comics around 1951. "I was getting terrible migraine headaches and had these verbal battles with Mort. So it was emotional, physical. It just drained me and I thought I’d better get out of here before I go whacko." He was soon back, though, because the advertising work didn’t pay enough to support his family. Zeno notes, "The headaches went away after he gained Weisinger’s respect by standing up to him." Swan also tried pitching a strip for syndication around 1954, Yellow Hair, about a blond boy raised by Native Americans, four samples of which are shown here, but it never sold. Of course, there were other times when Swan could get frustrated with DC, and later he was offered deals to switch to Marvel, but he stayed loyal to the end as the benefits were good and the work steady. Or at least it was, until his style went out of fashion.

In 1967 Boring had been unceremoniously fired by Weisinger without notice; luckily the next day Boring contacted Hal Foster and started as his assistant on Prince Valiant. Swan was never fired, but he was taken off the monthly Superman books for 1986’s relaunch and for a time, for too long, towards the end, his assignments were drying up. Writer Roger Stern recalls a dinner in 1988, one of the first group ‘Super-Summits’ with Mike Carlin, Jerry Ordway, George Pérez, Kerry Gamill, and Swan was there too, enjoying being asked for the first time to give his input. Stern comments, "To have this guy who so understood how the character moved and lived and had ideas about it. And they never used it. They never tapped into that resource. It just breaks your heart." As Swan put it, "I’d sit in a room somewhere, they’d send me a script and I’d draw it." Nevertheless, Swan did enjoy some ‘swan songs’ including his ‘pseudo-Sunday page’ Superman centre spreads for Action Comics Weekly, his runs on Aquaman and back on Superboy again, and prestige specials like Superman: The Earth Stealers.

To me, one of the most moving tributes comes from Elliott S! Maggin, barely twenty in 1971 when he started scripting Superman for Swan, thirty years his senior. As he puts it, "divide and conquer was a widely respected management technique", and Maggin avoided Swan after he was told that Swan wanted to "throttle" him for the elaborate digressions in his scripts. But in the mid-Eighties, towards the end of their time working apart, they got to hang out over "a little libation", and they found that, "We were both philosophical products of the message we spent a career delivering to the hero-worshippers of the world. We both believed in truth, justice and the American way: a personal torah. It was good finally to learn that we had so much in common when finally we gave each other the space to reveal it". So they did get to connect, but some fifteen years after their initial collaboration, so much later than was necessary. And in a typically perceptive interview, Alan Moore muses about Swan: "I’d like to have asked him how much he identified with Superman, how much of himself he put in there. I feel that he probably did on some private level; that there was some sort of a moral strength that he aspired to, that he drew into those figures. Something almost indefinable, but some essence of himself…" I am sure Moore is right; I can see something of Superman in every photo of Swan in this book and in so many descriptions of the depth and decency of Swan’s character.

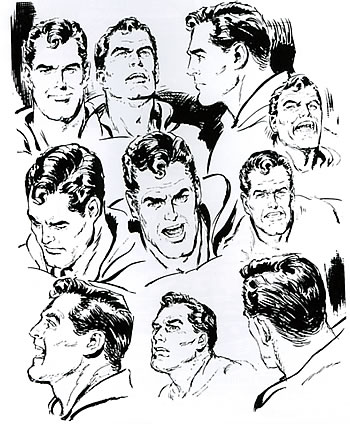

Throughout this book are some genuine insights into Swan’s understated but sophisticated approach to comic book art. In his sixteen-page colour Gallery, writer and designer Arlen Schumer highlights Swan’s greatest characters and strengths. On one spread of faces, he praises his depictions of "the spectrum of human emotion, from agony to anger, mournful to mirthful". On another he shows examples of his landscapes "whose melancholy stillness evoked those of early 20th century surrealist painter Giorgio de Chirico", while another underlines his point about Superboy growing up in Smallville having an "unmistakable Rockwellian appeal". Fittingly his last page compiles some of the recurrent Superman imagery of statues, monuments and memorials, which "show an artist whose style mirrored his name, that of a swan itself, graceful and dignified, yet strong and resolute, permeated with an air of solemnity." Schumer has become quite brilliant at distilling and displaying the fundamentals of a comic artist. In summation in the closing pages, Zeno joins Schumer, Wrona and Stern in observing that Swan’s striving for realism, his inspiration from the classical illustrators, the appealing clarity, warmth and truly American subjects of his drawing, make him ‘the Norman Rockwell of the Comics’ and like Rockwell he is overdue for far greater appreciation. To that end, this book itself is a monument to the grace and dignity of Swan’s work and life.

The original version of this article appeared in 2002 in the pages of Comic Book Marketplace.