Comica Argentina:

A Rich Culture Of Cartoons & Comics

You may not realise it, but if you enjoy great comics and cartoons, then you probably love at least one Argentinian artist, whether it’s the colourful pantomime comedies of Mordillo, the dazzling superheroics of Juan Bobillo or the late Carlos Meglia, or the gritty elegance of Eduardo Risso. Comica Argentina grew out of a moment of inspiration last year from my good friend and Argentinian cartoonist Sylvia Libedinsky who suggested that we set up an exhibition and events about Argentinian comic art in London to coincide with the bicentennial this year of Argentina’s independence from Spain in 1810.

My passion for Argentinian comics and cartoons goes back a long way. Unknown to me, when I was a kid reading Kelly’s Eye, Galaxus, Janus Stark and other classic British adventure comics of the 1960s, I was transported by the moody dynamism of artist Solano Lopez. Without knowing they were from Argentina, I grew up also loving the artwork of Bruno Premiani and later José Garcia-Lopez for DC Comics and still more Argentinian talents published across Europe.

It’s no coincidence that one of the first, and at 20 pages the longest ever, of the translated stories in our 19 issues of Escape magazine was the powerful fifth Joe’s Bar episode by Muñoz & Sampayo. Peter Stanbury and I admired their work so much, we blew up an image from it in stark black and white on the front cover of the tenth Escape, the first squarebound issue from Titan Books. I will never forget my visit to Rio de Janeiro’s first Comics Biennale in 1991, when I was lucky enough to meet both Solano Lopez and Alberto Breccia at a gallery exhibition of their original pages.

Within a year of starting at The Cartoon Art Trust, I worked with Claudio Rojo, the Cultural Attaché from the Embassy of the Argentine Republic, in co-operation with the International Cartoon Festival Knokke-Heist, Belgium, to stage a major cartoon exhibition of El Humor Grafico Argentino. This was held from August 23 to September 24 1993 at the National Museum of Cartoon Art in its impressive initial temporary premises in Carriage Row, Eversholt Street, London NW1. We presented stunning framed originals from an alphabet of humorous geniuses: Molina Campos, Caloi, Crist, Fati, Fontanarossa, Grondona White, Killian, Limura, Mordillo, Nine, Oski, Quino, Redondo, Rep, Stein, Tabaré and Viuti with special Argentinian London-based guests Oscar Grillo and Oscar Zarate. Amazingly, seventeen years later, Claudio Rojo, now Consul General, came last Thursday evening to the private view for the Comica Argentina exhibition and kindly gave me one of the flyers and invitations he had kept from that historic show.

For Comica Argentina, Sylvia Libedinsky and I have chosen twenty fascinating and diverse cartoonists and comics creators, each spotlighted with their own A1-sized digitally-printed poster strikingly designed by Peter Stanbury to showcase a range of their work. The show runs till June 25th in the library gallery at Canning House, 2 Belgrave Square, close to Hyde Park Corner tube. Admission is free and the opening hours are Monday to Friday, 2-6pm. In many ways, this modest print-only show stands as a pilot for what must eventually happen, a substantial exhibition including originals and encompassing many more of the greats from the past and present.

Until then, our exhibition will move on to King’s Place, home of The Guardian and Observer newspapers near King’s cross Station, from July 1st to 5th. There will be three events there alongside the exhibition. I will give an illustrated lecture on the History of Argentinian Comic Art on Friday July 2nd from 6.30pm, and will interview Oscar Grillo and Gabriele Zucchelli on Sunday July 4th from 6pm. There is also a screening of Zucchelli’s documentary film about the making of the world’s first animated feature-length movie El Apostol on Saturday July 3rd from 6.30pm. Be sure to book tickets for these special presentations. Muchas gracias to all of the artists, the collectors, notably Diego Agrimbau, Shane Glines from cartoonretro.com, Oscar Grillo, David Roach, Oscar Zarate and especially Thomas Dassance from the Viñetas Sueltas Festival in Buenos Aires. To whet your appetite, here are some of the texts written by Sylvia and me for the exhibition and a few example images. Don’t miss seeing the real thing for yourself and discovering even more of Argentina’s rich culture of cartoons and comics.

Welcome to Comica Argentina! The familiar name for comics in Argentina is historietas or ‘little stories’, but these stories have had a huge impact on readers and their society and culture. The story behind this popular medium is also enormous, so this modest exhibition does not attempt to be comprehensive. Instead, it highlights a number of founding figures and significant innovators. Some of these arrived from Europe or elsewhere, while others have left Argentina and found international acclaim abroad.

In the bicentennial year of this great country’s independence, Comica Argentina hopes to show how turbulent history and ebullient creativity come together through the arts of cartoons, caricatures, strips, comics, graphic novels and webcomics. From their 19th century origins to their 21st century innovations, this exhibition demonstrates how the works of several major cartoonists recorded the moods and fantasies of a nation and build into a chronicle of their ever-changing times.

Under democracies and dictatorships, Argentinian creators of cartoons and comics have continually reflected and affected the spirit of their homeland through humour and adventure, fantasy and realism. The medium developed from early social cartoon prints and political satires and caricatures to encompass short strips in general-interest family magazines, later in similar titles for children, before arriving in newspapers and then in periodicals devoted entirely to comics. Satirical cartoon magazines from Rico Tipo to Tia Vicenta also flourished attracting adult readers, while more realistically drawn adventure and fantasy genres emerged in Misterix, Hora Cero, Frontera and others. By the early 1950s, comics were selling 165 million copies per year, nearly half of everything being read in Argentina.

Today, in the age of the internet and graphic novel, a new generation of creators, with noticeably many more women creators, is emerging though webcomics and a bustling small press scene. Comica Argentina concludes by presenting a few artists from today’s cutting-edge of historietas. Their ‘little stories’ are continuing Argentina’s tradition as truly one of the greatest producers of cartoons and comics in the world.

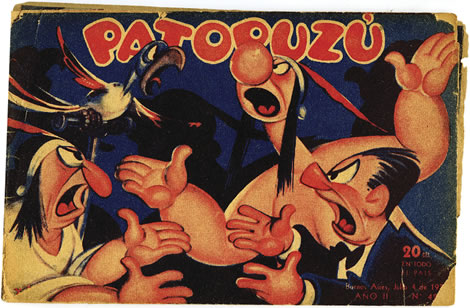

Dante Quinterno

Never one for self-publicity, Dante Quinterno (1909-2003) became Argentina’s most famous comic artist of his day in newspaper strips and his own magazines, thanks in large part to his wealthy, super-strong indigenous chieftain from Patagonia, Patorozú. He debuted under another name on October 19th 1928 in a supporting role when he was adopted by the lead character in Quinterno’s newspaper strip Las aventuras de Don Gil Contento. Re-named Patorozú, after the herbal candy ‘pasta de oruzú, the big-hearted Indian with his distinctive dialect took over the daily strip from 1931. Other hit comics were Don Fierro (originally Don Fermin from 1926), a tyrant at work but hen-pecked at home, and the fun-loving playboy Isidoro. Quinterno set up his own business empire in 1935 to syndicate his strips, run a studio and publish weekly magazines starring his characters, including Patorozú from 1936 and junior spin-off Patoruzito from 1945. Learning from an American trip to the Disney and Fleischer Brothers studios, he adapted Patorozú into the country’s first modern colour animated films. His example directly inspired the Dutch master Marten Toonder, visiting Buenos Aires aged 19 in 1931, to take up cartooning. Frenchman René Goscinny grew up in Argentina and some see a resemblance between his co-creations, Asterix and Obelix, and Patorozú and his oversized baby brother Upa. A Quinterno theme park devoted to his characters opened in 2009.

Cover of Patorozú Weekly, 4 July 1936

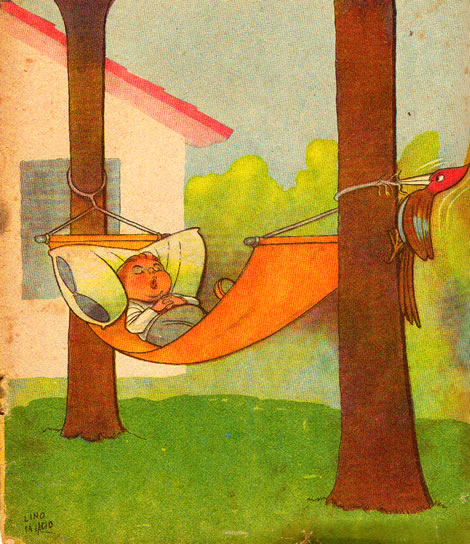

Lino Palacio

Lino Palacio Calandrelli (1903-1984) graduated in architecure and initiated his career as a caricaturist under the pseudonym ‘Flax’. In the Thirties, Palacio began publishing in the magazine Caras y Caretas. With the book Historia de la Guerra in 1942, published worldwide, he created as the only chronicle of World War II told entirely in caricatures. For a long time, he was also the cover designer of the children’s magazine Billiken. His most popular comic creations included Ramona for the daily La Opinión, Don Fulgencio for La Prensa in 1932, Do&ntild;a Tremebunda and Tripudio. He created his most famous character Avivato in 1946, who was spun off into his own magazine. Palacio was forced to stop publishing it by the Videla dictatorship in 1978, the year of the World Cup when journalists and visitors were coming to Argentina, on the grounds that depicting such a dishonest character would undermine the country’s reputation. Palacio’s work can be difficult to identify because he used different pen-names and was widely imitated, including by his daughter Cecilia and his son under the pen-name ‘Faruk’ who continued many of his characters.

Original art by Lino Palacio for cover of Billiken, 24 March 1958

Guillermo Divito

By the age of only 15, Guillermo (Willy) Divito (1914-1969) was already a professional cartoonist for newspapers, first for Noticias Gráficas, and then for La Razón. In 1931 he joined Paginas de Columba and later worked with Dante Quinterno producing such characters as Oscar Dientes de Leche published in the comic magazine Patoruzu. In 1944, Divito founded the humor magazine Rico Tipo. His creations included Bombolo, Pochita Morfoni, Fulmine and his most popular works Fallutelli and El Doctor Merengue. He owes most of his fame to the grace and style with which he depicted the female figure. His famous “Chicas,” tall and luscious beauties with narrow waists and generous bosoms found fame beyond Argentina’s borders. In 1947, Time magazine reported that ‘for women workers in Buenos Aires, Willy Divito is still more of a style authority that Christian Dior’. At its peak, Rico Tipo reached a circulation of 200,000 copies and published the best in Argentine humour, notably the talented Oscar Conti or Oski. Divito was a popular, refined bachelor, a bon vivant and an astute editor.

Divito’s cover for Rico Tipo 438, 27 May 1953

Oski

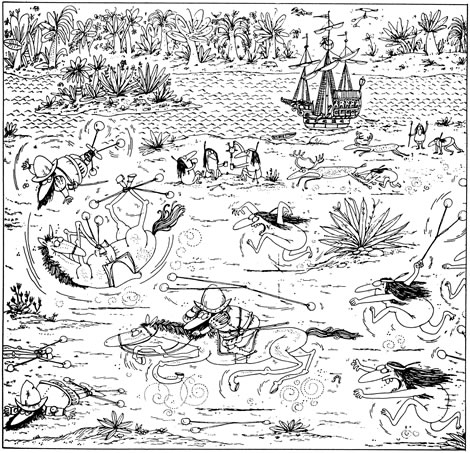

Oski is the pen-name of Oscar Esteban Conti (1914-1979), who was nicknamed ‘El Maestro” by his fellow cartoonists who recognised his exceptional artistic talent and erudition. In 1944 he illustrated Versos y Notisias, written by Carlos Warnes (alias César Bruto), a weekly satire of current events in the magazine Rico Tipo, where Oski’s drawings or ‘fotoskis’ were used instead of photographs. Oski and Bruto developed a symbiotic creative relationship in works like in La Vera Historia de Indias and El Pequeño Brutoski Ilustrado. His work brought him to the attention of Jean-Paul Sartre, who commissioned Oski to create the backdrop for the Buenos Aires performance of The Polite Prostitute in 1947. Bernard Shaw also had him design for the Argentine premiere of Androcles and the Lion in 1953. Oski contributed to Landrús magazine Tia Vicenta and much later to Satiricón. When Satiricón was forced to close by executive order in 1974, Oski chose to abandon political subject matter, working instead with Bruto on their unique version of the seminal Salerno School of Medicine’s medieval compendium. The worsening climate of political violence and repression in Argentina during 1975 led Oski to move to Barcelona and later to Rome, where he illustrated a number of Left-leaning periodicals such as the Italian daily newspaper L’Unità. In 1979 he returned to Buenos Aires, where he died on 30 October at 65. Numerous posthumous anthologies of his work have been published since, notably El Maestroski in 1989.

Oski’s Las Boleadores

Hector Oesterheld

Inspiring writer and publisher Hector Oesterheld (1919-1978?) brought a vital humanism and moral consciousness to Argentinian adventure comics. His first major series, the atypical western El Sargento Kirk in Misterix from 1953, followed a cavalry officer who deserts out of disgust at the massacre of an Indian pueblo and sides with the Native Americans. This began Oesterheld’s intense collaborations with Hugo Pratt and several other Italian artists then in Buenos Aires, known as The Venice Group. In 1955 Oesterheld and his brother set up the publishing house Frontera and in 1957 launched two monthly comics, Frontera and Hora Cero (‘Zero Hour’) followed by a Hora Cero weekly supplement. Oesterheld devised the World War II correspondent Ernie Pike, named after the real writer Ernest Pyle, and based by Pratt on Oesterheld’s face. He also revolutionised the classic cowboy in Randall drawn by Arturo del Castillo and speculative sci-fi in El Eternauta drawn by Solano Lopez. The political subtexts in his comics came to the surface in his controversial 1968 biography of Che Guevara with Alberto and Enrique Breccia. In the early 1970s, Oesterheld went underground, scripting revisionist historical works for the left-wing guerilla group Montoneros. On April 27th 1977 he was detained illegally and ‘disappeared’. The truth about his death, presumably in 1978, and that of his four daughters, has never come to light.

El Eternauta by Héctor Oesterheld and Solano López

came to symbolise resistance against oppression.

Solano Lopez

El Eternauta ran from 1957 to 1959 in the weekly Hora Cero semanal as a science fiction adventure serial narrated by an eternal time-traveller. Artist Francisco Solano Lopez (b. 1928) with writer Hector German Oesterheld crafted a chilling vision of Juan Salvo, an ordinary man in the near future, confronting extraordinary terrors in a very real Buenos Aires, decimated by a lethal snowfall and an alien invasion. Salvo becomes part of the resistance, trying to prevent the extraterrestrials from enslaving mankind, as they have already done to other races by implanting a deadly fear gland to suppress all thoughts of revolt. Under the later dictatorships, this saga took on greater meaning and for many its hero became an iconic symbol of opposition to oppression. During the Sixties, Solano Lopez drew for many British boys’ comics on such series as Kelly’s Eye, Galaxus and Janus Stark. He and Oesterheld resumed El Eternauta from 1976 to 1978, but during this time the writer was “disappeared” and Solano’s son Gabriel was arrested and finally freed only on condition that the family leave Argentina. In exile, he remained a prolific artist, returning to his homeland in 1985.

Alberto Breccia

Few comic artists have been as innovative as Alberto Breccia (1919-1993), especially during his last 30 years. Born in Montevideo, Uruguay, Breccia was three when the family moved to Buenos Aires. In his teens, he escaped his father’s and brother’s dead-end job in the abattoir by earning money as cartooning. He joined the staff at Patoruzito in 1945, where he soon switched to a realistic approach influenced by Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff. Teaming with Hector Oesterheld in 1962 on the enigmatic Mort Cinder, Breccia developed a high-contrast chiaroscuro in blocks of solid black and few outlines, increasingly adding expressionism to enhance atmosphere. He constantly experimented, trying monoprints, oil paints on glass, Mattisse-like cut papers and magazine collages. Another Oesterheld project, with Breccia’s son Enrique, was a graphic biography Che Guevara, published in January 1968, barely three months after Che’s death. The military dictatorship were soon seizing copies, compelling Breccia to destroy his original artworks; the book survived because he buried one copy in his garden. After the military gave up power in 1983, Breccia and writer Juan Sasturain unveiled Perramus, a searing, surreal satire of Argentina’s recent history. Audacious to the end, Breccia interpreted Poe, Lovecraft, the Brothers Grimm and José Hernandez’ Martin Fierro, and died leaving twenty acrylics about the work of Borges on his drawing table.

Alberto Breccia: Detail from a cover of the first volume of Perramus, 1983

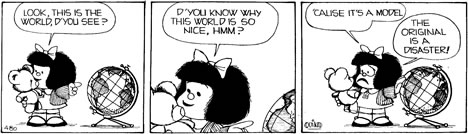

Quino

Joaquín Salvador Lavado, alias Quino (b. 1932), studied at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Mendoza, hoping to work for Rico Tipo magazine. Instead, he broke into Esto Es where his cartooning was soon picked up by other Buenos Aires-based periodicals and North American and European publishers, bringing international success. Quino’s daily newspaper strip Mafalda was his most successful cartooning venture, running from 1964 to 1973 and translated into more than 30 languages. A precocious, outspoken little girl, Mafalda was chosen in 1976 by UNICEF to be a spokesperson for the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The strip, however, never received a wide audience in the English-speaking world, perhaps because, as Quino put it, the strip was ‘too Latin American’. While Mafalda concentrated on children’s views of the world, his later comics featured characteristically cynical humour about ordinary people, often poking fun at real-life situations and using worldess visual comedy to perfection. Among his admirers was Charles Schulz, the creator of Peanuts: ‘The kind of ideas that he works with are some of the most difficult, and I am amazed at their variety and depth. Also, he knows how to draw, and draw in a funny way. I think he is a giant.’

Mafalda by Quino

Roberto (El Negro) Fontanarrosa Rosario

Roberto (El Negro) Fontanarrosa Rosario (1944 - 2007) was both a writer and a cartoonist, who began by writing and drawing comic strips and later short stories, especially about football. He left secondary school in 1961, saying ‘I feel no frustration about dropping out. I am a pioneer of quitting school’. His best-known strips are Inodoro Pereyra, featuring a gaucho and his talking dog Mendieta, and the hitman Boogie el Aceitoso which came to life as a Dirty Harry parody. These both appeared in 1972 in the new humour magazine Hortensia. Later in Fierro, one of his less famous characters Sperman related the adventures of a sperm donor, spoofing Superman and the advances in reproductive science. The jokes in his highly original comics were never simply a punchline at the end, but could arise anywhere within the strip. He loved to make fun of familiar clichés by exaggerating them and placing them out of context. In Satiricon he also published strips based on the stories of Borges and on films and bestselling books. In 1976 his strip Inodoro moved to Clarín, the newspaper with the widest distribution in the country, which made his character massively popular. His books include: Fontanarrisa, (Fontanalughter ) El Rey de la Milonga, (The King of Milonga), Todo Fútbol (All about Football) Argentina para Principiantes (Argentina for Beginners). Several of his works have also been adapted into movies.

An extract from Fontanarrosa’s Inadoro

Enrique Alcatena

Mythologies and histories from around the world are the speciality of Enrique ‘Quique’ Alcatena (b. 1957), often transformed into visionary tales of the fantastic. Although he had no formal art education, Alcatena learnt on the job when he was hired at the age of 18 by the publisher Ediciones Record. He began as an assistant to Chiche Medrano and drew for the adventure anthology Skorpio launched in 1974. He branched out on his own from 1979 by working for Scottish publishers D.C. Thomson. Granted considerable creative freedom, he found his own voice here while illustrating forty-six science fiction and fantasy stories for the Starblazer pocket libraries. On his return to Skorpio in 1987, he unleashed his first heroic fantasy epic, The Mobile Fortress, written by Ricardo Barreiro. A long-term partnership with the Argentinian writer Eduardo Mazzitelli produced Gods and Demons, in which they develop cycles of tales dealing with myths of their own invention. Having grown up on American superheroes, Alcatena was able to draw episodes of Batman, X-Men, Green Lantern, among others. He is also writing his own stories, notably The Secret Book of Marco Polo, fabricating the explorer’s encounters with imaginary creatures. His eclectic artistic and literary inspirations infuse his pages with exceptional imaginative richness.

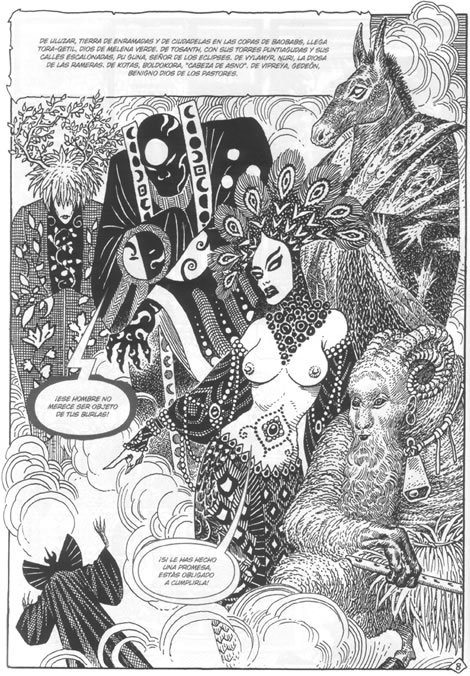

Original art from Dioses y Demones (‘Gods and Demons’)

drawn by Enrique Alcatena and written by Eduardo Mazzitelli

Oscar Grillo

From the moment he saw Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs at the age of five, Oscar Grillo (b. 1943 ) knew he wanted to be an artist. When he reached the age of 16, spotting an advert for trainee animators, he found himself working on his first animated commercial. Leaving Argentina for a European working trip, Grillo eventually arrived in England in 1971 on a two-week storyboarding stint at Halas & Batchelor and his career has been based here ever since. By 1980, he had worked for seven years for Dragon Productions and his animated song video Seaside Woman, based on the reggae number written and sung by Linda McCartney and released by WIngs, won the Palme d’Or Award for best short subject at Cannes. In 1981 he and Ted Rockley set up their own animation company, Klactoveesedstene, named after a Charlie Parker tune, and produced many memorable animated adverts from Kia-Ora to Cheetos. Among his comics are the 1983 surreal fairytale The World Is Round written by Graham Marks and his 2009 graphic novel adaptation of the complete text of Shakespeare’s play The Tempest from Can of Worms Publishing. Grillo’s passion for pure drawing bursts forth from everything he illustrates.

Grillo: La Petite Illusion, a homage to Segar’s Popeye

José Muñoz

After studying at the Escuela Panamericana de Arte under Pratt and Breccia, the artist José Muñoz (b. 1942) worked as an assistant to Solano Lopez. The writer Carlos Sampayo (b. 1943) first earned a living from his reviews of literature and music, especially jazz, and the advertising industry. Through their mutual friend Oscar Zarate, the two were introduced in Buenos Aires in 1971, but they would not meet again until 1974, after they had both left Argentina, Muñoz moving to London and Sampayo to Spain. The rapport was instant and their extraordinarily close and fertile collaboration brought international acclaim. A year later, Alack Sinner, a principled ex-cop-turned-detective, debuted in France and Italy. Muñoz and Sampayo captured the gritty intensity of New York, though they had never visited the city at the time. They soon broke away from the classic crime genre to address Sinner’s personal troubles and social and political issues, from Viet Nam to Nicaragua. Among their other co-creations are the poignant vignettes of lost souls in Joe’s Bar, short tales about Latin America in Sudor Sudaca, and graphic biographies of jazz singer-songwriter Billie Holliday and tango legend Carlos Gardel. Muñoz has worked with other authors, including American novelist Jerome Charyn, and won the 2007 Grand Prix at the Angoulême International Comics Festival.

Jose Muñoz: Detail of an illustration from Alack Sinner.

Horacio Altuna

Born in Cordoba, Horacio Altuna (b. 1941) started working for in comics in 1965 and from 1967 illustrated for Editorial Colomba, co-creating Kabul de Bengala with scripts by Oesterheld, and other characters. Refining his draugtsmanship, he achieved a delicate balance between naturalistic realism and understated comedy. From 1973 to 1976, he worked for both Argentinian and foreign publishers, including British action comics for Fleetway. From 1975 to 1987, with writer Carlos Trillo, he produced the daily strip El loco Chavez in the paper El Clarín. The racy maverick reporter became so popular, thay he was adapted into a television series, which was abruptly cancelled by the military censors. Another remarkable series with Trillo was Las puertitas del señor Lopez. Whenever life becomes too much for Lopez, the short, chubby, balding clerk can escape through a bathroom door into worlds of his imagination, though inevitably he has to return to reality. Readers recognised in these failed fantasies an existential resonance with their lives and dreams under the dictatorship. The situation eventually led to Altuna leaving Argentina in 1982 for Sitges, Spain, where he continues to paint adventure and erotic comics in full colour for the European magazine and album markets.

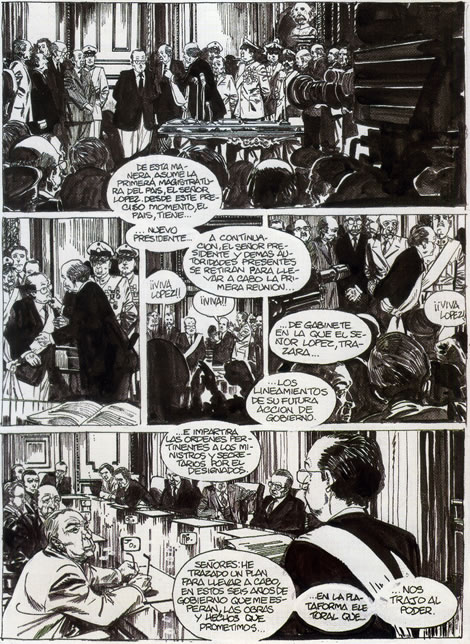

Las puertitas del señor Lopez

written by Carlos Trillo and drawn by Horacio Altuna, 1980.

Oscar Zarate

As a boy, Oscar Zarate (b. 1942) idolised Breccia, Pratt and his other heroes of 1950s comics. In his teens, Zarate found a job at Ediciones Frontera outlining their balloons and captions, but instead studied architecture and made advertising his career. Disenchanted with the moral compromises of his success, he returned to his first love, comics, leaving Buenos Aires in 1971 to start afresh in London. Here he drew educational comics such as Introducing Freud, which sold 180,000 copies in 24 languages, as well as adapting Shakespeare’s Othello and Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus. Zarate developed the original graphic novels Geoffrey the Tube Train and the Fat Comedian with Alexei Sayle and A Small Killing with Alan Moore, which won the 1994 Eisner Award for best graphic novel. In 1996, he edited It’s Dark in London, a collection of noir graphic short stories. Since 2006 he has been collaborating with Carlos Sampayo for French-language publishers, producing Trois Artistes à Paris for Dupuis, and Fly Blues, serialised in Argentina in Fierro magazine, and La Faille for Futuropolis. Pais Abollado, his latest short story for the bicentennial anthology La Patria Dibujada, confronts Argentina’s 2001 financial crisis.

First page of Pais Abollado written by Lautaro Ortiz

and drawn by Oscar Zarate for La Patria Dibujada, 2010

Eduardo Risso

His blend of the grotesque and sensuous, his striking angle shots and layouts, and mastery of line and shadow, have made Eduardo Risso (b. 1959) an international phenomenon fêted in America and Europe as well his homeland. He began by drawing humorous cartoons for the newspaper la Nacion and illustrating for the Columba magazines Satiricon and Eroticon. His initial collaborators were the Argentinian scriptwriters Ricardo Barreiro and Carlos Trillo. In 1987, Barreiro wrote the series Parque Chas for Fierro magazine, followed by Fulù in Puertitas by Trillo. Thus began the prolific Risso-Trillo partnership on such projects as Video Nocturno, Boy Vampiro and Borderline initially for the French market. Chicanos in 1997 portrays a short, plain Hispanic woman, a sort of noir ‘Ugly Betty’, surviving as an unlikely New York private eye. Risso was headhunted by American publishers, starting in 1997 on the comics adaptation of the Aliens Resurrection movie. His big breakthough came in 1999 working with writer Brian Azzarello on the DC Vertigo 100-issue crime saga 100 Bullets for which he has won four Eisner Awards. More recently, Risso has illustrated Batman and Wolverine, and a full-colour story Muerte Blanca for the bicentennial anthology La Patria Dibujada.

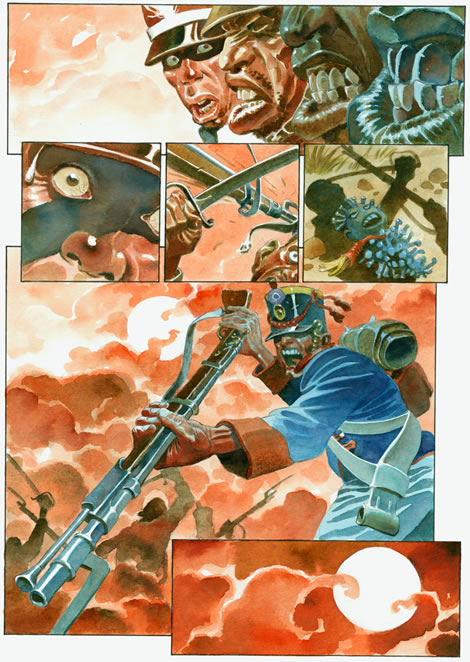

Page from Muerte Blanca written by Diego Agrimbau

and drawn by Eduardo Risso for La Patria Dibujada, 2010

Ricardo Liniers Siri

From a tender age, Ricardo Liniers Siri (b. 1973) loved to draw. He studied advertising, but switched to cartooning, adopting his middle name as his nom de plume in tribute to an ancestor, a viceroy executed by firing squad. Although Liniers’ submissions were rejected at first for making no sense, in 1999 he landed a weekly strip Bonjour in the supplement NO! in the Pagina / 12 newspaper. In 2002, cartoonist Maitena Burundarena introduced Liniers to the important Argentinian daily paper La Nación, where he began the daily strip Macanudo. Its success took his absurdist humour and surreal characters across South America and to Europe. A fountain of cartoon creativity, Liniers has exhibited his paintings, illustrated travel journals, including a trip to Antarctica translated in Virginia Quarterly Review, and toured with singer-songwriter Kevin Johansen, drawing live to his songs and visiting Britain in 2010. Married with two daughters, he and his wife have set up their own company, Editorial Común, to publish his Macanudo collections and other graphic novels. Among his admirers, the cartoonist Fontanarrosa warned: ‘Liniers style is naive. But beware, unsuspecting passer-by! The greatest trick of the lion is to be able to morph into a gazelle.’

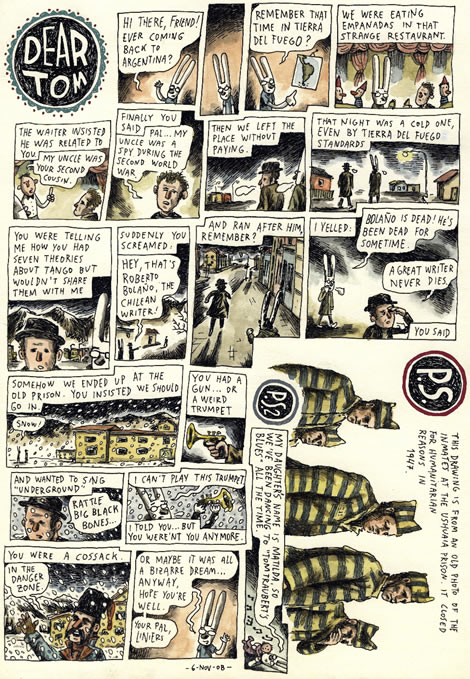

Liniers strip from Loops 1, a British journal

on new music writing from Faber, 2009

Alejandra Lunik

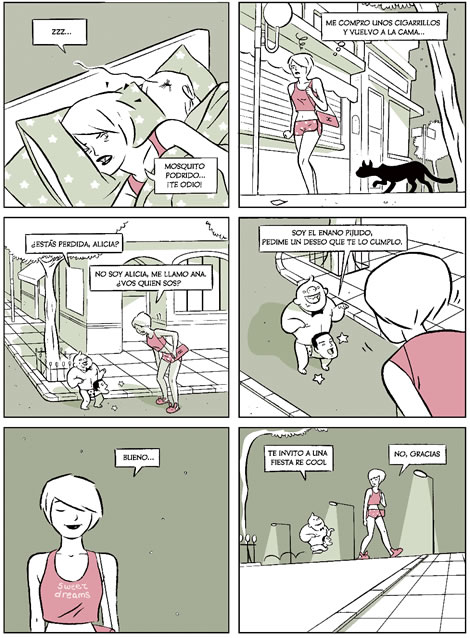

Until quite recently, women creators have usually been underrepresented in comics. When one female cartoonist was asked why, she suggested, ‘Perhaps they have more common sense.’ In Argentina, Maitena Burundarena (b. 1962) became one the field’s first high-profile women, drawing sexually charged comics for Fierro and satirical strips for the national press. The revived Fierro promotes fresh female voices, notably the Chilean-born Alejandra Lunik (b. 1973). Co-written with writer Laura Vazquez, Historia de Ana, el mosquito y un enano (‘Story of Ana, the Mosquito and the Dwarf’) is a magic-realist drama charting a thirty-something woman’s professional and emotional crisis and a strange dwarf who visits her only at night. Lunik both wrote and drew Mira que no somos novios, a series of monologues spoken by different women recounting how life affects them and refecting the author’s own family and social circle. Lunik also works as an illustrator in the new pop-surrealism wave and has created charming full-colour children’s comics starring Ninochan y Chanchilas.

Opening page from Historia de Ana, el mosquito y un enano

drawn by Alejandra Lunik and written by Laura Vazquez

Jorge Gonzalez

Born and raised in Argentina, Jorge Gonzalez (b. 1970) left for Spain where he has been living for the last fifteen years. Linking up with fellow Argentine comics creator in Spain, Horacio Altuna, Gonzalez illustrated his scripts, starting with Hard Story for Spanish publisher Norma, followed in 2005 by Hate Jazz for Glénat, Belgium. Gonzalez has created several other graphic novels for Spain and France, newspaper strips for El Pais, advertising illustrations, storyboards and a short animated film, Jazz Song. In 2008, he won the FNAC Spain Graphic Novel Award for his revelatory evocation of his homeland, bathed in luscious sepia tones, entitled Fueye. Nostalgic for a noisy, colourful Buenos AIres from the past which he never knew, Gonzalez plunges us into the life of Horacio, a child prodigy on the piano, who is entranced by the passion of the tango musicians. Growing up into a talented young man, Horacio will stop at nothing to become their equal, even if he has to break promises or compromise his principles. Gonzalez contrasts this in the second part with an impressionstic travelogue of his brief return visit to family and friends in Argentina, reflecting on his own feelings about his Argentinian roots, his passion for tango, his creativity and identity.

Jorge Gonzalez: Detail from the cover of Fueye (2008).

Pablo Holmberg (Kioskerman)

Today’s up-and-coming comics artists can hone their skills and build their audience entirely online and many are debuting via the growing arena of webcomics. Among these webtoonists is Kioskerman, a playful pen-name of Pablo Holmberg (b. 1979). He started publishing his comics on the internet in 2004 and chose the daily strip format to try with two types of stories: one combining humour and the absurd, entitled Señor del Kiosco between 2004 and 2006, the other as a space for experimentation and creating worlds, entitled Eden, between 2006 and 2009. Kioskerman plays with pens, paper and print as much as with palettes and pixels. He has self-published the fanzine Flasia with his friends in 2005 and a diary in a colour tabloid format, El libro-diario del Señor del Kiosco, in 2006. In 2010, Eden is being published in Canada, in English by Drawn & Quarterly and in French by La Pasteque. His work’s lightness of touch and philosophical tone distinguish Kioskerman as one of Argentina’s true 21st century originals.

Front cover of the Eden book collection

Juan Sáenz Valiente

A rising star of 21st century Argentinian comics, Juan Sáenz Valiente (b. 1981) demonstrates a versatility and subtlety well beyond his years. The son of well-known animator Rodolfo Sáenz Valiente, he assisted his father on the instructional book Arte y técnica de la animación and produced his own short animated film Jubilados in 2003. His breakthrough graphic novel was the noir drama Sarna written by Carlos Trillo in 2004 and translated into French in 2005. Episodes of his next major work ran in the revived Fierro magazine from 2007, where he collaborated with acclaimed novelist Pablo De Santis. El Hipnotizador is the ingenious story of a troubled theatrical hypnotist, who moves into a run-down Buenos Aires hotel hoping finally to be able to sleep. As he applies his mesmerising skills to assorted bizarre cases, he gradually resolves the issues behind his insomnia. This too was published in France by Casterman. Also in 2010, Valiente released Matufia compiling 15 short stories in black and white, all but one written by him, proving his breadth of styles and subjects. A keen skateboarder, he also played a cartoonist in the 2009 TV series Impreso en Argentina, who with historian Diego Valenzuela investigates the country’s 19th-century history and literature.

Detail from first page of El Hipnotizador