Best Crime Comics:

Every Shade Of Noir

The following article originally appeared as the introduction to the comics-anthology The Mammoth Book Of Best Crime Comics, edited by Paul Gravett and designed by Peter Stanbury, published in July 2008. Best Crime Comics is a 480-page collection of 24 of the greatest crime comics ever - some of the slickest, moodiest graphic short stories ever collected, from the mean streets and sin cities of crime. They range from America’s classic newspaper-strip serials and notorious uncensored comic books to modern graphic novel masterpieces and features some of the greatest writers and artists in comics, including Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Joe Simon, Jack Kirby, Johnny Craig, Alex Toth, Bernie Krigstein, Jack Cole, Jacques Tardi, Gianni De Luca, Paul Grist, Charles Burns, Will Eisner, Alex Raymond and others.

If your only real exposure so far to crime comics has been the Sin City graphic novels by Frank Miller or maybe their faithful big-screen adaptations, you’d better fasten your seat belt, you’re in for a foot-to-the-floor ride through this compendium of the cream of crime comics. Along the way, you’ll see how several of Miller’s acknowledged masters and peers enthrall with their pacing, atmosphere and verbal and visual panache. You’ll also see how Miller’s battered, bandaged Marvin belongs in a long line-up of lean, mean machismo going back to the Thirties and before, when gangsters fought the cops for control of America’s cities.

It was a war back then, fought on the streets and in the strips. Newspaper comics may have started out as ‘The Funnies’ offering mainly light relief from the grim front pages, but all that changed on August 13th 1931. After ten years of rejections, cartoonist Chester Gould received the telegram he’d been waiting for: publisher Captain Joseph Patterson of the Chicago Tribune syndicate wanted to see him about his latest ideas for a strip, Plainclothes Tracy: "I decided that if that police couldn’t catch the gangsters, I’d create a fellow who could." Gould kept that telegram framed on the wall as his most cherished possession, after Patterson signed up Gould’s concept, shrewdly shortening the name to the punchier Dick Tracy, who rapidly became a circulation-boosting phenomenon.

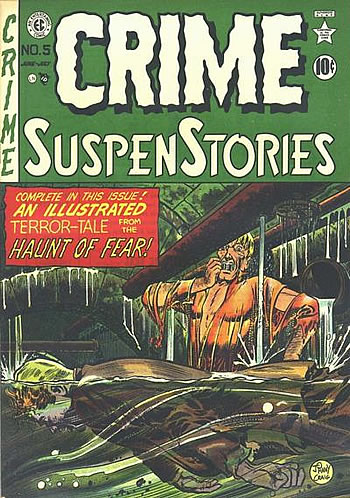

Crime SuspenStories #5, 1951

featuring The Sewer, script and art by Johnny Craig

cover art by Johnny Craig

Rival press baron William Randolph Hearst at King Features struck back in 1933 in his typical fashion, paying whatever it cost to buy the very best. For $500 a week, Hearst secured the hugely popular author Dashiell Hammett, in need of ready cash to finance his spendthrift lifestyle. Once more, Hammett, an ex-field operative for San Francisco’s Pinkerton Detective Agency, remixed his genuine experiences to devise a fresh hero for the newspaper strips. In trench-coat and snap-brim, the keen-witted, determined mystery man Secret Agent X-9 was assigned to Alex Raymond. This rising young illustrator was set to launch Flash Gordon and Jungle Jim in colour Sunday pages on January 7th 1934. The very next day, what was to be Hammett’s last novel, The Thin Man, hit the bookstores.

Building on all this publicity, X-9 burst into the daily papers on January 22nd. That day, Hammett wrote to his wife, "I’m writing a story for a cartoon strip for Hearst’s syndicate which will bring me a regular and, I hope, growing income perhaps forever." It was not to last, however; once he fell behind with scripts, King Features meddled with them and Hollywood beckoned. Even so, in its prime, and in the climactic twenty weeks of his first long serial resurrected here, X-9 ranks, according to his biographer William F. Nolan, as "...Hammett at his pulpy best. The author’s never-equalled mastery of understatement and his dead-pan but deliberate use of self-parody are in abundance here and seem to indicate that Hammett was having a ball." It marked Hammett’s last words printed in his lifetime; from now on, his writing would be for the movies.

It wasn’t long before X-9, Tracy and other detective strips were repackaged in comic books, the emerging 10-cent novelties that turned into a multi-million dollar industry with the success of Superman, Batman and the rest. Before them, however, their New York publishers had set up a company called Detective Comics, Inc. in 1936 to publish one of the first single-theme anthologies, Detective Comics. This was not only the birthplace of The Dark Knight and his home to this day, but also the source of DC Comics’ initials. During the Second World War, while superheroes, essentially costumed crimefighters, dominated comic books, the crime genre developed elsewhere in America, for example in Will Eisner’s newspaper supplement The Spirit, a veritable weekly primer on how to expand the audience and expressive power of the medium.

True Crime Comics#2, 1947

featuring Murder, Morphine & Me by Jack Cole

cover art by Jack Cole

Publisher Leverett Gleason also recognised that the readership was changing and ageing, so in 1942 he took a gamble on a novel approach from cartoonist-editors Charles Biro and Bob Wood. They took the sort of real-life, supposedly "true" prose accounts of murderers and criminals which had sold pulp magazines in the Twenties and were a staple of the tabloid press and on the big screen, and reinterpreted them as comics, where every lurid detail could be visualised and fixed on the page. The first, and for several years, the only "All True" crime comic book in America, Crime Does Not Pay slowly but steadily sold more each year. As demobbed troops increased the adult audience, by 1948 it topped one million copies per month. Multiply that by the "pass-along" rate and Gleason could justify the cover line, "More Than 6,000,000 readers monthly!" No wonder that year triggered a sudden two-year crime wave in comic books. Gleason’s competitors would range from the delectable sleaze of Fox’s Crimes By Women or Magazine Village’s True Crime to the classier acts of EC or Simon and Kirby, all represented here.

Crimes By Women #5, 1949

featuring Mary Sprachet by anonymous

Although the genre never reached such a peak, overtaken from 1950 by booms in romance and horror, it was these unrestrained crime comics that first stirred up a moral panic about their power to corrupt young minds and turn them into juvenile delinquents. Vilified in the media, the target of local bans and boycotts, subjected to televised Congressional hearings, comic books became a burning issue of the day, literally as parents, teachers and reluctant, pressurised kids threw piles of them onto public bonfires. To avert legislation, most of the big players in the industry ganged up in 1954 to appoint an independent Comics Code Authority to apply the strictest self-imposed code of content on any medium. Twelve clauses cleaned up crime comics overnight by outlawing, among other things, "excessive violence", "kidnapping", "unique details and methods of a crime" and "disrespect for authority" and insisting that "in every instance good shall triumph over evil." It was no better in the newspapers at this time, when complaints about a scene of bondage in Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer strip forced its cancellation.

Constraints like these meant that crime definitely did not pay for America’s comic book publishers and the genre all but vanished by 1959 as superheroes took over once more. Readers looked for their crime thrills in books, films and television cop shows, which from the early Sixties were spun off into comic books. In that era before videos, DVDs and countless channels running repeats, comics like these allowed viewers to enjoy new episodes of their favourite shows anytime, anywhere. The majority were put out by wholesome company Dell and were pretty tame, but at least one of their uncredited writers was a total maverick, as proven by his 87th Precinct story based on the TV series and Ed McBain’s novels.

Crime Does Not Pay #64, 1948

featuring Who Dunnit? by Fred Guardineer

cover art by Charles Biro

Apart from brave one-off experiments like Gil Kane’s Savage, Jack Kirby’s In the Days of the Mob or Jim Steranko’s Chandler, darker, more mature crime comics struggled in America, but they would flourish elsewhere. From fumetti neri or pocket-sized black comics in Italy to the French revolution in quality bande dessinée magazines and albums, it was European-based creators starting the Seventies, like Jacques Tardi, Abuli and Bernet, Gonano and De Luca, and Muñoz and Sampayo, who were largely free from censorship to explore the many shades of noir in truly sophisticated narratives for adults.

Meanwhile, back in Code-approved America, nobody was publishing crime when a fledgling Frank Miller broke into comics. The only game in town was superheroes. So in 1979 when he landed the pencilling and then writing jobs on a languishing Marvel B-feature Daredevil, Miller stripped it back to its essence of a lone blind man fighting for justice as a lawyer and costumed vigilante. It was as close as he could get to the crime comic he had always dreamt of producing.

Crime & Punishment #31, 1950

featuring The Button by Bill Everett

cover art by Charles Biro

There were always limits when working under the Comics Code, still restricting newsstand comics. But the Code became irrelevant when another market emerged through specialist comic shops, allowing publishers big and small to sell directly to fans. Out of this explosion, Max Allan Collins and Terry Beatty paved the way in 1981 with avenging widow Ms. Tree, as brutal as Hammer but a good deal smarter. Ten years later, Miller took the plunge and created his own personal universe to play in, Sin City. Thanks to the graphic novel positioning comics into bookstores, libraries and the best-sellers lists, the diversity and quality of today’s crime comics, in America and worldwide, are unprecedented. Once more, acclaimed crime novelists such as Greg Rucka, Jerome Charyn and Ian Rankin are taking up the challenges of scripting comics. At last crime really can pay, and not just the publishers but the writers and artists as well.

It’s a different world from those heydays of classic newspaper strips and comics. Their often stratospheric print runs might lead you to assume that there’s a plentiful supply still in existence. The fact is, millions of pages of fading newsprint have been disposed of, thrown onto those anti-comics campaigners’ pyres, recycled in war-time paper drives, sent far afield as ships’ ballast, dumped even from overloaded libraries in the rush to microfilm or digitise. To the point where today surviving original copies are few, fragile and highly prized and priced. Rarer still are the unique original artworks. So I want to thank Martin Barker, Max Allan Collins, George Hagenauer, Denis Kitchen, Frank Motler, Ian Rakoff, Roger Sabin, Greg Sadowski and all the other connoisseurs who helped me to rescue and research these treasures for this compilation and most of all Peter Stanbury for dedicating such care and skill to their restoration and presentation. And, of course, my gratitude goes to the writers and artists for their brilliant work. Comics are both a vital part of our cultural heritage and the sharpest cutting edge of twenty-first century literature. This is one story that is definitely "to be continued…"

Posted: August 24, 2008