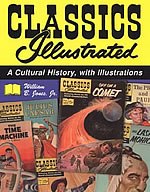

Classics Illustrated:

A Cultural History

"Good stories". That was the way the author’s father explained to him what Classics Illustrated meant. William B. Jones, Jr. was only five at the time and begged his Dad to buy him a 1955 issue he had spotted on the drugstore spinner with his television favorite Davy Crockett on the cover. By the age of six, young Billy was a serious Classics collector. His ninth birthday treat was a trip to the Aladdin’s cave of a local distributor’s warehouse piled high with copies, to pick out as many missing numbers as he wanted.

These were the beginnings of Jones’ lifelong passion, both for these comics and for the literature which they stimulated him to explore as a young adult. Like many others, he followed the instructions that concluded most issues: "Now that you have read the Classics Illustrated edition, don’t miss the [added] enjoyment of the original, obtainable at your school or public library." A father himself now, Jones has pooled years of research, interviews and correspondence, by him and by Hames Ware, Jim Vadeboncoeur, Dan Malan and other experts, into this thorough 280-page survey of one of the 20th century’s most successful enterprises in mass education publishing.

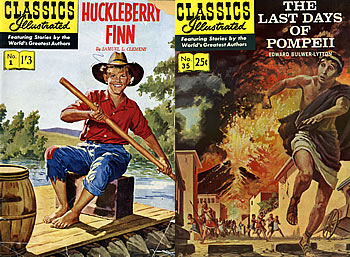

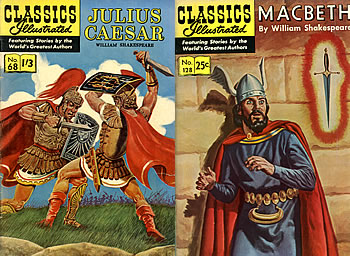

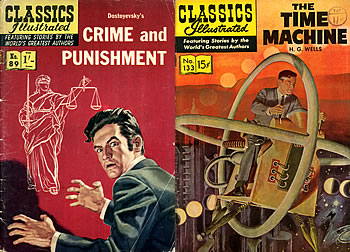

From the racks, the Classics Illustrated logo at the top left of every cover grabbed the eye like a beacon. The figures prove that the power of the yellow rectangle should not be underestimated. Jones estimates that of the 169 different stories adapted in America from 1941 to 1971, there were 1,343 printings, usually of 100,000 to 250,000 copies each. There were a further 432 printings between 1953 and 1971 of the 77 Junior fairy tale editions. Then there were the international translations into 26 languages in 36 countries, as well as new adaptations in Brazil, Greece and Britain. The illustrators were paid just a flat, once-only fee and most of the authors were long dead, so no reprint fees or royalties were due. With peak monthly sales in the USA of two to four million copies, it was virtually a license to print money.

Jones charts the fortunes of Russian Jewish immigrant Albert Kantner (1897-1973), who in 1941 conceived of Classic Comics as self-contained abridgments of a literary work into a single comic book. To produce the first issue, The Three Musketeers, Kantner and his partners gambled $8,000 for 250,000 copies; they tripled their investment. From these modest beginnings, Kantner built his family’s lucrative Gilberton publishing empire. His brother Michael was warehouse manager, and his two sons played important roles. William was an editor (1946-56), later moving to England to supervise a European programme of new titles, while Hal, working inside Hollywood, could set up tie-ins with forthcoming movies.

Gilberton’s decline and fall were triggered in 1961 by the loss of its second-class mailing permit, vital for the company’s subscription and mail order services. Jones identifies other factors: vanishing outlets, as local stores were replaced by supermarkets; cheap paperback editions of classics aimed at kids; the decision by the F.W. Woolworth chain, one of Gilberton’s main retailers, to stop stocking comic books due to declining sales; and the inexorable, seductive power of television. Gilberton’s U.S. operation was forced to stop all but a handful of new titles and stick to reprints and revivals of retired issues. Finally, Kantner decided to sell off Classics Illustrated in December 1967 for half a million dollars to entrepreneur Patrick Frawley, whose efforts sadly failed to save the company from closure on April 21st 1971, nearly thirty years after Kantner’s dream had begun. Jones examines subsequent attempts to continue Classics Illustrated, by First Publishing in 1990-91 and Acclaim in 1996-98, both short-lived.

Through thirty six chapters, twelve appendices and an eight-page colour gallery, Jones offers perceptive criticism of every issue and artist, considering their strengths and failings. His longer profiles of significant colorful Classics illustrators bring them to life. There’s the panache, on and off the page, of the feisty, red-haired Louis Zansky, later an award-winning painter, who had his cheque bounce and threatened to throw Gilberton’s business manager out of the window unless he paid him there and then in cash. Two illustrators of the old school, the tall, flamboyant, Paris-trained H.C. Kiefer, sporting a cape and aristocratic airs, and Hungarian-born etcher Alex Blum, always impeccable in suit and tie, gave the comics a resonant, anachronistic antiqueness. Their successor was the equally gentlemanly Norman Nodel, who brought his experience of singing and acting in the St. Louis Opera Chorus, notably in his depiction of Faust.

Younger blood came from former movie-poster artist Rudy Palais, famed for his ‘cinematic’ angles and prolific use of ‘plewds’ or sweat drops, and from the hearty Lou Cameron, the ‘John Wayne of comic books’. On The Count Of Monte Cristo, Cameron was ready to quit over Gilberton’s editorial meddlings and insensitive management, so he rewrote some speech balloons, one of which said "I condemn you also to die of boredom, as this is almost the end of the story". The editors spotted and corrected them in time and never commissioned Cameron again, but he’d enjoyed a little revenge. The most demanding editor was Roberta Strauss, a stickler for detail, who would count soldiers’ buttons or pleats in skirts and even called an editorial meeting in her hospital room only days after her son’s birth. First-hand anecdotes such as these add humor and humanity to Jones’s study.

In all, dozens of artists and some scriptwriters are credited and analyzed here, although some credits still baffle the experts, including those of several handsomely painted covers, and of the interior art to the second 1961 versions of Adventures Of Cellini and The Adventures Of Tom Sawyer. To me, the crisp elegance and refined composition of the Cellini artwork strongly suggest it was drawn by Dino Battaglia (1923-83). After all, who better to adapt the Italian Benvenuto Cellini’s autobiography than an Italian comics maestro? By 1961, he had already been working for some years for publishers in Britain, where he might have come to William Kantner’s notice. I’d love to hear what others think.

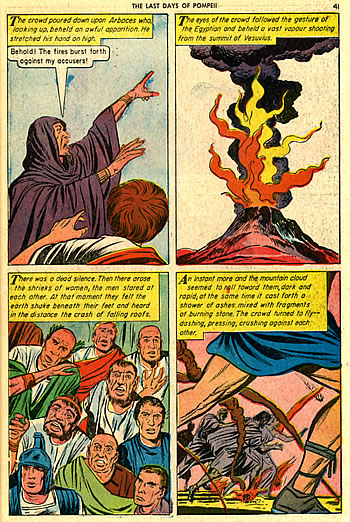

Classics Illustrated lived up to Kantner’s noble goal of introducing famous tales to a new readership, but for a fair share of lesser stories it was their last outing before becoming all but forgotten. Geoffrey O’Brien put it well in The Village Voice Literary Supplement, January/February 1989: "The titles adapted were books in the library of someone’s parents, a fixed body of tradition to be handed on. But the ground was already shifting. Many of the ostensibly deathless works were in fact dying. How many would ever again seek out Lorna Doone or Under Twin Flags or The Scottish Chiefs? Rather than celebrating the renewal of tradition from generation to generation, the Classics became testimony to a tradition’s gradual erasure, a four-colour funeral pyre."

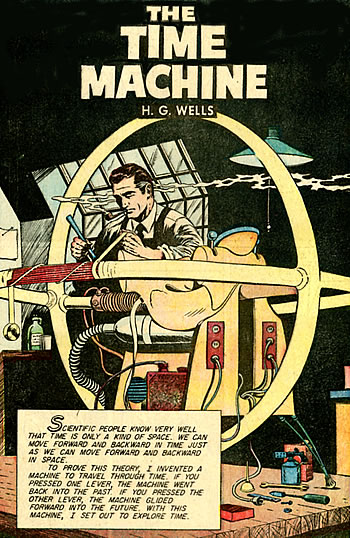

Nevertheless, the Classics line did perpetuate many literary masterpieces which look set to never disappear thanks to fresh interpretations for future generations. Hollywood has made recent blockbuster versions of The Time Machine and The Count Of Monte Cristo, television revivals of Dickens or the Bronte sisters continue to sell to channels worldwide, and comics creators are still adapting the classics, from Lorenzo Mattotti’s Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde for NBM Books to P. Craig Russell’s The Ring and other opera for Dark Horse. Lou Cameron was right when he said, "It began as one of the best ideas in the field." It still is, because after food, clothing, shelter and companionship, our other primal need will always be for more "good stories" like these.

The original version of this article appeared in 2003 in the pages of Comic Book Marketplace.