Art Spiegelman:

MetaMaus

How wrong Vladek Spiegelman would turn out to be, when he first warned Art, his enquiring son, that “People don’t want to know about such stories”. Maus, Art Spiegelman’s interpretation into anthropomorphic comics of his father’s tape-recorded oral history of surviving the Holocaust, would become a Pulitzer prize-winning best-seller and a phenomenon that forever transformed perceptions of the graphic novel as a valid vehicle for memoir, biography and autobiography. The task which Art had naively envisaged taking him two years would consume thirteen, and to this day the struggle, success and legacy of Maus cast a long shadow over him.

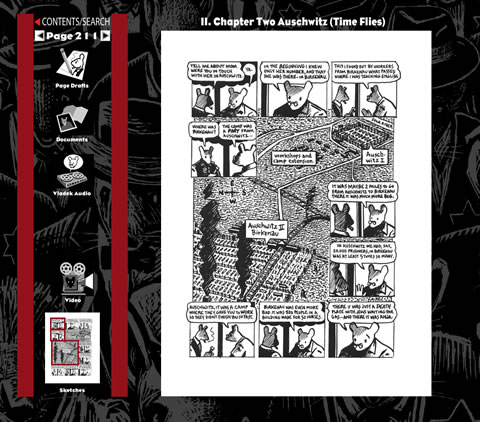

Twenty-five years after its first publication in book form, Art has compiled MetaMaus, the print equivalent of a movie’s most copious DVD extras, encompassing scripts, first drafts, deleted scenes, a ‘director’s commentary’, making-of and more behind-the-scenes materials. In fact, this 300-page hardback, as long as Maus itself, comes with its own hyperlinked DVD of voluminous “supplementary supplements”.

MetaMaus DVD Screenshot

The field of ‘Maus-ology’ studies is already considerable; apart from Hergé‘s finite Tintin albums, there may be no specific corpus in the medium other than the two volumes of Maus which has been so intensely investigated. Nevertheless, Art felt a need to reply definitively to three persistent questions: “Why the Holocaust?”, “Why Mice?”, and “Why Comics?”

Just as Maus was constructed around Art’s interviews with his father Vladek starting in 1972, so MetaMaus‘s structure comes from three thematic in-depth interviews with Art, perceptively conducted by Hilary Chute. These are illuminated with carefully chosen and positioned extracts, sketches, photos, original artwork, as well as further short comics, several from The New Yorker, and other illustrations and prints produced post-Maus.

In many ways, while resolving never to produce a Maus III sequel, Art has never entirely finished with Maus. Ever since, while he does draw himself at times with a human cartoon head, he still often represents himself wearing that minimalist mouse mask, playing his other meta-self as a child of a survivor, and as a survivor himself. On MetaMaus‘s cover, Art’s single mouse eye, its pupil a swastika with a feline Hitler at its centre, stares out ambiguously at us. As he explains, these complex, sometimes controversial symbols through animal masks “...conceal far more complex faces, that is, human ones.”

The human realities of Maus back through time are starkly visualised in MetaMaus, notably through two spreads of the Spiegelmans’ family tree. These resemble a comic, each life condensed into a name and dates inside one box connected to another, full of lives at the start of World War II but emptied out by the end to leave only thirteen survivors.

Nadja, Art, Dash & Françoise, 2004

Maus‘s impact forward in time are also revealed in candid interviews with Art’s wife, Françoise Mouly, and their two children, Nadja and Dash. While their photographs and those of others from Art’s family enrich MetaMaus, he shrewdly showed very few photos in his graphic novel, so that their intrusion forces us to question how documentary and ‘real’ any photo can be when compared to the precise compositions and levels of meanings distilled into Art’s deceptively naive cartooning.

For many, Maus was a revelation, the first graphic novel they had ever read. MetaMaus is equally revelatory, an author’s guided tour through the layers of thinking, practice, references and emotions behind his enigmatic mask.