Charles Burns:

Black Hole

In 1955, pressure from parents, teachers and an unlikely alliance of the Church and the British Communist Party resulted in a united House of Commons approving a “Harmful Publications” Act to crack down on the excesses of cheaply reprinted American horror comics. None of those politicians and moral guardians could have dreamed that 50 years later horror comics would be published as lengthy graphic novels for adults in handsome hardbacks by British literary publishers.

Black Hole harks back to those notorious forebears, but its terrors are far more insidious and unsettling than the short, sharp, tongue-in-cheek shockers of Tales From The Crypt. The terrors in Black Hole are those of losing control over our own bodies, of puberty’s raging hormones and “the bug”, a mysterious, sexually transmitted pandemic that is mutating a group of American high-school students, with the result that one acquires a tail, another grows lion-like facial hair and another sheds skin like a snake. All perceive themselves as freaks.

Charles Burns has said that the book’s characters and events are directly based on his life growing up in suburban Seattle, Washington during the 1970s: “Not that my friends had strange growths coming out of their necks, but I really did feel like I was some kind of diseased teen.”

While parallels with Aids are obvious, this is no simplistic cautionary tale. Burns is not interested in explaining the plague’s origins or meanings, nor the search for its cure.

He prefers to explore how it changes these young people’s identities and their relationships with each other and the so-called normal world. He takes time here to unravel the anxieties and alienation familiar to many of being a teenager, apathetic and adrift.

Rather than the disposable cipher victims of schlocky B-movies, these are vulnerable, sympathetic misfits at the mercy of peer pressure and their sex drives. Drugs and drink offer them only a temporary escape. All they really long for is to get away from the sterility of home and school and to connect emotionally with others.

Much of the horror is kept out of view or understated, working on the reader’s imagination and making the revelatory moments all the more disturbing. In one close encounter, while first making love to her boyfriend Rob, the uninfected Chris discovers something while kissing his neck, a tiny second mouth just below his T-shirt. Everything falls apart after Rob has infected Chris. They feel ostracised from their classmates and families, yet increasingly close to each other. Shunned by society, they join the other mutated kids hiding out in the woods in a fragile supportive community.

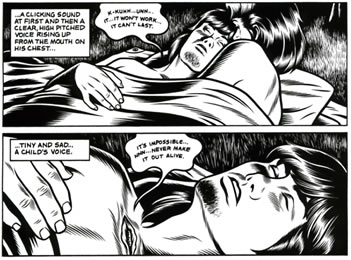

In one scene, the doomed lovers skip school and drive out to the coast for a night of sex under the stars. As Rob falls asleep, the mouth on his chest begins to speak sadly, a tiny voice lost in the enormity of nature, whispering “It won’t work…”

Rob’s orifice is one of a number of the book’s vaginal symbols that represent the pleasure and pain of burgeoning sexuality. Dissecting a frog in science class, removing a shard of glass from Chris’s foot, splitting her skin along her spine when she too starts to shed are among the dark, bodily openings, the “black holes” that pervade this drama.

Despite the dangers, another couple, Keith and Eliza, finally cannot resist sleeping together. Eliza’s mutation is a seductive tail with a life of its own, even after Keith, in his excitement, snaps it off. Burns fills the wild outdoors with other phallic symbols such as branches, snakes and broken bones.

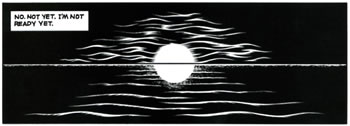

Adopting a trance-like slowness, he reveals the crossed paths of his tragic players, who speak through acutely observed internal monologues and provide perspectives on the same events from differing viewpoints. He adds rippled edges to his panels, akin to the watery dissolves of flashbacks in vintage films, but he also uses them to move the reader in and out of nightmares, drug-induced trips or aspirations for the future, deliberately blurring the boundaries between memory and fantasy.

Described by Robert Crumb as “almost inhuman”, Burns’s monochrome artwork recalls the hard-edged precision of mass-produced comic books, the sort sampled by Roy Lichtenstein. There is no room for greys or tones in his drawings; his is a world seen in black and white, more black than white. His deep shadows and textures on bodies, hair, clothes and vegetation shimmer inside his brushstroke outlines, as jagged as a chainsaw.

The book closes on another recurring image, a setting moon across water, a sort of “black hole” in reverse that keeps beckoning to Chris until the end. Called back finally to the sea, she remembers how another infected, lonely pupil used to look before and how she used to despise “geeks” like him. Now she is on the receiving end of rejection herself, but there is no going back to her “boring, normal life” again. Black Hole exposes in psychological and biological intimacy the cost of the desperate desire for acceptance.

The original version of this article appeared on 21 September 2005 in The Daily Telegraph.